Discover how martial combat evolved from the Renaissance to Early Modern era, as duelling culture, battlefield tactics, and refined weapon arts shaped warriors across Europe and beyond.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The 15th to 18th centuries ushered in a profound transformation in warfare. The thunder of gunpowder drowned out the clash of swords, and the age of knights gave way to disciplined infantry, naval warfare, and formalised duelling. Across Europe and Asia, the rise of muskets, rapiers, and standing armies forced martial traditions to evolve—or vanish.

This era was one of both destruction and refinement. Swordsmanship evolved from raw battlefield violence into the refined discipline of fencing schools. Military strategy was formalised, training manuals emerged, and combat instruction shifted from noble elites to career soldiers. Meanwhile, global trade and colonial expansion fused fighting systems across continents, merging local traditions with European weapons and tactics. In this post, we explore how tradition and innovation collided to forge the foundations of modern martial and military systems.

European Renaissance 💡📜🧠🏛️

As Europe embraced science, philosophy, and reason, so too did its approach to combat evolve. The sword was no longer just a tool of bloodshed—it became a symbol of intellect, precision, and control. Martial skill was reimagined through geometry, logic, and discipline, transforming personal violence into something codified, elegant, and deliberate. In this era, fighting became thinking.

Click on the links below to read more.

⚔️📚🧠 Martial Refinement in the Age of Reason

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, Europe underwent a profound transformation in thought. The Renaissance revived classical knowledge and prioritised human potential, artistry, and scientific observation. This period sparked a rebirth in European martial traditions, blending science and combat. Fencing schools emerged, where swordplay became a refined practice of precision, honour, and tactical brilliance.

Later, the Enlightenment championed reason, empirical analysis, and intellectual discipline. Fencing evolved into a scientific discipline, with geometric principles governing every thrust and parry. These philosophical shifts reshaped how Europeans thought about violence, honour, and martial skill. The sword became more than a weapon; it became a symbol of status, intellect, and moral refinement.

🗡️📖 The Renaissance: Martial Skill as Art and Discipline

The Renaissance redefined personal combat by fusing classical ideals with evolving battlefield realities. As full plate armour faded and firearms reshaped warfare, the sword transitioned from a tool of war to a mark of personal skill and social identity. Fencing masters embraced geometry, timing, and form, teaching refined techniques grounded in both tradition and innovation.

This period also saw the rise of fencing schools, where noblemen and officers honed their craft as a form of self-discipline and cultural polish. Combat shifted from chaos to craft—measured, practiced, and intellectually engaged—laying the foundation for Europe’s codified martial traditions.

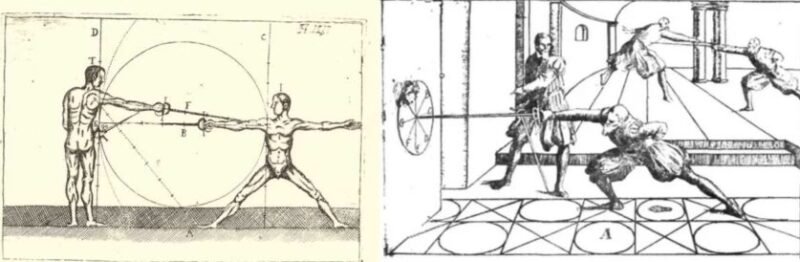

📐 The Rise of Systemized Swordsmanship

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, European martial traditions evolved as plate armour became obsolete and gunpowder warfare reshaped battlefield priorities. Swords transitioned from battlefield weapons to duelling and civilian self-defence, leading to fencing schools that trained both nobles and military officers. Italian masters like Salvatore Fabris, Ridolfo Capo Ferro, and Camillo Agrippa codified precise rapier techniques, refining footwork, thrusting mechanics, and defensive principles that would later influence military sabre training.

As duelling became intertwined with honour and legal disputes, many European nobles and military officers sought formal instruction. These contests were not just tests of skill but also demonstrations of status and refinement.

🇩🇪🤺📜 German Fencing Traditions & Kampfringen

Meanwhile, Germany’s martial traditions—particularly those codified in Johannes Liechtenauer’s Fechtbuch—preserved longsword techniques and armoured grappling (Kampfringen). Unlike the thrust-heavy Italian and geometric Spanish systems, German Fechtbücher emphasized control through binding, leverage, and half-swording techniques.

Kampfringen integrated grappling and dagger work, ensuring that fighters could dominate even in close-quarters combat. While the broadsword and buckler remained relevant, they gradually gave way to lighter dueling weapons. However, in regions like Scotland and Germany, backswords and basket-hilted broadswords remained essential for military close combat.

🇪🇸 🤺📜 Spanish Destreza and the Science of Fencing

In Spain, La Verdadera Destreza (“The True Art” of fencing) applied geometric principles, timing, and angular movement, reflecting the Renaissance’s scientific mindset. Unlike Italian rapier fencing, which prioritized direct thrusts and linear attacks, Destreza focused on circular footwork, strategic positioning, and mathematical precision to outmaneuver opponents efficiently.

Destreza’s emphasis on calculated precision made it particularly effective in prolonged engagements, contrasting with the fast-paced, thrust-heavy Italian rapier style. This methodology later influenced Spanish colonial fencing, as seen in adaptations within the Philippines and South America.

Cross-influences between Italian, German, and Spanish schools enriched European martial traditions, spreading advanced techniques across the continent. These developments transformed swordsmanship from brute force to calculated precision, shaping European martial arts, aristocratic culture, and duelling etiquette for centuries.

💡📜🤺🧐 The Enlightenment and the Evolution of Fencing

By the 17th and 18th centuries, the Enlightenment further transformed fencing into a systematised and scientific art. Masters broke down swordplay into biomechanical movements, governed by principles of logic and efficiency. The focus shifted to rational precision, calculated movement, and efficient decision-making—mirroring Enlightenment ideals of logic and discipline.

Weapons like the smallsword reflected this change—light, elegant, and designed for regulated duels rather than battlefield carnage. Duelling became a ritual of honour, embedded in legal and social codes. To fence well was not merely to fight—it was to demonstrate virtue, restraint, and cultivated excellence. Fencing had evolved from survival to symbol: a mental and physical discipline for the modern European gentleman.

🔫💥 The Birth of Battlefield Combatives in the Gunpowder Age

As European powers expanded aggressively across continents, their militaries were forced to adapt to the brutal realities of early gunpowder warfare. The introduction of the musket and arquebus reshaped tactics, but it did not end close combat—in fact, it made it even more essential. Slow reload times and clouds of blinding smoke often reduced battles to chaotic melees, where formations collapsed and survival hinged on the blade.

Infantry tactics evolved to meet this harsh reality. Soldiers drilled relentlessly in pike-and-shot formations, learning to fire controlled volleys before fixing bayonets or closing ranks with pikes to repel attackers. The bayonet, still in its early form, transformed muskets into improvised spears when the lines tightened. European armies placed growing emphasis on physical conditioning and hand-to-hand proficiency, knowing that once the smoke settled, the fight would be settled man to man.

These brutal encounters on the battlefields of Europe became the proving grounds for a new style of combat: drilled, aggressive, and instinctive. As colonial expansion carried European forces across oceans, these close-combat tactics travelled with them, laying the foundations for the refined, codified battlefield systems that would define the imperial wars of the centuries to come.

Renaissance swordsmanship schools in Europe emphasised precision, timing, and geometry—treating each strike, parry, and step as a calculated movement rooted in science and discipline.

Ottoman Empire ☪️ 🕌⚔️🌍

From the 14th to 17th centuries, the Ottoman Empire stood as one of the world’s most formidable powers, controlling vast territory across southeastern Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa. Their military dominance was no accident—it stemmed from a unique fusion of discipline, innovation, and strategic adaptability. With a mastery of siege warfare, combined arms tactics, and psychological intimidation, the Ottomans redefined how empires waged war. At the core of this machine stood the Janissary Corps—an elite standing army whose rigorous training and unwavering loyalty became the backbone of Ottoman military supremacy.

Janissary Training ☪️🛡️⚔️📜🏹

Click on the links below to read more.

👦🏽 🎯📜 The Devshirme System and Military Discipline

The Janissary Corps was one of the world’s first standing professional armies, pioneering the integration of firearms with archery and melee combat. Unlike feudal levies, Janissaries operated as a permanent military force, bound by rigorous discipline, strict hierarchy, and unwavering loyalty to the sultan.

At the heart of their recruitment was the devshirme system, which conscripted Christian boys from the Balkans, converting them to Islam and training them intensively in musketry, swordsmanship, and battlefield tactics. The devshirme system ensured a constant influx of highly trained and loyal soldiers, free from tribal or noble allegiances. By removing Janissaries from hereditary ties, the Ottomans created an elite force that was directly answerable to the sultan, ensuring discipline and unity.

🔫🛡️💣 Firearm Warfare and Combined Arms Tactics

Janissaries were among the first infantry forces to refine ranked volley fire, coordinated musket lines, and disciplined formations—centuries ahead of European line infantry doctrines. Their integration of musketry with cavalry charges and precision artillery became a blueprint for European military reform, as states sought to emulate the Ottoman model of standing, firearm-trained armies. When battle turned close and personal, Janissaries drew the kilij and yatagan—curved blades prized for their speed and cutting power. Their ability to transition fluidly between muskets, swords, and pikes ensured dominance in both open warfare and siege combat. In siege operations, they worked in concert with devastating Ottoman artillery, including the Great Turkish Bombard, which shattered fortifications like those at Constantinople (1453). Meanwhile, Bashi-bazouks—Ottoman irregulars—harassed enemy lines with raids and ambushes, softening targets before the Janissary advance.

