Welcome to the world of Burmese Boxing, where tradition meets relentless combat in one of the world’s most brutal fighting arts – Lethwei. Join us as we explore the raw intensity and unyielding spirit that define this captivating discipline.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Lethwei, also known as Burmese Boxing or the ‘Art of 9 Limbs,’ is a form of kickboxing that originates from Myanmar (formerly Burma) in Southeast Asia. This full-contact combat martial art is widely recognized as one of the world’s most brutal fighting disciplines, with a history shrouded in secrecy for over a thousand years, characterised by bare-knuckle fights and minimal rules. This post aims to delve deep into the heart of Lethwei, unveiling its rich history, techniques, and cultural significance. Explore why Lethwei has garnered its formidable reputation in the world of martial arts, and is celebrated for its unmatched raw intensity and unwavering spirit.

Lethwei fighters wrap their hands in hemp or gauze, but they do not wear gloves, emphasizing the raw and unfiltered nature of the sport.

History

Martial arts traditions and fighting sports have always been an integral part of life in Burma. Lethwei is a fighting art that has been practised for centuries by the Burmese.

Myanmar (formerly Burma), the home of the brutal bare knuckle experience that is Lethwei.

Used as preparation for war in ancient times, it also served as a rite of passage for boys transitioning into adulthood. Lethwei is one of the four traditions of Thaing (Burmese martial arts). The others include Bando (unarmed self-defence), Banshay (armed self-defence), and Naban (grappling). Ancient Burmese armies successfully used the Burmese fighting arts in numerous wars and conflicts with neighbouring countries.

Ancient History

For more on the history of Lethwei. Click on the links below.

Within Myanmar culture, there is a widely held belief that Lethwei was developed by Burmese monks around the 3rd century, with the primary objectives of instilling discipline and providing self-defence skills. Ancient royal chronicles and inscriptions found on temple walls help support these claims. In particular, the inscriptions on temple walls at the ancient city of Bagan establish how Lethwei around was being practised around 800 A.D. Additionally, ancient royal chronicles and other records describe how Lethwei became increasingly popular during the 10th century A.D. It was during this period the warrior king, Anawratha, defeated the neighbouring tribes and founded the first Burmese Empire.

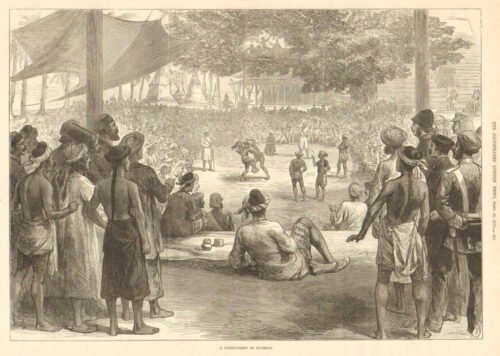

Later, between the 16th and 18th centuries, Lethwei spread to Myanmar’s neighbouring countries. This was through the conquests of the neighbouring kingdoms of Siam (Thailand) and Laos. It was around this time that Lethwei became the national sport of the empire. Tournaments were held during every festival and fighters were well rewarded for their victories. Indeed, from 1044 to 1885, highly skilled boxers were designated ‘Royal Boxers’. Participation was unrestricted, welcoming males of all social classes, from kings to peasants. Matches were held in sandpits, and boxers fought without protective gear, only wrapping their hands in hemp or gauze. The outcome of a fight was determined by knockout or when a participant could no longer continue. There were no draws.

The martial art has seen many ups and down when it comes to its practice, especially in the face of colonial rule. The practice of Lethwei continued for many centuries. However, it was made illegal under various foreign invading governments. First under the British during their occupation of Burma (1824-1948). Lethwei practice was suppressed since it was perceived as a potential threat to the British occupation. This prohibition continued under Japanese Imperial rule during WWII and under the military rule of the Burmese government post-war until 2011. During these periods, the practice of the art took place mainly in remote rural villages away from the watchful eyes of the ruling authorities.

After World War II, Burma was under military rule from 1961 to 2011. During this period, Lethwei managed to survive thanks to the dedicated efforts of native practitioners. Modern Lethwei was pioneered by Burmese Olympian boxers Kyar Ba Nyein and U Ba Than Gyi, who served as the Head of Physical Education for Burma. Their primary goal was to restore Lethwei as the national sport and integrate it into the physical education system. Starting in 1954, Kyar Ba Nyein initiated the process of drafting new rules and regulations to revitalise Lethwei, which had been in a state of disarray at the time. Nyein embarked on journeys across Myanmar, teaching the ancient sport to villagers. After months of training, these villagers were often encouraged to participate in competitive matches. It was Kyar Ba Nyein’s tireless efforts that laid the foundation for Lethwei’s development into the sport it is today. Unfortunately, the new military dictatorship proved to be unfavourable for the empowerment of its citizens. The practice of Lethwei remained in the shadows, confined to rural areas and specific holiday celebrations.

NB: Tattooed Men

Ancient Burmese boxers adorned their legs, arms, and bodies with intricate and meaningful designs and patterns through tattoos. Temple and royal fighters, in particular, would often bear tattoos on their chests, featuring animal motifs like tigers and cobras, as well as mythological figures such as ogres and dragons. Colourful tattoos on their legs were thought to bestow upon the boxers supernatural attributes like enhanced strength, durability, skill, and speed. The tradition of tattooing is not as prevalent in modern times.

Watercolour painting from 1897 depicting a 19th century boxing match in Burma. The fighters wear longyi and displaying Htoe Kwin tattoos.

Revival and Resurgence

For more on the history of Lethwei. Click on the links below.

Over the last 30 years, Lethwei has undergone modern restructuring and organisation, aiming to gain international recognition and appeal. This shift towards greater professionalism and organisation has led to improved safety standards, international competitions, and increased opportunities for Lethwei athletes to compete on a larger stage. The Myanmar Traditional Boxing Federation (MTBF) serves as the primary governing body for Lethwei worldwide. In 1996, during the Golden Belt Championship in Yangon, the MTBF introduced modern Lethwei rules. These changes were instrumental in making Lethwei more appealing and marketable on the global stage. The more recent adaptations of Lethwei are often referred to as “Myanmar Traditional Boxing.” This adapted form of Lethwei, known as ‘Myanmar Traditional Boxing,’ has transitioned from fighting in sandpits to fighting in boxing rings. These modifications also encompassed the introduction of weight classes and timed rounds.

Lethwei saw significant progress in 2011 when Myanmar’s military dictatorship ended, and the country opened up to the world, providing a platform for the sport to reach an international audience. This milestone led to the establishment of the World Lethwei Championship (WLC) and prompted further modifications to the rules to cater to a global audience, including the introduction of ringside judges and adjustments to traditional fight rules.

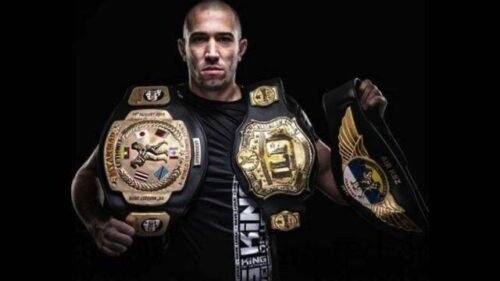

The inclusion of foreigners in the sport also contributed to its growing popularity. This surge in popularity reached new heights in 2016 when Lethwei welcomed its first non-Burmese World Lethwei Champion, the French Canadian David Leduc. After winning the belt, Leduc dedicated his life solely to Lethwei, becoming the spearhead in the sport’s international rise. In 2016, he was awarded a certificate of honour in recognition of his efforts as a fundamental part of Lethwei’s international expansion.

Overall, the efforts of Kyar Ba Nyein and others have played a significant role in preserving and modernising Lethwei, allowing it to gain recognition on the international stage.

NB: Sanctioning worldwide

Due to the violent nature and rules of the sport, Lethwei faces challenges in gaining sanctioning and is illegal in most countries outside of Myanmar. Headbutting is allowed in Lethwei, but is prohibited in most other martial arts, including Mixed Martial Arts (MMA), kickboxing and Muay Thai. As of 2022, Burmese boxing is only legal in the following countries: Myanmar, Japan, Singapore, Slovakia, Austria, Thailand, Taiwan, United Kingdom, United States (Wyoming only), New Zealand and Poland.

Beyond Rangoon - Burmese Boxing Today

For more on the history of Lethwei. Click on the links below.

Today, the nation formerly known as Burma is undergoing rapid change as it strides towards modernisation and full democracy. While Naypyidaw has taken over as the new political centre, Yangon (formerly Rangoon) remains the cultural heart of the nation. In Yangon, colonial-era buildings stand in harmony with majestic Burmese pagodas, creating a unique architectural landscape. Despite this splendour, the city’s spiritual richness stands in stark contrast to the pervasive poverty experienced by ordinary Burmese.

The prolonged political and economic turmoil in Myanmar has posed immense challenges for its people. Decades of military rule, political instability, and economic uncertainty have entrenched widespread poverty and severely limited opportunities. In this challenging environment, many Burmese men turn to Lethwei as a means of bettering their circumstances. Lethwei offers not only physical and mental discipline but also a chance to earn a livelihood through the sport. For some, it serves as a pathway to recognition, success, and a way to navigate Myanmar’s turbulent socio-economic landscape, offering a ray of hope amidst adversity. As of 2017, with the minimum monthly wage in Myanmar hovering around $70, even a 10-year-old can compete in Lethwei matches, earning between $30 and $100

While Lethwei’s roots are deeply embedded in Myanmar’s history and culture, the sport began to gain international recognition. Organisations such as the World Lethwei Championship (WLC), Marshall Fighting Championship (MFC), and Sparta Sports and Entertainment (USA) were instrumental in promoting the sport beyond Myanmar’s borders. These efforts sparked growing interest among fighters, trainers, and spectators worldwide.