🧘♂️📯🧠 Spiritual Training and Psychological Warfare

Beyond battlefield tactics, the Janissaries saw themselves as ghazis—holy warriors waging sacred struggle in service of the sultan and Islam. Their identity was shaped by Sufi teachings, which instilled discipline, humility, and the belief that death in battle was a path to honour and divine reward. This spiritual framework fostered unwavering loyalty and fearless resolve, making Janissaries not only elite soldiers but warriors of conviction.

Psychological warfare was central to their battlefield dominance. The Mehter (Janissary war band) blasted thunderous rhythms of drums, horns, and cymbals across the field, designed to shake enemy morale and energise Ottoman ranks. The relentless cadence created a sonic wall of intimidation, signalling not just the presence of troops—but a force unified in spirit and steel.

This fusion of faith, fearlessness, and psychological pressure made the Janissary Corps one of history’s most formidable military units—revered, feared, and widely emulated.

💪🏽 🛢️🤼♂️ Yagh Gures (Oil Wrestling)

Yagh Gures, or Turkish oil wrestling, traces its roots to ancient Turkic grappling traditions and became a key pillar of Janissary training. Wrestlers, covered in olive oil and wearing kispet (thick leather trousers), engaged in gruelling contests of strength, endurance, and technique. The oil’s slippery nature forced fighters to master strategic grips, leverage, and counters, blending raw power with refined skill.

Far more than entertainment, Yagh Gures served as battlefield conditioning, honing close-combat skills for real engagements. Many Janissaries trained as wrestlers, learning takedowns, grip breaks, and body control essential in tight melee or when armour rendered slashing attacks ineffective. The Kirkpinar tournament, held annually since 1362, remains the world’s longest-running wrestling competition, preserving this warrior legacy.

🤼♂️🗡️🔁 Wrestling in Janissary Combat Training

Oil wrestling built skills that translated directly to war: joint control, takedowns, ground dominance, and spatial awareness in chaotic conditions. These techniques were crucial in disarming or subduing enemies at close quarters, particularly when formations broke down. The ability to manipulate an opponent’s weight, counter grips, and fight in slippery conditions translated directly to grappling in armour, restraining enemies, or disarming foes on the battlefield. Wrestling also developed resilience and grit, giving Janissaries the endurance to maintain control in prolonged engagements.

🧘🏽♂️🔥🫱 Spiritual Discipline and the Warrior Ethos

While Yagh Gures served as rigorous physical conditioning, it also mirrored the spiritual discipline found across the Janissary ranks. Wrestlers trained under the Pehlivan code—a warrior ethic rooted in humility, perseverance, and honour. This aligned closely with the Sufi-inspired values already ingrained in Ottoman military life, reinforcing mental resilience, pain tolerance, and emotional control under pressure.

Wrestling wasn’t merely a test of strength—it was a spiritual practice in motion, demanding inner focus, submission to struggle, and mastery over the self. This blend of combat readiness and inner discipline ensured Yagh Gures remained a living tradition, embodying the soul of Ottoman martial culture as much as its physical prowess.

The Ottoman Janissary corps underwent rigorous training in archery, wrestling, swordsmanship, and discipline, forging elite soldiers known for their cohesion, endurance, and mastery of close-quarters combat.

Far East 🐉🗻⚔️

China ⚔️🇨🇳🐉 🏯

Ming Dynasty

Under the Ming dynasty, martial arts flourished in a world still shaped by war, rebellion, and expanding borders. With threats from pirates, bandits, and nomadic incursions, the state turned to monks, militias, and professional fighters to defend the realm. Shaolin warriors were deployed beyond temple walls, escort agencies protected trade routes, and military manuals codified battlefield techniques. Martial arts were not hidden—they were sharpened for service. This section explores how combat evolved in a time of national defence, state support, and the growing need for disciplined, adaptable warriors.

Click on the links below to read more.

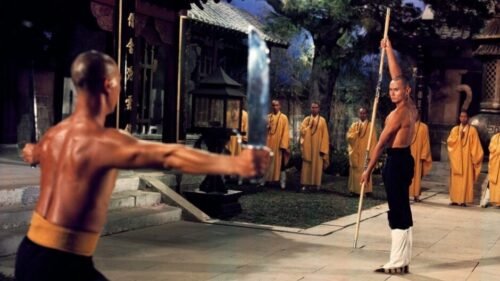

🥋🥋🥋🏯 Shaolin Monks and Battlefield Contributions

By the Ming era, Shaolin monks had moved beyond temple defence and philosophical training—their battlefield role had matured into a specialised form of regional warfare. In times of unrest, they were deployed to suppress banditry and defend key territories, particularly in mountainous regions where conventional troops struggled. Their combat approach blended guerrilla-style tactics, ambush formations, and terrain-based strategy, reflecting their adaptation to decentralised conflict.

Unlike earlier centuries where Shaolin fighters were spiritual warriors who occasionally assisted emperors, Ming-era monks operated as disciplined martial units. Their use of unconventional weapons such as the guan dao, three-section staff, and twin sabres reflected both innovation and practicality—tools suited for fast, decisive engagements in unpredictable terrain.

What set them apart was not just martial skill, but mental discipline. Rooted in Buddhist philosophy, their training reinforced patience, resilience, and moral clarity amid chaos. In a time of military flux, Shaolin warriors proved that spiritual systems could remain tactically relevant in evolving warfare.

⚪🈶☯️ The Rise of Internal Styles and Close-Quarters Combat

The late Ming and Qing periods saw the rise of short-range martial systems, designed for urban defence, bodyguard duties, and military contexts. These styles emphasised explosive power, disruption, and adaptability—ideal for confined spaces and rapid engagements.

🔹 Bajiquan – Known for explosive strikes, elbow techniques, and joint-breaking attacks, it became favoured in imperial bodyguard training. Its short-range power and bone-crushing force made it ideal for sudden engagements in crowded quarters.

🔹 Tibetan Martial Arts (Lama Pai & Lion’s Roar) – Integrated staff, grappling, and circular footwork, influencing Northern Shaolin traditions and providing adaptable systems for warriors in varied terrain.

🔹 Taijiquan & Bagua Zhang – While later associated with health practices, these internal styles were also part of military training. Soldiers trained in these arts developed redirection techniques, enhanced reaction timing, and evasive strategies—particularly useful against larger or heavily armed opponents.

🔹 Emeiquan (Emei Mountain styles) – Blended Buddhist and Daoist spiritual principles with intricate handwork, deceptive footwork, and pressure point attacks. Though less known, these systems added a refined, often underestimated dimension to the martial arts landscape—spiritually rooted yet highly combative.

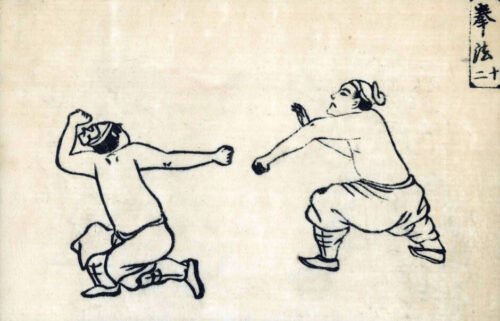

📖🪖📏 Military Manuals and the Codification of Combat

The Ming and Qing periods saw the formalisation of military and martial knowledge through texts such as the Wubei Zhi (Treatise on Military Preparedness). This massive compendium codified tactics, weapon drills, and combat formations, creating a shared reference for the imperial army and civilian schools alike. It documented spearmanship, cavalry formations, and gunpowder integration, ensuring that martial systems remained functional and adaptable. This period marked the evolution of Chinese martial arts from battlefield application to structured systems—preserving combat knowledge while expanding training beyond warfare into education and culture.

The three-section staff is one of Shaolin’s most advanced weapons, valued for its unpredictability and versatility. It requires exceptional control and coordination, turning chained segments into a fluid weapon capable of striking, trapping, and defending from multiple angles.

Qing Dynasty

As China shifted from Ming rule to Qing conquest, martial arts faced a new threat—not from rival armies, but from within. The Manchu-led Qing dynasty imposed strict controls on the Han population, suppressing traditional culture and viewing martial training with suspicion. In response, combat arts went underground. Temple guardians and secret societies preserved techniques in secrecy, while monks and performers passed knowledge through ritual and theatre. In crowded cities, styles grew tighter and deadlier—designed for back alleys, bodyguards, and sudden violence. This section explores how combat survived amid censorship, conflict, and cultural reinvention.

Click on the links below to read more.

🤐🎎🩸 Martial Arts and Secret Societies

As Qing authority expanded, many martial systems went underground—preserved not in armies, but in secret societies like the White Lotus, Heaven and Earth Society, and Red Turbans. These groups used martial training to cultivate loyalty, identity, and resistance among Han Chinese members under Manchu rule. Techniques were passed through coded forms, ritual practice, and oral lineage, preserving combative knowledge while embedding subtle political messages. In this hidden world, martial arts were more than self-defence—they became instruments of rebellion and symbols of cultural defiance, ensuring survival through secrecy.