ONE Championship, a powerhouse promotion in Southeast Asian martial arts, hosted its inaugural Lethwei match in Yangon, Myanmar, in 2015, featuring Burmese martial artists Phian Twei and So Tet Oo. Subsequently, in 2016, Myanmar launched its first international promotion, the World Lethwei Championship (WLC), showcasing modern Lethwei rules. In 2017, ONE Championship and WLC established a partnership to share athletes. Since then, Lethwei has enjoyed increasing international recognition. Regular matches continue to draw significant crowds at Aung San and Thuwanna Stadiums in Yangon.

In 2021, Myanmar underwent a significant upheaval marked by a coup d’état (overthrow of the government) on February 1st. During this time, the country’s military (known as the Tatmadaw) seized control from the civilian government led by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD). Citing alleged election fraud in the November 2020 general elections as justification, this power shift has plunged the nation into political turmoil, profoundly affecting governance, stability, and its future trajectory. These developments have reverberated across various sectors, including sports and cultural activities like Lethwei. Following the coup, Zay Thiha, the founder and chairman of the WLC, was arrested, and it appears that the World Lethwei Championship has ceased operations. After emerging from obscurity, Lethwei now faces the threat of being forced back underground amidst the current political climate.

ONE Championship has played a pivotal role in promoting Southeast Asian martial arts, including Lethwei, by providing a global platform for athletes to showcase their skills and traditions, thus elevating the visibility and appreciation of these rich cultural disciplines worldwide.

Characteristics of Burmese Boxing

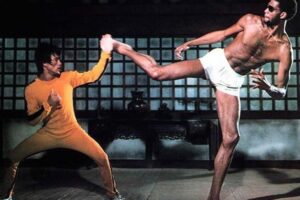

Lethwei’s fighting techniques encompass punching, elbowing, kneeing, and kicking. The art also incorporates grappling methods, including clinching, throwing, choking, and trapping. In this regard, Lethwei shares similarities with other martial arts found in neighbouring Asian regions. Examples include Muay Thai (Thailand), Pradal Serey (Cambodia), Muay Lao (Laos), Tomoi (Malaysia), and Musti-yuddha (India). These similarities primarily manifest in the execution of strikes, roundhouse kicks, clinches, elbows, and knee strikes.

Traditional Lethwei, with its use of bare knuckles and elbows, embodies a raw and unfiltered approach to combat, emphasizing the brutal effectiveness of striking techniques in close-quarters combat.

However, Lethwei stands out as the sole Southeast Asian boxing discipline still contested with bare fists, as neighbouring countries’ systems have all embraced the use of gloves in competition. In Lethwei, the absence of gloves affords a broader spectrum of striking techniques using the hands. Bare-fist punches demand a higher degree of skill and precision compared to when wearing gloves, primarily owing to the increased risk of injury to the bare hands. Consequently, Lethwei fighters must exercise particular caution to safeguard their hands during competitions and training in order to mitigate the risk of injury.

The Art of 9 Limbs

Muay Thai from neighbouring Thailand is often referred to as the “Art of 8 Limbs.” Lethwei, on the other hand, earns its nickname as the “Art of 9 Limbs” due to its distinctive incorporation of headbutts in its techniques. The inclusion of headbutts enhances the unique and practical nature of Lethwei, making it stand out among striking arts. Headbutting serves as an effective means of both attack and counterattack, particularly in close-quarters clinching or grappling situations. Surprisingly, the head is also utilised defensively to counter incoming punches. The thickness of the cranial bones potentially inflicts significant damage to an opponent’s fist or wrist bones.

Popular headbutting techniques:

- Hkaung tike: Used during the clinch.

- Hkaung sount tike: a rushing headbutt.

- Hkun hkaung tike: a flying headbutt technique.

Headbutts are a distinctive feature of Lethwei, allowing fighters to utilize their heads as formidable weapons during combat, adding a unique and aggressive dimension to the sport’s fighting style.

The wide range of techniques at the disposal of a Lethwei fighter enables them to inflict significant damage on an opponent. However, it also exposes the fighter to a higher risk of receiving reciprocal harm. This heightened danger becomes particularly apparent when juxtaposed with other kickboxing traditions characterised by much stricter rules.

No Rules

In Lethwei, there are minimal rules and restrictions. However, certain actions such as hair-pulling, slapping, biting, eye-gouging, and striking the genitals are strictly prohibited. The rules governing knocked-down fighters are straightforward: when one fighter is down, the standing opponent is not allowed to continue striking their fallen adversary. Nevertheless, if both fighters go down simultaneously, the use of elbows, knees, or headbutts is prohibited while on the canvas of the ring.

Friendly Fire

The fights are unique in that, although brutal, the spirit is more about celebration than violence. Lethwei celebrates the competitive spirit, manhood, and pride rather than mere winning and glory-seeking. As intense as Lethwei fights can be, most of the aggression is typically confined to the actual bout. However, this same aggression remains inside the ring even after the match concludes. Lethwei fighters have a primary goal of winning the fight and typically avoid causing permanent harm to their opponents. In an average Lethwei match, it is not uncommon to witness one fighter extending a helping hand to their knocked-down opponent. Furthermore many fighters will demonstrate concern by checking on a downed adversary’s well-being.

Additionally, in contrast to sports like Mixed Martial Arts or boxing, Lethwei lacks the same level of arrogance or attitude, with minimal trash-talking. Respect and courtesy are consistently present, fostering a sense of brotherly respect among all fighters.

Traditional and Modern Boxing

In the 20th century, as Lethwei gained popularity, there was a need to make it appealing to people worldwide. This led to two different types of Lethwei, ‘Traditional’ and ‘Modern’.

Traditional Lethwei sticks to its roots with bare-knuckle fights and few rules, keeping the sport’s original toughness. On the other hand, Modern Lethwei added safety measures and organised rounds to make it more acceptable globally. In this exploration, we’ll look at the key differences between these two versions of Lethwei and understand their special traits, rules, and how they connect with Myanmar’s rich culture.

Traditional Lethwei (left), rooted in ancient Burmese culture, emphasizes raw aggression and minimal rules, often fought in sandpits with no protective gear. In contrast, modern Lethwei (right) incorporates standardized rules, organized competitions, and sometimes takes place in regulated rings, reflecting efforts to adapt the sport for broader international appeal while preserving its core essence.

Traditional rules

Traditional Lethwei, fought in Myanmar’s villages, is a raw and unstructured form of this martial art, deeply rooted in local culture. It involves spontaneous, bare-knuckle fights with minimal rules, often centred around defending village pride. These matches symbolise tradition and resilience in rural Myanmar, preserving their heritage and identity.

Traditional fights differ greatly from the commercial Lethwei shows and spectacles held in major cities like Yangon and Mandalay. For the people of Myanmar, Lethwei is not merely a combat sport or fighting art; it is an integral part of their national identity, tradition, and culture. Traditional Lethwei matches are typically organised during festivals, religious ceremonies, and cultural celebrations. Myanmar’s calendar features various annual festivals, with the most famous being Thingyan, a four-day celebration (April 13-16) that reaches its peak on New Year’s Day (around 17th/18th April). Lethwei contests are also a part of local ‘pagoda’ festivals, funerals, and community celebrations. Lethwei tournaments have been an integral part of these festivals for centuries, contributing significantly to their essence.

In rural areas, traditional Lethwei remains deeply ingrained in community life, serving as a testament to Burmese heritage and resilience, with matches often doubling as communal gatherings where skills are honed and local pride is on display.

For more on traditional Lethwei. Click on the links below.

The traditional festival fights are a cause for great celebration in local villages, and many people from the community gather to cheer for the local fighters. Many practitioners of Lethwei are farmers and labourers who participate in the sport during their leisure time. In smaller villages, Lethwei traditions persist as a vital aspect of the spiritual and physical development of young individuals.

The traditional fights are often held outdoors in traditional circular sandpits although some may have modern boxing rings. The matches necessitate the presence of two officials or referees, with one assigned to each boxer, responsible for enforcing the rules of the fight. These referees intervene to separate the boxers when they engage in clashes, throwing, or tripping techniques. Additionally, there may be a chief referee, who acts as an arbiter, stepping in to resolve any issues that may arise. Traditional Lethwei adheres to the general rules stated above (5 x 3 minutes rounds/2 minute rest between rounds/rules for victory etc). However, it may incorporate its own localised variations.

The traditional rules are known as ‘yoe yar rules’ (from the Burmese ‘Myanma yoe yar Latway’, translation ‘Myanmar traditional boxing’). Traditional Lethwei is notorious for not having a scoring system and for its controversial rule of knock-out only to win. At the end of the match, in the eventuality that there is no knockout or stoppage, if the two fighters are still standing, even if one fighter dominated the fight, the match is declared a draw. Fighters can win by incapacitating their rivals in a few different ways.

- Permitted techniques – Headbutts, punches, elbow strikes, knee strikes, kicks, clinchwork, sweeps, throws and takedowns.

- Three-Five x 3 minute rounds.

- 2 x minutes rest in-between rounds

- The only way to win in Lethwei is by knockout, or if a fighter is unable to continue. There is no point system.

- If both fighters are standing at the end of the fifth round, it is declared a draw

- A knock-out (KO) is when a fighter falls to the ground, leans unconscious or if a fighter is unable to stand up or defend themself for 20 seconds.

- When 3 knockdowns are performed in a single round, the fight is terminated and scored as a Technical knock-out (TKO).

- When a fighter is knocked down 4 times during a fight, the match is terminated and scored as a TKO.

- A TKO can also occur when a fighter forfeits, has an injury or is in a position that can damage or severely harm them if the fight continues. The ring doctor is consulted and makes the decision.

- Special Rest/Second chance rule.

Unique to Lethwei is the allowance known as the ‘special rest,’ which can be used only once during a fight. This rule provides a second chance to a downed fighter. If one of the fighters is knocked out, their corner is granted a two-minute window to revive the fighter, offering them an opportunity to continue the match. This component comes from ancient grudge matches and high stakes fights where money and pride were on the line. It gives the fighter one last chance to get back into the fight after being floored. While this may appear excessive to outsiders based on what is now known about concussion and deaths post fights in combat sports. However, the Burmese traditionalists view it as a crucial lifeline, giving a fighter a much-needed second chance after being knocked out. This component was once allowed in other Southeast Asian versions of kickboxing but has slowly been eliminated. Only Traditional Lethwei continues this tradition.