🚫🧳🌏 Manchu Suppression and the Diaspora of Martial Knowledge

Under Qing rule, the Manchu elite sought to suppress Han identity, dissolving Ming loyalties and tightening control over Chinese cultural expression. Martial arts, especially those tied to Han resistance or secret societies, were seen as threats to state authority. Schools were shuttered, weapons were restricted, and lineages were forced underground. In response, many martial artists, monks, and rebel-affiliated families fled China—seeking refuge in Southeast Asia, the Americas, and beyond. With them travelled their traditions: hidden forms, family styles, healing arts, and philosophical codes. These refugees would become the founders of overseas Chinatowns and Tongs, blending martial preservation with community protection. What began as resistance under occupation became the global seedbed of Chinese martial culture, rooted in exile but destined to endure.

🎭🐒🍶 Martial Arts in Chinese Opera and Folk Performance

While imperial forces monitored temples and militias, martial arts found cover in the most unlikely place—theatre. Travelling opera troupes, martial storytellers, and street performers used stylised movement, rhythm, and dramatic expression to mask real techniques. Styles like Monkey Fist, Drunken Boxing, and Eagle Claw were performed as entertainment, but beneath the acrobatics lay practical combat skills. Through storytelling and spectacle, these performers became unofficial archivists, keeping martial traditions alive across regions. It was combat disguised as culture, preserved through performance when formal transmission was forbidden.

🏘️🤜🧍Urban Combat and the Rise of Confined-Space Systems

With warfare no longer fought on open plains, martial arts evolved to suit the chaos of urban life. In crowded towns and narrow alleyways, fighters needed fast, efficient, close-quarters techniques. Systems like Wing Chun, Southern Praying Mantis, and White Crane focused on interception, centreline control, and rapid takedowns—built for real threats in tight spaces. These styles were refined by bodyguards, militia, and security escorts, trained to neutralise danger with minimal motion. Urban combat demanded not showmanship, but survival—a shift from extended forms to explosive, direct action.

🛡️🚶♂️🚨 Bodyguard Systems and Urban Defence

The growing need for protection in cities and during travel gave rise to bodyguard-specific martial systems, adapted for street-level conflict and confined spaces. Martial artists in security escort agencies (biaoju), merchant caravans, and urban militias prioritised tactics for rapid takedowns, deception, and tactical awareness. Arts like Bajiquan, Wing Chun, and Liuhebafa gained popularity among professional guards, blending aggressive entry techniques with centreline control and situational reflexes. These close-quarters arts formed a bridge between personal self-defence, professional protection, and battlefield heritage.

🥊🪵🗣️ Lei Tai and the Culture of Public Duelling

The Qing era witnessed a rise in public duelling on Lei Tai platforms—raised arenas where martial artists competed with minimal rules. These challenge matches drew fighters from temples, militias, and military units, serving as both recruitment tests and displays of technical skill. Victors earned reputations and opportunities, while audiences witnessed firsthand which techniques held up under pressure. Though sometimes ritualised, many contests were brutal and uncompromising—reinforcing the combat reality behind martial arts and filtering out ineffective styles.

🏮🥋📜 Martial Arts as Cultural Symbols

By the late Qing Dynasty, Chinese martial arts had grown into more than just combat systems—they had become expressions of national identity and cultural resilience. Folk heroes like Wong Fei-hung and the defenders of southern temple systems embodied this spirit, balancing combat mastery with moral integrity. Martial arts became tools of personal transformation, spiritual cultivation, and cultural storytelling, setting the stage for their next evolution into performance, film, and national pride. The symbolic power of martial discipline began to eclipse its battlefield role, yet its combative essence remained preserved in forms, drills, and philosophy.

📣✊🏽🌍 The Boxer Rebellion and Martial Arts on the World Stage

As the Qing Dynasty neared collapse, the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901) thrust Chinese martial arts into the global spotlight. Rebel groups known as the Righteous and Harmonious Fists believed their combat training and spiritual rituals could make them impervious to bullets—merging ancient discipline with desperate defiance against foreign dominance. Though ultimately overwhelmed by imperial forces, their uprising marked the first time outsiders directly encountered China’s indigenous fighting arts, albeit often misunderstood and sensationalised as “Chinese boxing.”

The rebellion marked both an end and a beginning. Defeated in battle but not in spirit, China’s martial traditions would not vanish with the Boxers’ fall. Instead, they began to drift beyond China’s borders, carried by refugees, merchants, and warriors seeking survival. In exile, these arts found new life, transforming from local resistance systems into global symbols of resilience. In the shadow of defeat, the seeds of worldwide transmission were sown—setting the stage for the next chapter in the evolution of Chinese combat arts.

Chinese Opera became a hidden sanctuary for martial artists during the Qing dynasty, where stylised fight scenes masked real combat training and preserved traditional techniques under the guise of performance.

Okinawa 🏝️🥋⚔️

Caught between empires and sea routes, Okinawa emerged as a cultural crossroads where martial traditions collided and fused. With Chinese traders arriving from Fujian and Japanese influence pressing from the north, local warriors absorbed, adapted, and redefined their fighting systems. Stripped of weapons by outside rule, Okinawan martial artists turned to empty-hand strikes and improvised tools—refining raw necessity into structured, lethal efficiency. This section explores how a small island forged a legacy of resilience through fusion, adaptation, and the quiet mastery of both hand and weapon.

Click on the links below to read more.

🌏🥋🤝 Martial Arts Crossroads

Okinawa, positioned between China’s Fujian province and Japan’s southern islands, became a vital crossroads for cultural and martial exchange—especially during the Ryukyu Kingdom’s golden age as a tributary to China. Traders travelling the Maritime Silk Road brought not only goods but fighting knowledge. Local Te (“hand”) combat, originally focused on strikes and joint locks, fused with Southern Chinese systems like White Crane Kung Fu. This blend introduced circular techniques, explosive power, and grounded stances, evolving Okinawan methods into a more structured and refined combat system.

Chinese martial arts contributed key elements such as:

- Tension-based breathing (ibuki): Boosting close-range power and mental control.

- Deflection-style blocks: Enhancing counterattacks with redirection instead of force.

- Iron Body & breath training: Forging physical resilience and internal focus.

- Kata (forms): Instilling muscle memory, strategy, and spiritual discipline.

These refinements elevated Okinawan self-defence, especially crucial under government-imposed bans on weapons.

🚫🗡️🌾🔧🥢 The Rise of Kobudo & Weapons Bans

The Peichin warrior class—elite bureaucrats trained in martial arts—played a central role in Kobudo, transforming everyday farming tools into deadly weapons. Their adaptations birthed iconic tools like the bo (staff), sai (trident), tonfa (mill-handle), kama (sickle), and nunchaku (flail), allowing covert self-defence in an era of surveillance and restriction.

After the 1609 Satsuma invasion, the banning of conventional weapons drove innovations in both unarmed combat and concealed weapons training. Techniques from Chinese spear and staff systems influenced this evolution, and by the 18th century, Kobudo had become a formalised system of weaponised self-defence.

Weapons loss also reshaped Okinawan Karate through:

🔹 Improvised weapon training – Turning tools and objects into defence tools.

🔹 Group-based defence tactics – Fending off multiple or armed attackers.

🔹 Weapon disarm drills – Techniques to counter swords, spears, and other threats.

🌍🥋📈 From Okinawan Roots to Global Recognition

As Karate spread beyond Okinawa, it was systematised and adapted to new cultural contexts.

🔹 Shotokan Karate (Gichin Funakoshi): Emphasised longer stances, linear strikes, and Japanese aesthetic, aligning Karate with bushido and modern education.

🔹 Goju-Ryu Karate: Preserved more of its Southern Chinese essence, emphasising close-range power, circular blocks, and breath control.

By the 20th century, Karate had evolved from a regional survival method into a global martial discipline, carrying the legacy of Okinawa’s fusion culture while adapting to military, sporting, and civilian needs across the world.

The Bubishi – A treasured Chinese manual that shaped Okinawan Karate, blending combat strategy, pressure point theory, and martial philosophy into a foundational text for generations of Karate practitioners.

Japan 🗾⚔️🎎

The Samurai

During the turbulent centuries of the Sengoku Jidai (Warring States Period), Japanese martial arts were forged not just through bloodshed, but through discipline, legacy, and refinement. As clans rose and fell, their warriors codified the chaos into ryu—formalised schools designed to preserve knowledge, perfect technique, and pass down the soul of combat from one generation to the next. This section explores how Japan’s battlefield systems evolved into lifelong paths of mastery—where swords, spears, and spirit became one.

Click on the links below to read more.

🏯📜🥋 Traditional Martial Schools (Ryu)

Samurai clans formalised their martial systems into distinct ryu—structured Japanese martial arts schools that preserved kenjutsu (swordsmanship), iaijutsu (sword drawing), sojutsu (spear combat), and jujutsu (grappling) as family-guarded traditions. Each ryu developed specific techniques, drills, and kata (forms) to maintain battlefield effectiveness and ensure the legacy of their clan’s fighting methods.

Kenjutsu, while symbolic of the samurai, was often secondary on the battlefield. Sojutsu spear formations and mounted archery were dominant in large-scale warfare, while swords were reserved for close-quarters combat, castle sieges, and honour duels. The katana and wakizashi (short sword) remained key tools for decisive encounters, prized for their speed, precision, and symbolic power in personal combat.

🎯🏹🗡️ Beyond the Sword: The Full Arsenal of the Samurai

The naginata, a polearm with a curved blade, allowed for powerful sweeping attacks and extended reach, ideal for controlling space and fending off cavalry. It was notably wielded by Onna-Bugeisha (female warriors), who were trained to defend homes and castles with formidable skill.