- Most Lethwei promotions in Myanmar.

- Annual Myanmar Lethwei World Championship.

- Air KBZ Aung Lan Championship.

- International Lethwei Federation Japan.

- Local and regional festivals & celebrations.

Modern Boxing

Modern Lethwei, in contrast to traditional village Lethwei, is a more organised and regulated form of the martial art. It incorporates rules, safety measures, and structured competitions, attracting a wider audience. While still retaining its cultural roots, modern Lethwei promotes professionalism, with fighters signing contracts, competing for titles, and adhering to safety protocols.

Modern Lethwei, is the organised and regulated version of Lethwei practised in a more controlled and structured environment, often for sport and entertainment purposes. This differs from traditional rural Lethwei matches, which are often less formal and can be more spontaneous and rough. Modern Lethwei follows a set of rules and regulations established by governing bodies and promotions, such as the World Lethwei Championship (WLC). These rules are designed to ensure the safety of the fighters and to make the sport more palatable for a wider audience.

For more on Modern Lethwei. Click on the links below.

Safety measures in Modern Lethwei include pre-fight medical check-ups, the presence of referees, and medical personnel on-site. Fighters in organised Lethwei events may also be required to wear gloves, mouthguards, and sometimes even protective headgear. Modern Lethwei is typically promoted as a spectator sport, with organised events held in arenas or stadiums. These events are often ticketed and can be watched by a live audience as well as through television or online broadcasts.

Fighters in Modern Lethwei tend to undergo more formal training and conditioning programs to prepare for their matches. They may be part of gyms and training camps that provide coaching and facilities. In contrast, traditional rural Lethwei fighters often come from local backgrounds and may have a more unstructured training regimen. Furthermore, Modern Lethwei promotes a level of professionalism, with fighters signing contracts, receiving purses, and competing for titles and rankings within organisations. Traditional Lethwei matches are often more about local pride and honour, and fighters may participate on an ad-hoc basis without formal contracts or rankings. Both forms of Lethwei have their own unique characteristics and appeal to different audiences.

Several fighters have risen to prominence in the world of Lethwei, earning recognition for their skill, toughness, and achievements in the sport. Dave Leduc, known as the “King of Lethwei,” has achieved significant success, winning multiple Lethwei world titles and popularising the sport internationally. Tun Tun Min, a Burmese fighter, is renowned for his powerful striking and aggressive style, while Too Too has impressed with his tenacity in the ring. Saw Ba Oo, another formidable competitor from Myanmar, has earned a reputation for his impressive performances, while Soe Lin Oo is a rising star known for his technical skills and determination. These fighters, among others, have contributed to the growing popularity of Lethwei both in Myanmar and around the world.

With the modern version of Lethwei, several rules were changed by various organisations in a bid to improve safety and also provide clear winners in Lethwei bouts. In 1996, the Myanmar Traditional Lethwei Federation created the tournament ruleset for the inaugural Golden Belt Championship tournament. The two-minute special rest timeout was removed and judges were added ringside to determine a winner in the event of no knockout. This modified ruleset prevented the outcome of a draw and helped choose a winner to advance in the tournament. Myanmar’s first international promotion, the World Lethwei Championship (WLC), also opted for this ruleset in order to follow international safety regulations and have clear winners.

- Permitted techniques – Headbutts, punches, elbow strikes, knee strikes, kicks, clinchwork, sweeps, throws and takedowns.

- Three-Five x 3 minute rounds.

- 2 x minutes rest in-between rounds.

- One referee oversees the fight, with three judges scoring.

- A knock-out (KO) is when a fighter falls to the ground, leans unconscious or if a fighter is unable to stand up or defend themself for 20 seconds.

- When 3 knockdowns are performed in a single round, the fight is terminated and scored as a Technical knock-out (TKO).

- When a fighter is knocked down 4 times during a fight, the match is terminated and scored as a TKO.

- A TKO can also occur when a fighter forfeits, has an injury or is in a position that can damage or severely harm them if the fight continues. The ring doctor is consulted and makes the decision.

- No special rest option.

- Judging criteria – A knockout is still highly desired under this ruleset, but in the event that a bout goes the distance, judges will present a decision. The 3 judges should score the bout based on – aggression, damage, amount of blood drawn and number of significant strikes per round.

Several promotions have adopted modern Lethwei rules to showcase the sport to a broader audience and attract international talent. Some of the prominent promotions that feature modern Lethwei rules include:

- World Lethwei Championship (WLC): WLC is one of the leading organisations dedicated to promoting Lethwei on a global scale. They host professional Lethwei events featuring fighters from around the world, with modern rules aimed at ensuring fighter safety while maintaining the essence of the sport.

- ONE Championship: While primarily known for mixed martial arts (MMA), ONE Championship has also ventured into Lethwei by featuring bouts under modern rules. They have hosted Lethwei matches as part of their events in Myanmar and occasionally showcase Lethwei fighters on their international cards.