Kyudo (archery) served as the foundation of samurai warfare in earlier periods, especially during the Heian and Kamakura eras, where mounted archers exchanged volleys in ritualised skirmishes. On foot, archers played a vital role in softening enemy lines before the final charge into melee combat.

In close-range encounters, kumiuchi—the grappling techniques used in full armour—taught samurai to control opponents through throws, joint locks, and disarms, often setting up a finishing blow with a tanto or wakizashi. These techniques prioritised balance disruption and armour-specific leverage, essential in the chaos of battlefield collisions.

A lesser-known yet equally refined practice was Hojo-jutsu, the art of rope restraint. Originally used to secure prisoners, it developed into a formal system for capturing and subduing opponents without lethal force—reinforcing the samurai’s mastery over violence, control, and justice.

🧘♂️🗡️🕊️ Zen Influence and the Rise of Bushidō

The evolution of these arts was deeply tied to the spiritual and ethical framework of Bushidō, which matured during the relative peace of the Edo period. More than just battlefield systems, martial arts became a way of life—blending honour, discipline, and moral conduct with combat proficiency. Warriors trained not only to fight but to live—and die—with purpose.

Zen Buddhism shaped this mindset profoundly. Through zazen (seated meditation) and the pursuit of mushin (no-mind), samurai sought a state of calm detachment and spontaneous action—critical in both duels and chaotic warfare. This mental clarity, free from ego and hesitation, ensured fluidity, decisiveness, and fearlessness in the moment of truth.

Together, these integrated systems elevated Japanese martial arts beyond mere techniques of war. They became instruments of spiritual development, social order, and cultural identity, forging a warrior legacy that would continue to shape Japan long after the swords were sheathed.

Samurai unarmed training included grappling arts like kumi-uchi, used in armour-clad combat to control or throw opponents, and hojo-jutsu (below), the intricate art of rope-tying for restraining captives—both reflecting the samurai’s need for close-quarters skill beyond the sword.

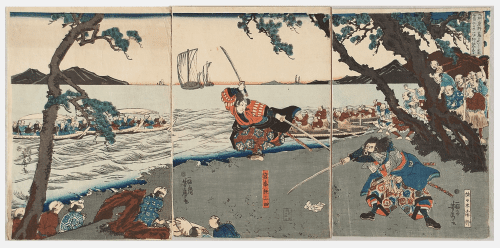

Miyamoto Musashi 👤⚔️📚

Amid the blood-soaked chaos of the Sengoku Jidai—an age of fractured clans, shifting alliances, and survival by the sword—true mastery was forged not in courts, but in combat. Miyamoto Musashi stood apart—not as a polished court retainer, but as a ruthless ronin who mastered both blade and mind. His duels became legend, his tactics rewrote the rules, and his writings still echo through dojos and war rooms alike. This section explores how Musashi transformed combat from formality into philosophy—through rhythm, deception, and the relentless pursuit of mastery.

Click on the links below to read more.

🛖 ⚔️🧘🏽♂️🥋 Unorthodox Samurai

Miyamoto Musashi (1584–1645), perhaps Japan’s most iconic duellist and strategist, represents a radical shift in samurai combat philosophy. Born in Harima Province, he reportedly fought—and won—his first duel at the age of 13. As a young man, he fought in the pivotal Battle of Sekigahara (1600) on the losing Western side, opposing Tokugawa Ieyasu. Surviving the aftermath, Musashi never entered the service of a daimyo and instead lived as a ronin—a masterless warrior. He embraced the path of musha shugyō, a wandering journey of self-perfection through real combat.

Over the next few decades, Musashi traversed Japan, challenging martial schools and defeating over 60 opponents in formal duels. His outsider status freed him from traditional constraints, allowing him to adopt a ruthless, adaptive style rooted in real-world efficiency. From this experience, he developed Niten Ichi-Ryū (“Two Heavens, One School”)—a revolutionary system that employed both the katana and wakizashi simultaneously in combat.

While most samurai reserved the wakizashi for indoor or emergency defence, Musashi’s method used both blades in tandem to overwhelm opponents with:

🔹 Relentless offence – Sustained pressure to overwhelm an adversary’s rhythm.

🔹 Defensive versatility – Fluid transitions in distance and angular control.

🔹 Unorthodox movement – Exploiting the rigidity of traditional forms and timing.

Though this dual-sword approach proved lethal in one-on-one combat, it was less suited for traditional battlefield roles, where spears and heavier weapons remained dominant due to their reach and armour penetration.

🧠⏱️🎭 Psychological Warfare and Strategic Brilliance

Musashi’s greatest strength wasn’t just in wielding blades—it was in wielding fear, perception, and rhythm. He understood that combat was as much mental as it was physical, mastering the art of hyōshi (timing) to disrupt his opponents’ flow and seize initiative.

🔹 The Yoshioka Clan Duels – He dismantled the Kyoto-based family’s leadership through a sequence of duels, ending in a final confrontation where he eliminated multiple assailants alone using ambush tactics.

🔹 The Duel with Sasaki Kojiro – Musashi arrived deliberately late, throwing Kojiro off balance. Armed with an improvised bokken carved from an oar, he baited Kojiro into overextending and struck with a single decisive blow.

These weren’t just victories—they were demonstrations of tactical manipulation, showcasing how psychological dominance and deception could neutralise even the most skilled adversaries.

📖🌍💧🔥🌪️🌀 The Book of Five Rings – A Legacy of Strategy

In his later years, Musashi entered the service of the Hosokawa clan, where he composed his enduring work: the Go Rin no Sho (Book of Five Rings, 1645). Divided into five scrolls—Earth, Water, Fire, Wind, and Void—the text presents Musashi’s combat philosophy, blending martial technique with psychological insight.

His principle of Ku (Void) taught that a warrior must remain fluid and formless, responding without hesitation or attachment. This ideal heavily influenced later arts such as Kendo, Iaido, and Jujutsu, where timing, adaptability, and mindset are paramount.

Musashi’s teachings continue to transcend centuries and disciplines. His lessons on distance control, rhythm, mindset, and strategic awareness remain relevant not only in martial arts and MMA, but in military training, business strategy, and personal development. A master of blade and mind alike, Musashi endures as a symbol of tactical brilliance, self-evolution, and the unrelenting pursuit of mastery.

Japanese woodblock prints of the duel between Miyamoto Musashi and Sasaki Kojiro immortalise one of Japan’s most legendary sword fights—capturing not just a clash of blades, but a battle of styles, strategy, and warrior spirit.

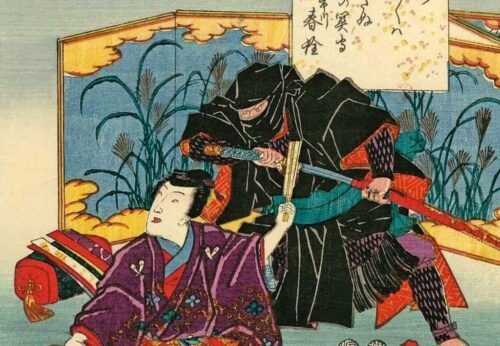

The Peak of Shinobi Warfare 🥷🌒🔥

During the height of the Sengoku Jidai, shinobi operatives reached the peak of their strategic influence—quietly shaping the outcomes of Japan’s civil wars through espionage, sabotage, and infiltration. But as the Tokugawa shogunate brought unity and stability, these covert specialists found their roles increasingly restricted. Once essential to wartime tactics, many were disbanded, absorbed into state structures, or forced underground. This section explores their tactical legacy, from their most impactful operations to their quiet transformation under a regime built on order and control.

Click on the links below to read more.

📈⚔️📉 The Rise and Fall of Japan’s Shadow Warriors

The Sengoku period (1467–1600) marked the golden age of the shinobi, as the Iga and Kōga clans rose to prominence as elite mercenaries during Japan’s fractured civil wars. Daimyō across the country hired them for espionage, infiltration, sabotage, and targeted assassinations—roles that blurred the line between open warfare and strategic deception. Figures like Hattori Hanzō became icons of this clandestine world, elevating the shinobi’s reputation as masters of subterfuge and psychological warfare.

But their autonomy invited danger. In 1579, Oda Nobunaga launched a brutal campaign against Iga Province, seeking to destroy its covert warrior networks and sever links to rebellious sects like the Ikkō-Ikki. A larger invasion in 1581 devastated the region—villages were burned, and thousands of shinobi operatives and their families were slaughtered or scattered. Survivors fled underground, often entering rival domains as covert agents, or adapting their skills for the shifting needs of Japan’s unifying military elite. Despite the loss of their homelands, their talents remained in demand. During the Siege of Osaka (1614–1615), Tokugawa Ieyasu reportedly deployed former Iga and Kōga operatives to sabotage fortifications, spread disinformation, and ignite fires under cover of darkness. These missions represent one of the final large-scale uses of traditional shinobi warfare on the battlefield.

🌫️👁️🏯 From Shadows to Surveillance: The Shinobi in Tokugawa Japan

With Tokugawa’s triumph and the onset of peace under the Edo period (1603–1868), the era of autonomous shinobi clans came to a close. Yet their legacy endured. The shogunate is believed to have retained some operatives as “gardeners” within castle grounds—a discreet euphemism for embedded spies. These agents monitored internal movements, gathered intelligence, and served as a silent security presence in a regime that prized order above all.