- Burmese Lethwei Federation: The Burmese Lethwei Federation organises events within Myanmar that adhere to modern Lethwei rules. These events serve as platforms for local and international fighters to compete and showcase their skills under standardised regulations.

- Golden Belt Championship: The Golden Belt Championship is a prestigious Lethwei event held in Myanmar, featuring top fighters competing under modern rules. It attracts both local talent and international competitors, contributing to the growth and popularity of modern Lethwei.

Canadian Dave Leduc (the ‘King of Lethwei) is a pioneering figure in Burmese boxing. Becoming the first non-Burmese World Lethwei Champion and playing a pivotal role in its international recognition and growth

The Golden Belt

In the realm of Modern Lethwei, two prestigious titles stand out: the “Golden Belt” and the “Golden Belt Championship.” While both embody excellence in the sport, they differ in terms of prestige and recognition. In this exploration, we’ll delve into the distinct characteristics of these two titles, shedding light on what sets them apart and the significance they hold in the world of Burmese bare-knuckle boxing.

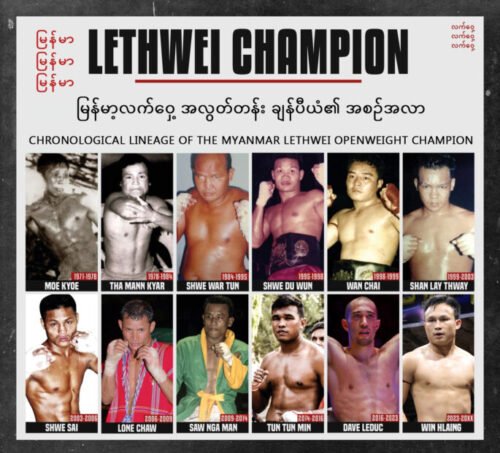

Golden Belt

The title of Myanmar Lethwei Champion, also known as the “Golden Belt,” holds significant prestige within the Lethwei community. Contrary to its name, the Golden Belt is not a physical belt but an honorary title bestowed upon the top fighter in each weight category. It is considered the highest accolade for Lethwei fighters, with the openweight class champion regarded as the strongest fighter in Myanmar, akin to a pound-for-pound champion in the world of Lethwei. Winning a Golden Belt symbolises a fighter’s excellence and achievements within the sport, marking them as a true champion.

This coveted title can be earned in various Lethwei promotions or events, as it is not tied to a specific organisation. As a symbolic honour, champions often put their titles on the line when competing in other promotions. The Golden Belt can only be passed down through decisive victories, such as by knockout, technical knockout, forfeit, or due to a clear violation of conduct. In cases where the title becomes vacant, either due to the champion vacating it, being stripped for inactivity, or an inability to defend it, the top contenders must vie for the belt. However, to crown a champion, a fight ending in a draw is not an option; a clear winner must be determined, even if a knockout is not achieved.

The Myanmar Lethwei Openweight Champion or the “Golden Belt” is actually not a belt. It’s an honorary title and symbolic status given to the top fighter. It is the highest honour and most prestigious title in Lethwei.

Golden Belt Championship

On the other hand, the “Golden Belt Championship” is an event or tournament organised by a specific Lethwei promotion. For example, the World Lethwei Championship (WLC), which is one of the prominent Lethwei organisations. This championship serves as a platform for fighters to compete for the coveted Golden Belt title within that particular promotion. Fighters participate in a series of matches or a tournament format, with the winner being awarded the Golden Belt championship title specific to that promotion. Different Lethwei promotions may have their own Golden Belt Championships.

The ‘other Golden Belt’ the inaugural championship belts offered at the WLC Championships each year. Held at the Thein Pyu Stadium annually where young, aspiring fighters can compete under tournament rules.

The two-minute injury timeout was abolished in these tournaments and a judge was added at ringside to determine the winner in the event of no knockouts. This modified ruleset prevented a draw outcome and helped select the winner to advance to the tournament. Myanmar’s first international promotion, the World Lethway Championships, has chosen this set of rules to follow international safety regulations and determine a clear winner. Judging criteria Knockouts are still strongly desired in the ruleset, but the judges will make the call if the match goes on too long.

Culture and Ceremony

Like Muay Thai, traditional Lethwei is steeped in vibrant and charismatic traditions. One of these traditions, the opening ceremony, takes place at the beginning of a Lethwei match. The opening ceremony is conducted in accordance with traditional customs to foster a favourable outcome for the fighters.

Lethwei Yay, the traditional pre-fight dance in Lethwei, serves as both a ritualistic display of respect and a means to mentally prepare fighters for battle, embodying the spirit and tradition of Burmese martial arts.

For more on the culture of Lethwei. Click on the links below.

Before each bout, competitors perform a traditional warrior dance known as the Lethwei Yay accompanied by the tempo of a traditional orchestra. The Lethwei Yay serves as a, serving as a formal challenge to the opponent. It is also a means to showcase the fighter’s skill and courage while paying homage to Buddha. This dance is reenacted at the end of the fight by the victorious fighter. The dance is akin to the ‘Wai Kru Ram Muay,’ a dance practised by Muay Thai fighters in neighbouring Thailand.