No longer warriors of chaos, the shinobi were transformed into custodians of control—the unseen blade behind the shogun’s calm. Though their battlefield role faded, their methods of surveillance, misdirection, and psychological manipulation were never fully lost—only repurposed for an era that demanded quiet dominance over open warfare.

⛰️🥷📜 Iga and Koga Clans

Though often grouped together, the Iga and Kōga shinobi developed distinct methods, structures, and reputations—shaped by their geography, politics, and internal traditions.

🗻 Iga Clan (Iga Province)

📍 Mountainous, isolated terrain ideal for guerrilla tactics and secrecy.

🧠 Known for structured training, written manuals (e.g., Bansenshukai), and formal ranks.

👥 Organised in small, tight-knit families—each with unique specialisations.

🔥 Tactics focused on infiltration, terrain sabotage, escape and evasion, and covert intelligence gathering.

Famous Figure: Hattori Hanzō – Bodyguard to Tokugawa Ieyasu; symbol of Iga’s strategic excellence.

🌾 Kōga Clan (Ōmi Province)

📍 More accessible plains region, allowing wider social interaction and integration.

🕵️ Known for adaptability and widespread deployment as mercenaries.

🪓 More decentralised—Kōga families operated with tactical autonomy.

🎯 Favoured long-range reconnaissance, disinformation campaigns, and contact poisons in rare high-risk missions.

Legacy: Kōga operatives were often used for extended surveillance and embedded roles within enemy courts or towns.

Shinobi activity peaked during Japan’s Sengoku period (c. 1467–1603), a time of constant warfare when feudal lords employed ninja for espionage, sabotage, and infiltration—making them crucial players in the era’s shadow warfare.

Korea 🇰🇷⚔️🥋

Caught between dynastic ambitions and foreign invasions, Korea’s martial traditions were forged in conflict and defined by resilience. From the battlefield discipline of the Hwa Rang to the refined codification of Joseon-era manuals, Korean warriors adapted to changing warfare through tactical diversity and ethical strength. This section explores how Korea’s combat systems balanced honour with adaptability—shaping elite warriors, grappling methods, and striking arts that endured long after the smoke of battle cleared.

Click on the links below to read more.

🛡️🐎🌸 Hwa Rang – Korea’s Elite Warrior Leaders

Korea’s martial evolution was profoundly shaped by the Hwa Rang of the Silla Kingdom—an elite youth order trained in archery, swordsmanship, cavalry tactics, and military strategy. These warrior-leaders spearheaded shock cavalry formations and executed flanking manoeuvres against Baekje and Goguryeo, playing a central role in the unification of the Korean Peninsula.

More than just fighters, the Hwa Rang adhered to a strict ethical code—Hwa Rang Do—which emphasised loyalty, courage, honour, and moral integrity. This code would later parallel Japan’s Bushidō, becoming the philosophical foundation of Korean martial traditions and influencing warrior identity for generations.

🌀🦶🎯 Taekkyeon – Dynamic Footwork and Combat Adaptation

Taekkyeon, one of Korea’s oldest martial systems, emphasised fluid footwork, deceptive rhythm, sweeps, and high kicks. Though often overshadowed by Taekwondo, Taekkyeon was originally developed for battlefield skirmishes, mounted defence, and urban combat.

🔹Evasion & Control – Feints and angular steps disrupted enemy balance and manipulated range.

🔹Joint Locks & Low Strikes – Effective against armoured foes or in confined terrain.

🔹Combat Versatility – Transitioned between open-field warfare, guerrilla tactics, and civilian self-defence.

Taekkyeon’s adaptive movement and rhythm-based tactics made it a key link in the evolution of Korean close-combat systems.

📚🎯🏹 Joseon Martial Systems & Battlefield Manuals

Under the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897), Korea’s martial practices were formalised and refined. Influenced by Ming Dynasty doctrine, Korea produced the landmark treatise:

Muye Dobo Tongji (Comprehensive Illustrated Manual of Martial Arts)—a detailed codification of both indigenous and foreign techniques.

🔹Spears & Polearms – Structured drills based on Chinese formations with Korean modifications.

🔹Mounted Archery – A continuation of steppe warfare tactics, focusing on mobility and precision.

🔹Swordsmanship – Blended Chinese fencing, Japanese influences, and Korean adaptations suited to duels and battlefield scenarios.

This manual preserved a wide range of techniques, ensuring Korea’s martial arts were not lost in peacetime but carried forward into modern times.

🤼♂️🪖🔗 Battlefield Ssireum – Grappling for Armoured Combat

Distinct from today’s sporting version, battlefield Ssireum emerged as a grappling system optimised for heavily armoured conditions. It complemented striking arts by offering control and finishing techniques at close range when weapons were lost or combat closed in.

Techniques included:

🔹 Low-gravity takedowns.

🔹 Standing clinch control.

🔹 Joint locks to disable or disarm enemies.

These methods enabled Joseon warriors to maintain dominance in confined or chaotic conditions, often acting as the deciding factor when swordplay alone wasn’t enough.

🤼♂️🪖🔗 Legacy and Transition

From the ethical leadership of the Hwa Rang to the adaptive striking of Taekkyeon and grappling realism of Ssireum, Korea’s martial traditions fused moral philosophy with tactical innovation. These arts were never mere rituals—they were forged for survival, honed during civil wars and foreign invasions alike.

With the creation of manuals like the Muye Dobo Tongji, Korea ensured its martial legacy was documented, preserved, and passed on. While many systems evolved into modern sports or cultural practices, their combat roots remained central to their identity. Today, Korea’s martial heritage stands as a vital chapter in the story of East Asian combat evolution—bridging discipline and adaptability, honour and technique.

Korea’s Hwarang were elite warrior youths of the Silla dynasty, trained in martial arts, strategy, and Confucian-Buddhist philosophy—blending combat with moral discipline.

Warrior Systems of Southeast Asia 🌴⚔️⛵

Forged in jungles, coastal villages, and shifting kingdoms, Southeast Asia’s martial traditions emerged from a blend of indigenous innovation, Indian and Chinese influence, and the practical demands of guerrilla warfare and naval defence. These systems prioritised adaptability, deception, and close-quarters dominance, reflecting a region defined by hybrid tactics, tribal conflict, and strategic terrain. From jungle ambushes to shipboard skirmishes, Southeast Asian warriors developed combat systems based on speed, precision, and improvisation—laying the foundation for enduring, dynamic martial arts.

Click on the links below to read more.

🇵🇭🌀🗡️ Filipino Martial Arts: Arnis, Eskrima, and Kali

In the Philippines, native fighting styles evolved through centuries of raiding warfare, naval skirmishes, and Spanish colonisation. Pre Colonial warriors wielded kampilan swords, bolos, spears, and shields in dual-weapon tactics suited to ambushes and mobile strikes.

Under Spanish rule, Filipino martial arts absorbed elements of European fencing, introducing angular strikes, footwork drills, and disarm techniques. The resulting systems—Arnis, Eskrima, and Kali—varied by region but shared a focus on:

🔹Weapon-to-empty-hand flow

🔹Rapid striking sequences

🔹Footwork and redirection under pressure

These arts emphasised versatility, training fighters to shift seamlessly between weapons, traps, and strikes.

🌑🕷️🥷 Silat: The Martial Art of Deception

In Indonesia and Malaysia, Silat emerged as a system of fluid movement, concealment, and precise targeting. Designed for combat in dense terrain or confined spaces, Silat employed:

🔹Low stances and feints

🔹Joint manipulation and tendon slashes

🔹Weapons like the karambit and keris

Silat fused tribal ritual, internal energy concepts, and ambush strategy, making it both a spiritual practice and a brutally effective combat art.

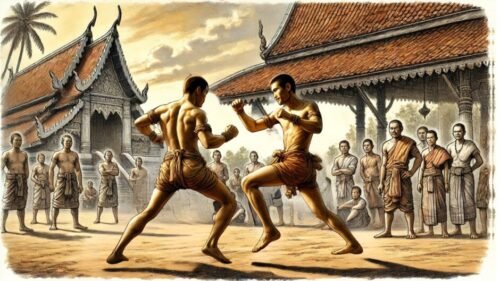

🇹🇭🦵🛡️ Thailand’s Muay Boran & Krabi-Krabong

Thai martial culture developed two distinct yet complementary systems:

🔹Muay Boran was a brutal empty-hand style built for close-quarters survival, using knees, elbows, clinch grappling, and headbutts when weapons were lost.

🔹Krabi-Krabong taught armed combat with paired swords (daab), staves, spears, and shield formations for large-scale battle.

These systems were tested in elephant warfare, jungle clashes, and infantry flanking manoeuvres, forming the military core of Thai warfare. While Muay Boran later evolved into Muay Thai, its original purpose was battlefield dominance through aggressive anatomical targeting.

🇰🇭🐘🤼 Cambodia’s Bokator: The Art of the Battlefield

Rooted in the Khmer Empire, Bokator was developed for siege warfare, elephant-mounted combat, and jungle fighting. This system combined:

🔹 Bone-breaking strikes and joint locks

🔹 Throws, takedowns, and clinch control

🔹 Weapon integration and dismount techniques

Even elephant riders were trained in grappling and recovery, showing the system’s attention to layered battlefield roles. Bokator was designed for swift, decisive outcomes in the chaos of multi-level combat.

🇲🇲💥🧠 Myanmar’s Lethwei & Banshay

In Myanmar, Lethwei emerged as a raw, aggressive striking system—feared for its use of headbutts, relentless forward pressure, and preemptive violence. Unlike the reactive flow of Muay Boran, Lethwei focused on immediate dominance.

Complementing it was Banshay, the armed discipline of Myanmar’s warriors. It included:

🔹Sword and spear combat

🔹Archery and formation-based training

🔹Elite infantry and royal guard tactics

Together, these arts addressed both personal combat and battlefield versatility, reflecting Myanmar’s need for agility across multiple terrains and threats.

🇻🇳🎯🌿 Vietnam: Resistance, Strategy, and Traditional Martial Arts

Vietnam’s martial identity developed under centuries of foreign pressure, particularly Chinese imperial rule. This shaped systems rooted in mobility, deception, and terrain adaptation. Early warriors used swords, polearms, spears, and concealed blades, excelling in:

🔹Ambush and guerrilla resistance

🔹Naval raids and jungle tactics

🔹Strike-to-grapple transitions under pressure

Systems like Võ cổ truyền integrated these principles, combining fluid transitions between striking and grappling. While Vovinam emerged in the 20th century, it drew from traditional battlefield strategies, including throws, joint locks, and low-line attacks. Though influenced by Chinese staff methods, Vietnam’s martial traditions remained fiercely independent—defined by their asymmetric warfare and tactical resilience.

🌳⚔️🤔 Jungle Tactics: What Made Southeast Asian Martial Arts Unique?

Southeast Asia’s martial systems weren’t born in dojos or palaces—they were forged in jungles, mountains, rivers, and coastal strongholds, shaped by the practical demands of survival, tribal warfare, and resistance. Here’s what made them distinct from many other traditional martial arts:

🌀 Fluidity Over Formality

Rather than rigid kata, these systems emphasised movement flow, rhythm disruption, and seamless transitions between weapons and empty hands.

🗡️ Weapon Integration from the Start

Practitioners didn’t “graduate” to weapons—sticks, blades, and spears were primary tools from day one, often improvised from local tools or farming implements.

🫧 Environmental Adaptation

Combat systems were adapted for:

- Dense jungle (Silat’s low stances & concealment)

- Muddy terrain (Ssireum’s low takedowns)

- Shipboard fighting (Kali’s angular footwork & close-range strikes)

🧠 Deception as a Core Strategy

From Silat’s feints and sudden drops to Lethwei’s preemptive aggression, psychological manipulation and misdirection were baked into the DNA of combat.

⚔️ Ambush & Escape Mindset

Rather than prolonged engagement, many tactics focused on quick disables, fast finishes, and efficient escapes—reflecting guerrilla warfare and raid tactics.

🧬 Syncretic Roots

SEA martial arts often blended tribal animism, Indian metaphysics, and Chinese medical theory, producing styles that trained both mind and body, often with ritual or spiritual layers.

These weren’t arts of form—they were arts of function. From the jungles of Vietnam to the islands of the Philippines, Southeast Asian systems evolved as survival-driven martial philosophies built for war, resistance, and resilience.

When the Portuguese, led by Ferdinand Magellan, arrived in the Philippines in 1521, they encountered fierce resistance from native warriors skilled in Arnis—an indigenous stick and blade-fighting art. Magellan himself was killed in the Battle of Mactan.

Mughal India ⚔️🇮🇳🕉️🛕🐘

Between the temples of the south and the courts of the north, India’s martial traditions evolved through conquest, culture, and spiritual discipline. When the Mughal Empire took root, it brought Persian and Central Asian combat systems that merged with ancient Indian arts like Malla-yuddha. Wrestling, swordplay, and stick-fighting found new purpose under royal patronage—refined in akharas, tested in court, and sanctified by ritual. This section explores how India’s martial legacy adapted through fusion and resistance, producing systems of power, philosophy, and enduring cultural pride.

Mughal Wrestling Styles

Click on the links below to read more.

👑🛡️🏹 Combat in the Courts and on the Battlefield

The arrival of the Mughal Empire (1526–1857) marked a pivotal fusion point in Indian martial history. Descended from Turco-Mongol and Persian dynasties, the Mughals brought with them not only armies and imperial ambition, but a refined warrior culture rooted in grappling, cavalry tactics, and elite close-quarters combat. As their empire expanded across the subcontinent, so too did their influence on India’s indigenous martial traditions.

Under Mughal patronage, wrestling became both a courtly sport and a cultural institution. Royal arenas hosted grand matches, while dedicated akharas (wrestling schools) trained athletes in Pehlwani—a hybrid of Malla-yuddha, India’s ancient wrestling art, and Persian Koshti. But martial practice under Mughal rule went far beyond the pit. Regional styles flourished, developing systems of stick-fighting, swordplay, and striking arts that reflected the empire’s layered identities. This was an era where combat was cultivated not just for warfare, but for prestige, performance, and personal mastery.

🧬🤜🕌 The Synthesis of Malla-yuddha and Persian Pehlwani

The Mughal period saw a powerful cultural and martial synthesis. Indigenous Malla-yuddha, with its emphasis on strength, pressure point strikes, joint manipulation, and spiritual discipline, blended with Persian and Central Asian arts like Koshti and Varzesh-e Pahlavani, introduced by the Turkic and Persian elite. The result was Pehlwani (also called Kushti): a formidable grappling system that dominated South Asia.

Persian influence introduced club training (jodis/meels), refined grappling grips, and a strong tradition of courtly patronage. Mughal emperors established akhadas across the empire—many of which still exist today—cementing wrestling as a noble pursuit tied to masculinity, discipline, and physical excellence.

🎪🏛️🤼 Wrestling as a Mughal Court Sport

Wrestling was one of the most highly regarded athletic disciplines among the Mughal elite. Emperors like Babur, Akbar, and Jahangir sponsored matches at court and elevated skilled wrestlers (pehlwans) to positions of status. Wrestlers often served in the royal guard or participated in ceremonial displays of strength and skill.

🔹Akbar the Great famously constructed wrestling arenas at Fatehpur Sikri and kept skilled pehlwans as both entertainers and combat-ready guards.

🔹Texts like the Ain-i-Akbari document formal matches, wrestling festivals, and the emperor’s keen interest in physical culture.

🔹Victory in court-sponsored matches could lead to patronage, land grants, or military appointments.

🗡️💥🔒 Combat Relevance: From Sport to Survival

Though ritualised for court entertainment, Mughal-era wrestling retained its battlefield roots. Techniques drawn from Malla-yuddha and Pehlwani included:

🔹Throws and takedowns designed to slam or disable an opponent.

🔹Joint locks and chokes with battlefield relevance.

🔹Integration with dagger work (katar) and stick fighting, particularly in the context of personal duels and palace security.

Training was rigorous, often austere, focusing on raw power, explosive speed, breath control, and flexibility. Wrestlers were combat athletes in every sense.

🕉️☪️🧘 Cultural and Religious Influence

Wrestling during this era was not only physical—it was deeply spiritual:

🔹Hindu wrestlers followed the path of Brahmacharya (celibacy, discipline, and ritual purity), training in akhadas as both athletes and ascetics.

🔹Muslim wrestlers, often influenced by Sufi philosophy, viewed the practice as a form of inner submission and divine discipline—echoing parallels to Zoroastrian and Persian ideals of honourable combat.

🔹Daily rituals included mud-pit training (kushti mitti), yogic stretching, massages, and strict vegetarian or sattvic diets in many akhadas.

The result was a martial monasticism—combat as devotion, strength as virtue.

📜🏆🇮🇳 Legacy

The Mughals’ elevation of Pehlwani helped transform Indian wrestling into a lasting cultural institution. Wrestlers became symbols of martial discipline, moral strength, and national identity. While colonial rule would later reframe wrestling as spectacle or sport, the Mughal foundation ensured that grappling arts remained central to India’s martial soul—anchored in both combat functionality and spiritual refinement.

Pehlwani, also known as Indian wrestling, emerged through the fusion of traditional Malla-Yuddha with Persian Koshti during the Mughal era.

Gatka: The Sikh Warrior Tradition 🪯⚔️🛡️

As tensions escalated in the 17th century across northern India—particularly in Punjab—the expanding Mughal Empire clashed with the rising Sikh community, who resisted forced conversions and religious persecution. Gatka emerged in this crucible of resistance: a dynamic battlefield martial art rooted in the Khalsa warrior ethos (Sikh order of warrior-saints). Forged in defence of faith and community, Gatka trained warriors in fluid weapon transitions, relentless forward pressure, and inner resilience.

Click on the links below to read more.

🔄🎯🐎 Combat Techniques and Tactical Adaptability

Sikh warriors trained to be highly adaptive, capable of responding to rapidly shifting battlefield threats. Weapons such as the talwar (curved sword), kirpan (ceremonial dagger), barchha (spear), and chakram (throwing disc) allowed engagement at all ranges. The dual-sword method enabled simultaneous offence and defence, while circular panthra footwork disrupted enemy timing and neutralised cavalry charges.

Spinning strikes, angular counters, and fluid footwork made Gatka adaptable in both mounted and dismounted combat—especially against multiple opponents. While firmly rooted in traditional weaponry, Sikh martial culture also embraced evolving technology. Matchlocks, bows, and muskets were used alongside classical arms, influenced by both Dhanurveda principles and battlefield necessity. Nihang warriors, the most battle-hardened of the Khalsa, trained extensively in mounted combat, archery, and musketry, earning a fearsome reputation for tactical versatility.