The Lekkha Moun is a traditional gesture performed by Lethwei fighters to challenge their opponents with courage and respect. It is done at the beginning of the lethwei yay and can also be done while fighting. During a Lethwei match, a fighter may perform the Lekkha Moun to taunt their opponent to be more aggressive. The lekkha moun is done by bending the left arm across the upper torso. The right palm then is clapped 3 times with the right palm to the crook of the elbow of the left arm. The clapping hand must be cupped, while the left hand must be placed under the right armpit.

Lethwei contests are accompanied by the enchanting sounds of traditional Myanmar music, skillfully performed by an ensemble known as the ‘Saing Waing.’ This captivating music ensemble consists of resonant drums, melodious cymbals, and rhythmic bamboo clappers. The melodious tunes echo throughout the event, starting with the opening ceremony and continuing through the rituals and the entire tournament. The music’s volume and tempo are orchestrated to harmonise with the ebb and flow of the fights. As the match commences, the tempo of the music gradually intensifies, reaching a frenzied climax during the dynamic clashes and exchanges between the fighters.

Ring attire in Lethwei is straightforward yet significant. Fighters rely solely on hemp or gauze cloth to wrap their hands, providing minimal protection that can lead to severe cuts for both combatants. Typically barefoot, with occasional anklets, fighters eschew loose boxing trunks in favour of simple, dark-coloured shorts. To aid spectators in distinguishing between opponents, especially amidst the chaos of the bouts, fighters may also don a small ‘longyi,’ a sarong-like garment, folded into a triangular shape and worn around the waist. This attire not only serves practical purposes but also adds to the traditional and distinct flavour of Lethwei competitions.

In Lethwei matches, traditional Burmese music, often featuring drums, gongs, and flutes, accompanies the fighters, adding to the atmosphere and intensity of the bouts.

Training in Burmese Boxing

Lethwei training is characterized by rigorous physical conditioning and mental discipline, preparing fighters to endure the intense demands of the sport’s raw and unyielding combat.

Lethwei training in Myanmar encompasses both professional and traditional approaches, with fighters honing their skills in specialized training camps scattered across the country. These camps serve as crucibles for developing the physical prowess, technical expertise, and mental fortitude required to excel in the sport. Whether in modern facilities or traditional settings, Lethwei practitioners undergo rigorous training regimens tailored to cultivate their striking abilities, endurance, and fighting spirit.

For more on the training in Lethwei. Click on the links below.

Lethwei training conditioning is incredibly gruelling due to the high physical demands of the sport. Most of the training takes place outdoors in open-air makeshift training camps, although fighters can even be found training in narrow alleyways amidst living areas. Training stations are rotated through for the warm-up before engaging in multiple sparring matches to refine technical skills. Many camps make use of cost-effective and dependable resources such as sandbags and tires as training aids.

Lethwei fighters need to be conditioned to deal with the extreme punishment inside the ring. They spend a lot of time conditioning their limbs to make them stronger and more effective for dealing out and absorbing damage. To aid with this, punching boards (also known as Makiwara in Japanese martial arts circles) are employed to toughen the knuckles, elbows, knees, and feet. Other stations may involve activities like bouncing on tires, shifting stances for stamina and balance, shadowboxing, and heavy bag work for power training.

Lethwei fighters stand out as some of the most technically skilled strikers worldwide, boasting exceptional proficiency in handwork and footwork. Their ability to hold their own against top boxers and kickboxers is a testament to their training regimen. This includes extensive sparring drills, padwork, bagwork, shadowboxing, and a meticulous focus on technique.

In addition to technical prowess, Lethwei fighters prioritise cardiovascular fitness to withstand the gruelling pace of bouts. Endurance is crucial for enduring the relentless action and intense pressure to secure victory within the short rounds. To achieve peak cardio levels, fighters engage in rigorous sparring, bagwork, shadowboxing, and running sessions, ensuring they are prepared for the demands of competition.

Ultimately, each camp is unique, but most incorporate a combination of these training styles and equipment.

In Myanmar, Lethwei fighters often train with improvised or makeshift equipment due to economic challenges, demonstrating their dedication and resourcefulness in pursuit of their craft.

Professional Fight Camps in Yangon

Professional fight camps in Yangon have attracted an increasing number of foreigners each year. Thut Ti, an established gym managed by renowned fighter Lone Chaw and original owner Win Zin Oo, boasts a modest setup with a small stable of fighters. Despite its basic facilities, Thut Ti attracts foreigners seeking an authentic Lethwei training experience. On the other hand, newer camps like Phoenix Myanmar Lethwei Gym offer modern amenities similar to those found in Bangkok. With its comfortable indoor training environment, Phoenix appeals to many foreigners. Promoters hope that Lethwei in Yangon will mirror the popularity and success of Muay Thai training camps in Thailand’s capital Bangkok.