🪯🧠🕊️ The Sant Sipahi Code and Akhara Training

Gatka was more than skill with a blade—it was a path of discipline, devotion, and spiritual clarity. In akhara (training halls), warriors honed not only their physical abilities but their mental and spiritual resilience. Training combined weapons drills, breath control, yogic conditioning, and meditation, reinforcing the Sikh belief that the mind must be as sharp as the sword.

The Sant Sipahi code demanded humility in peace and courage in battle. To wield a weapon without ego, to defend without hate—this was the essence of Sikh martial practice. Strength came not only from muscle, but from service, faith, and a willingness to protect the innocent at all costs.

Today, Gatka survives as a ceremonial, competitive, and cultural martial art, preserving the spirit of the Khalsa and a tradition born in faith and resistance.

Gatka is the traditional martial art of the Sikhs, developed as both a spiritual and practical system of combat. Rooted in the warrior teachings of the Khalsa, it emphasises bladed weapons, fluid movement, and rhythmic footwork.

Regional Combat Styles Found Throughout Mughal India

Mughal India was home to a diverse range of regional combat styles, each with its own unique focus and historical significance. The following table outlines some of these regional styles and their relevance during the Mughal era.

| Style | Region | Focus | Mughal-Era Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pehlwani | Pan-Indian | Grappling | Mughal court sport; evolved from Malla-yuddha + Persian wrestling |

| Thang-Ta | Manipur | Sword/spear & unarmed | Retained by warrior clans resisting outside influence |

| Silambam | Tamil Nadu | Staff & short weapons | Used in duels and militia training |

| Pari-Khanda | Bihar | Sword & shield | Preserved in martial dance; regional warrior art |

| Musti-yuddha | North India | Striking | Bare-knuckle tradition tied to ritual and duelling |

| Gatka | Punjab | Swordplay, multiple weapons, spiritual discipline | Developed in resistance to Mughal persecution; linked to Khalsa warrior ethos |

India’s Overlooked Martial Legacy ⚔️🇮🇳🕉️📜🐘

India’s contribution to the global evolution of martial arts is often overlooked, despite its deep and lasting influence across Asia. Systems like Kalaripayattu, Malla-yuddha, and the Dhanurveda laid the groundwork for sophisticated combat traditions that blended physical training with spiritual discipline. Through trade, religion, and cultural exchange—particularly via Buddhist monastic networks and maritime routes—these ideas travelled to regions like China, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia, where they helped shape martial practices from Shaolin Kung Fu to Southeast Asian weapon systems. This wider impact will be explored in greater detail in a separate post.

Africa 🌍🛡️🤜🏿

Across Africa, martial traditions developed not just for war but as personal expressions of skill, courage, and identity. While many African societies fought large-scale battles, hand-to-hand combat remained at the heart of warrior training. Whether through stick fighting, ritualised duels, or brutal striking arts, these practices forged elite fighters long before and beyond the colonial era.

Click on the links below to read more.

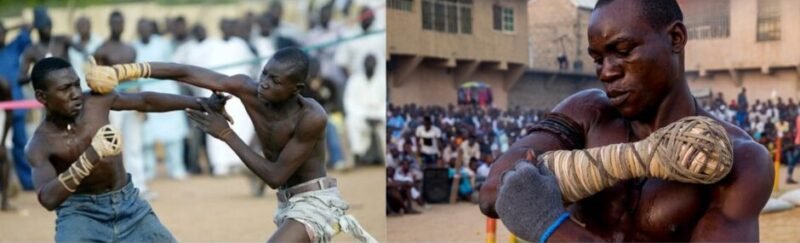

🪢🔥 Dambe: The Hausa Striking Art

Rooted in the warrior traditions of the Hausa people of West Africa—particularly Nigeria, Niger, and Chad—Dambe traces its origins to the butcher guilds, whose members were often also fighters. Dating back at least to the 18th and 19th centuries, Dambe served not only as entertainment during harvest festivals but also as a form of martial conditioning for young men preparing for war. The style revolves around a brutal one-armed striking system where the lead fist, called the “spear,” is tightly wrapped in cloth and rope, sometimes dipped in resin or ash for symbolic effect. The rear hand—“the shield”—is kept open to block or parry, while legs are used for sweeping kicks and balance disruption. Dambe matches are often short, intense bursts of violence marked by rhythmic footwork, feints, aggressive rushes, and an unspoken battle for psychological dominance. Though traditionally fought in sandpits with drums beating in the background, modern Dambe continues to evolve, preserving its gritty heritage while finding new audiences across Africa and online.

🐃🔱🛡️ Zulu Warfare: Close-Quarters Combat

The Zulu Kingdom, under Shaka Zulu, transformed regional warfare through highly disciplined military tactics, centred around the iklwa (short thrusting spear) and hand-to-hand combat techniques. Shaka’s Impi formations used the “horns of the buffalo” strategy, focusing on encirclement, shock tactics, and rapid close-quarters engagements.

The iklwa, shorter than traditional throwing spears, was designed for repeated thrusting in tight formations, ensuring higher lethality in prolonged engagements. Shaka Zulu’s reforms shifted Zulu combat from long-range skirmishing to aggressive close-quarters engagements, where warriors used shields for deflection, rapid spear thrusts, and relentless forward pressure to break enemy formations.

🥢⚔️🎯 Nguni Stick Fighting: The Zulu Warrior’s Test

Long before musket warfare, Zulu warriors sharpened their reflexes and defensive instincts through Nguni stick fighting. Fought with one stick for defence and one for attack, these contests demanded agility, timing, and nerve. The practice taught fighters how to read an opponent, maintain rhythm, and strike with precision—skills directly transferable to spear and shield combat in war.

🥁🥢🧠 Ethiopian Donga: Ritual Combat and Warrior Training

Among the Suri people of Ethiopia, Donga stick fighting served as both martial training and a rite of passage. Young men faced off in one-on-one duels, aiming to knock out their opponent with precision strikes. The emphasis on balance, endurance, and crowd judgment ensured Donga sharpened not just combat skill but mental fortitude.

👩🏿🦱⚔️🚨 The Agojie (Dahomey Amazons): Close-Quarters Specialists

Trained from youth, the Agojie excelled in hand-to-hand combat using machetes, short spears, and wrestling techniques. Their small-unit ambush tactics were supported by individual combat readiness. In battle, they overwhelmed enemies with speed, shock, and precision, proving that battlefield ferocity began with personal martial skill.

🗡️🐫🏇🏽 North African Sword Traditions

In the Maghreb and Sahel, one-on-one swordsmanship flourished. Tuareg warriors wielded the Takoba with precision and ritual significance, training on foot and horseback. Moroccan fighters mastered nimcha sabres in fast-paced duels, blending Arab and Berber techniques into fluid swordplay passed through warrior lineages.

🔗🎖️💫 Weapon Mastery and Warrior Identity

Combat tools like the Hunga Munga or improvised chain weapons demanded finesse and control. In some regions, ritualised duels determined leadership or settled disputes—showing that in African martial cultures, victory rested on honour, technique, and mastery, not just brute force.

Dambe is a traditional Nigerian combat sport rooted in the warrior culture of the Hausa people, known for its powerful strikes and ritualistic combat. Fighters use a single wrapped fist called the “spear” and a free hand for defence.

Americas (Colonial Era) 🌎🪘✊🏽

Across the plantations, quilombos, and port cities of colonial Brazil and the Caribbean, martial arts became tools of survival, identity, and rebellion. Enslaved and oppressed peoples forged combat systems in secret—hiding deadly techniques within rhythm, ritual, and movement. From the evasive kicks of Capoeira to the blade work of Tire Machèt and Esgrima Criolla, these arts evolved under watchful eyes and hostile regimes. This section explores how resistance was fought not only with fists and steel, but with rhythm, spirit, and cunning.

Capoeira 🥋🎶 🦶🏽🤸🏽♂️🔥

Click on the links below to read more.

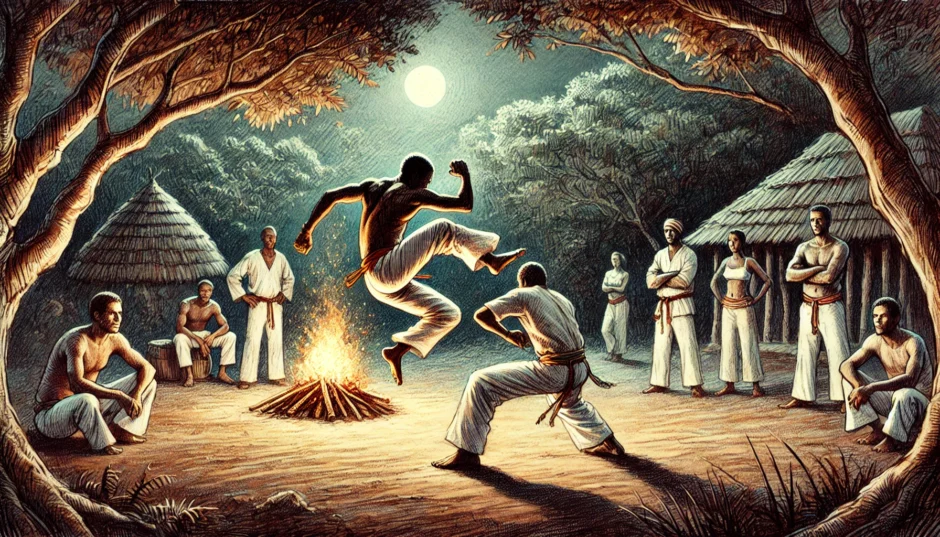

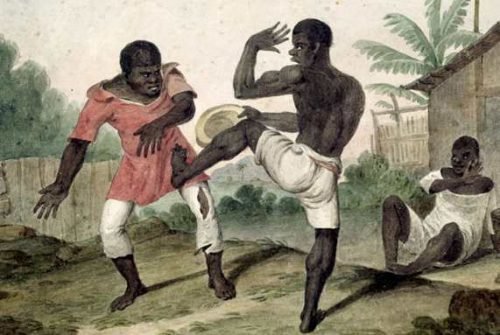

🥋🎶 🦶🏽🤸🏽♂️ Capoeira: The Martial Art of Resistance

Capoeira was born out of oppression and survival. Developed by enslaved Africans in colonial Brazil, it blended African combat dances, native Brazilian movement, and guerrilla adaptability into a disguised martial system. Combat techniques were concealed within rhythmic footwork and acrobatics, allowing practitioners to train despite Portuguese bans on martial arts. With their hands often shackled, fighters relied on low stances, evasive movement, and devastating leg strikes—turning the foot into their primary weapon.