NB: In popular culture

Burmese Boxing has been featured in media such as film, television, comics and anime. Dave Leduc's defeat of Tan Tan Minh in 2016 brought the sport to global attention. Lethwei was featured by Leduc as a guest on The Joe Rogan Experience podcast by Joe Rogan. In 2018, Frank Grillo travelled to Myanmar to feature Lethwei in the Netflix documentary Fightworld. Burmese art is also featured in the popular Japanese manga series 'Kengan Ashura'. In this series, a Burmese Lethway master named Saw Payne is so immortal that he shatters all the bones in his hands when an opponent tries to hit him.

Dave Leduc – Featuring on the Joe Rogan podcast (left). Frank Grillo’s Netflix series ‘Fightworld‘ sees him visit Myanmar to explore the world of Lethwei (right).

Video - Training in Myanmar

0:16

Lethwei for Self Defence

Renowned globally for its street effectiveness and brutal efficiency, Lethwei is widely regarded as a highly effective form of personal combat. Originally developed for battle rather than sport, it has been used in Southeast Asia for centuries. Lethwei’s principles align closely with street-fighting applications, prioritising directness, pragmatism, and sheer aggression. Beyond mere victory, its focus extends to survival and resilience, reflecting its historical roots in combat rather than sport. The discipline’s rigorous training regime and emphasis on direct violence make its techniques formidable for extreme defence. Executed with pinpoint accuracy and extreme force, punches, kicks, and headbutts in Lethwei can swiftly incapacitate even the most resilient adversaries.

For more on the street effectiveness of Lethwei. Click on the links below.

The training regimen in Lethwei is rigorous and holistic, encompassing not only timing, distance, and movement but also the capacity to endure and deliver punishment. Fighters dedicate significant time to conditioning their bodies to withstand impact while honing their offensive arsenal. This comprehensive approach, coupled with Lethwei’s unrestricted rules, underscores its applicability in real-world self-defence scenarios.

Moreover, Lethwei offers a versatile toolkit that surpasses many conventional kickboxing and martial arts methods. Its emphasis on bare-fist strikes, head-butting, trapping, clinching, and throwing renders it exceptionally potent for personal defence. Beyond physical prowess, Lethwei instils invaluable life lessons, fostering a culture of resilience, discipline, and adaptability. Ultimately, Lethwei training equips practitioners not only to navigate the challenges of combat but also to confront life’s adversities with courage and efficacy.

Lethwei fighters approach combat with a distinct mindset compared to boxing or kickboxing. Their focus is solely on securing a knockout, as it’s the only path to victory in their sport, unlike scoring points. Additionally, their expertise in bare-knuckle fighting translates seamlessly to real-life street fighting scenarios, where there are no rules or gloves to cushion the impact. Unlike boxers and Muay Thai practitioners who rely heavily on larger gloves for defence, Lethwei fighters utilise superior head movement to evade strikes, making their techniques more adaptable to the unpredictability of street fights. This familiarity with bare-knuckle combat positions Lethwei fighters as formidable contenders in street fighting, offering a striking style that rivals, if not surpasses, traditional boxing and Muay Thai in real-world self-defence situations.

While Lethwei possesses certain strengths as a form of self-defence, it also has notable limitations and areas where it may not be the most practical option. Lethwei’s focus on stand-up fighting neglects grappling, ground fighting, and self-defence against weapons. Furthermore, the sport may not provide comprehensive training in defensive manoeuvres, increasing vulnerability in real-world self-defence situations. The aggressive nature of Lethwei techniques also raises the risk of injury during training and matches, potentially limiting its suitability for individuals seeking self-defence methods with lower risk. Accessibility and availability of traditional Lethwei training may also pose challenges for individuals seeking to learn self-defence. Overall, while Lethwei offers strengths in striking techniques and mental toughness, it also has limitations in defensive training, injury risk, and accessibility that individuals should consider when evaluating it as a self-defence option.

Pros:

- Effective striking techniques.

- Rigorous physical conditioning.

- Lethwei training instils mental toughness and discipline.

- Formidable in close combat situations.

- Enables practitioners to remain calm and focused in confrontations.

Cons:

- Neglects grappling, ground fighting, and self-defence against weapons.

- Defensive manoeuvres not as other fighting systems.

- Risk of injury during training and matches.

Conclusion

Lethwei’s ascent from its ancient origins to the contemporary sports arena underscores its enduring appeal and relevance. Its minimalist approach to combat, rooted in centuries of tradition, distinguishes it as a unique and captivating martial art. As it gains traction beyond its native Myanmar, it’s imperative to safeguard its cultural heritage while embracing its evolution on the global stage.

As of now, the future of Lethwei remains uncertain in the wake of the recent coup d’etat, which has led to the arrest of key figures such as WLC chairman Zay Thiha and the suspension of WLC operations. The political instability in Myanmar has cast a shadow over the sport’s trajectory, with concerns about the impact on its development, promotion, and international recognition. Amidst these challenges, Lethwei enthusiasts and practitioners hope for a resolution that will safeguard the sport’s heritage and ensure its continued growth on both national and global stages.

If you have enjoyed this post please share or feel free to comment below 🙂

Related Posts

Our Other Posts

Calculating Your Energy Needs Made Simple

For weight management, getting your energy needs right doesn’t have to require Einstein-level calculations. Keep