More than performance, Capoeira became a tool of resistance. It served as an adaptable self-defence system, ambush strategy, and guerrilla warfare method used by escaped slaves (Quilombolas) against colonial forces, bounty hunters, and rival factions.

🌳🛖🤸🏽♂️ Quilombos and the Birth of Combat Capoeira

As resistance escalated in the 17th and 18th centuries, fugitive slaves established autonomous communities called quilombos, hidden deep in Brazil’s forests. The most famous, Quilombo dos Palmares, housed thousands and became a stronghold of Afro-Brazilian culture. Within these safe havens, Capoeira evolved into a battlefield art.

Quilombola warriors used Capoeira in jungle ambushes, duels, and hit-and-run strikes. Mastering deception, sweeps, and spinning kicks, they would bait enemies in close before launching explosive counterattacks. Capoeira gave these warriors the edge in tight, unpredictable engagements—turning terrain, rhythm, and movement into tactical advantages.

🧍🏾♂️🥾🌪️ Batuque and Capoeira’s Ground Game

Capoeira’s close-quarters component was shaped by Batuque, an Afro-Brazilian grappling art. Batuque emphasised leg sweeps, foot traps, and balance disruption, allowing fighters to neutralise rushing or aggressive opponents.

These techniques reinforced Capoeira’s defensive core. Fighters could bait overextension and counter with takedowns that ended fights swiftly. Together, Capoeira and Batuque formed a complete system—deceptive in form, deadly in execution.

🎵🪈🫥 The Berimbau: Rhythm, Signal, and Camouflage

Capoeira’s music was as strategic as its movement. The berimbau (a single-stringed bow instrument) acted as both rhythm and code. In rodas (circles), it dictated tempo and tactical shifts. In slave quarters and quilombos, different rhythms served as covert signals—some for sparring, others warning of nearby overseers. Drums, claps, and call-and-response songs added layers of misdirection. The dance-like appearance masked dangerous techniques while the music disguised martial intent. Through rhythm, fighters communicated, coordinated, and concealed their resistance in plain sight.

🗡️🏙️🕶️ Weapon Adaptation and Urban Survival

Though Capoeira began unarmed, it evolved to face armed threats. In Brazil’s urban centres, navalha (razor) fighting, machete evasion, and close-range defence became essential. Fighters honed spinning escapes, misdirection, and precision counter-kicks to disarm or disable blade-wielding opponents in duels, bars, and street brawls.

Even under police bans and criminalisation, Capoeira endured. These adaptations bridged the gap between tradition and survival—ensuring Capoeira remained a living, practical martial art beyond its roots in resistance.

Capoeira is a dynamic Afro-Brazilian martial art that blends combat, dance, music, and acrobatics—born from the resistance of enslaved Africans in Brazil.

Other Regional Martial Arts 🗡️🏙️🕶️

Click on the links below to read more.

🥢🇻🇪 🌀 Garrote: Venezuelan Stick-Fighting and Joint Locks

Garrote, developed in Venezuela, emphasised deflections, joint locks, and rapid strikes with short sticks, allowing fighters to close distance, disarm, and subdue opponents in one-on-one encounters. Its training focused on:

🔹 Precision footwork to manage range and angle.

🔹 Counter-striking and limb control to trap weapons or unbalance attackers.

🔹 Wrist and joint locks to neutralise aggressors quickly.

Garrote’s adaptability saw it spread to Colombia, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic, where local variants evolved to match street duels, ambush defence, and ritual displays. Though stick-based, its close-quarters mechanics mirrored unarmed grappling arts in complexity and control.

🇭🇹⚔️📜🔥 Tire Machèt: Haitian Machete Fencing

Born from resistance, Tire Machèt transformed the machete into a tool of personal combat. Drawing on African blade traditions and Spanish fencing (Destreza), it trained fighters to:

🔹 Use low stances and angular footwork to evade and strike.

🔹 Employ feints and slashing arcs to outmanoeuvre opponents.

🔹 Disarm, disable, or decapitate in single-beat counterattacks.

While pivotal during the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), Tire Machèt remained a duelling and defence system, forged in plantations, forests, and camps—where technique mattered more than firepower. Its movements remain studied today as part of Haiti’s martial heritage.

🧣🗡️👁️ Esgrima Criolla: Knife Duels and Poncho Defense

In Argentina and Uruguay, Esgrima Criolla developed as a knife-fighting system blending Spanish fencing with native combat traditions. Gauchos engaged in duelos criollos, employing:

🔹 Quick thrusts and slashes to target vital areas.

🔹 Ponchos wrapped around the forearm to trap blades, deflect slashes, and obscure movement.

🔹 Feints and close-quarters counters to neutralise opponents in confined spaces.

These duels, often governed by honour codes, demanded precision, reaction speed, and defensive trapping, making Esgrima Criolla a brutal yet refined combat system.

💃🏾🪘🕊️ Kalenda: Combat Disguised as Dance

In the Caribbean, Kalenda blended ritual, music, and stick-fighting, functioning as both a martial training system and cultural expression. Practitioners used:

🔹 Blocking and striking sequences hidden within dance movements.

🔹 Evasive footwork and deceptive feints to counter armed attacks.

🔹 Ritual combat performances to maintain martial skills under colonial rule.

Kalenda’s mechanics influenced later traditions like Trinidadian Calinda, helping preserve combat knowledge even under colonial oppression.

💃🏾🪘🕊️ Spiritual & Cultural Resilience in Combat

What unified these regional arts was a fusion of martial skill, spiritual resistance, and cultural continuity:

🔹 Drumming and rhythm enhanced timing, reflexes, and movement fluidity.

🔹 Trance states conditioned warriors for endurance, fear suppression, and heightened awareness.

🔹 Warrior spirits were invoked through dance and ritual, reinforcing mental resilience and fearlessness.

The influence of Candomblé, Santería, and Vodou in Capoeira and related arts demonstrated how spiritual resistance intertwined with combat, making these systems symbols of defiance, identity, and self-preservation.

Esgrima Criolla is a traditional knife-fighting art of the South American gauchos, using the heavy facón blade in swift, precise combat. Fighters often used a poncho on the off-hand for defence, blending practicality with duelling skill.

Legacy of Renaissance Era Combat

What Endures ⚔️ 🤼 👊🏼

The Renaissance to Early Modern Era (15th–18th Century) marked a transformative period in combat evolution, bridging the medieval age with the dawn of modern warfare. As firearms, duelling swords, and professional armies emerged, martial systems adapted rapidly, fusing traditional combat styles with innovative techniques. The integration of gunpowder weaponry, systematised training, and cross-cultural exchanges reshaped personal combat, laying the foundation for modern martial arts and military tactics. Precision, discipline, and adaptability—values refined in this era—continue to shape today’s fighters, military professionals, and combat athletes alike.

📌 Social and Cultural Identity

During this period, martial arts were deeply entwined with cultural identity, status, and honour. In Europe, fencing evolved as both a combat skill and a display of noble refinement. The Ottoman Janissaries embodied loyalty to the sultan, using combat as a reflection of spiritual and social integrity. Across Africa and Colonial America, martial arts reinforced cultural pride and personal resilience. Capoeira, born of resistance among enslaved Africans, disguised combat as dance, while Zulu warriors exemplified courage and discipline. Martial arts in this era were more than survival—they symbolised identity, empowerment, and honour in personal combat.

📌 The Formalisation and Systematisation of Martial Arts

As Renaissance thinking flourished, martial arts shifted from battlefield improvisation to codified systems. European fencing, guided by geometric principles and mathematical precision, transformed swordplay into a science of timing and angles. In Mughal India, Pehlwani wrestling thrived in akharas (training halls), blending Persian influence with indigenous grappling to create a reproducible system.

Combat manuals weren’t just instructional—they were repositories of elite martial knowledge, once passed only through direct tutelage. Texts like Fiore dei Liberi’s Fior di Battaglia or China’s Wubeizhi preserved refined techniques and helped democratise martial knowledge. As training became more structured, tools such as wooden wasters, fencing masks, and pell targets emerged, enabling live, realistic sparring. These innovations laid the groundwork for today’s sparring gear and pressure-based training models.

📌 Adaptation and Innovation in Response to Changing Warfare

As firearms gained prominence, personal combat systems evolved to address new threats. European masters like Fabris and Capo Ferro developed fencing styles that prized speed, precision, and agility, using lighter weapons like the rapier for rapid attacks and evasive footwork.