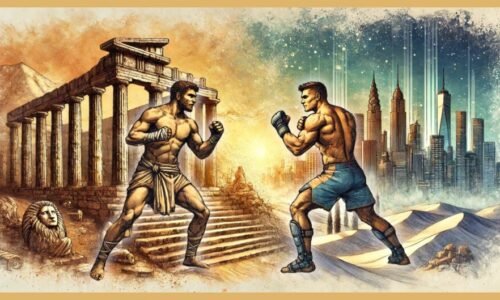

Discover how martial combat evolved through the Medieval Era, from knightly duels and battlefield grappling to the refined striking and weapon arts that shaped warriors across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Europe and much of Asia entered a period of intense political fragmentation and cultural transformation often referred to as the Middle Ages. Despite popular imagery of knights and castles, this era was also one of remarkable diversity in martial systems across the globe. From the Viking longship raids in Northern Europe to the famed samurai of Japan, and from Mamluk warriors in the Middle East to Aztec Eagle and Jaguar warriors in Mesoamerica, the medieval world teemed with unique combat traditions shaped by environment, faith, and technological progress.

⚔️🏰 Europe

As the Dark Ages gave way to Medieval Europe, Viking warriors earned a fearsome reputation with brutal raids and deadly hand-to-hand combat. Their use of the shield wall and weapon mastery reshaped European warfare. This section covers Viking tactics, weaponry, and close-quarters combat. Moving to the age of knights, we explore how these mounted and foot soldiers perfected swordsmanship, armour, and the chivalric code, blending honour with martial precision.

Click on the links below to read more.

🔥⚔️ Combat During the Dark Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Europe fractured into warring kingdoms marked by tribal conflict and shifting power. With no centralised armies or standard tactics, combat became localised, brutal, and opportunistic. Raids, skirmishes, and fortified clashes were common, as warrior bands relied on mobility, terrain, and practical warfare. Coastal towns and riverside settlements were especially exposed, lacking the defences to stop fast-moving attacks. In this chaos, a new threat emerged from the north—the Viking raiders, whose shock tactics would reshape medieval warfare.

⛵⚔️🔥 Viking Combat

Hailing from Scandinavia, Vikings mastered shock tactics, launching swift and brutal raids across Northern Europe. Their hit-and-run warfare struck fear into settlements, overwhelming defenders before they could react. As skilled seafarers, they coordinated attacks with speed and precision, making them dominant raiders and warriors.

Viking warriors adapted their weapons and tactics for both open battles and shipboard combat. Round shields allowed for formation-based tactics, while axes delivered devastating cleaving strikes capable of penetrating shields and armour. As Vikings settled in regions like the British Isles, Normandy, and Eastern Europe, their combat techniques merged with local traditions, shaping medieval European warfare in weapon craftsmanship, shield formations, and infantry tactics.

Close-quarters combat was also a Viking strength—Glíma, a grappling art dating back to pre-Viking times, enhanced their ability to fight in confined spaces. Berserkers, known for their fearless aggression and trance-like battle states, acted as shock troops, breaking enemy lines through sheer intimidation and relentless attacks. Their practical, adaptable combat approach ensured that Viking warriors remained formidable in both raids and pitched battles.

🛡️🛡️🛡️ The Shield Wall

A defining feature of medieval European combat was the use of the shield wall, a formation that emphasised collective defence and discipline over individual heroics. This tactic, popular among Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, and other Northern European warriors, involved soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder with overlapping shields, forming an impenetrable barrier against enemy charges. Unlike static formations, Viking shield walls could break apart to envelop enemies or shift into looser skirmishing lines, allowing warriors to exploit weaknesses in enemy ranks.

The origins of this tactic can be traced back to Roman legionary combat, particularly the testudo (tortoise) formation, which also relied on tight, shield-based formations for protection and advancement. While less versatile than the Roman testudo, the medieval shield wall was highly effective in static engagements and narrow terrain, allowing relatively poorly armoured troops to hold their ground against cavalry charges and heavily armoured opponents.

Its effectiveness in battle reinforced the importance of discipline, unit cohesion, and shield work in medieval martial traditions, influencing the development of infantry tactics well into the late medieval period.

🏇✝️🗡️ Knightly Combat & Chivalric

As feudal Europe developed, knights emerged as the dominant warrior class, blending battlefield supremacy with a strict martial code. Their expertise in mounted and dismounted combat, combined with mastery of swordsmanship and lance work, made them the backbone of medieval armies. More than just warriors, knights followed a chivalric code that dictated honour in combat, duty, and religious devotion—shaping everything from duelling customs to the treatment of prisoners and civilians. Religious orders like the Knights Templar fused spiritual discipline with elite martial training, reinforcing the deep link between faith and warfare.

The rise of swordsmanship schools formalised knightly combat, ensuring that techniques were preserved and refined beyond battlefield necessity. German longsword traditions and proto-Italian fencing styles focused on armoured engagements, with manuals teaching strategies for plate-armoured duels, cavalry combat, and grappling techniques suited for knights in full gear. These manuals ensured that knightly combat remained a structured, evolving martial tradition rather than a simple skill of war.

🪖 The Shift to Plate Armour

The transition from chainmail to full plate armour transformed knightly combat. Heavier protection demanded greater agility, refined footwork, and the evolution of grappling techniques such as half-swording—allowing knights to exploit gaps in armour. As traditional slashing attacks became less effective, knights adapted with precise thrusting techniques, grappling manoeuvres, and close-quarters control to dominate heavily armoured engagements.

This adaptation extended beyond the battlefield—tournament melees and formalised combat training helped maintain combat effectiveness, shaping both practical techniques and chivalric ideals. Meanwhile, battlefield innovations like the crossbow and longbow forced knights to rethink traditional tactics, leading to adaptations in cavalry formations, siege warfare, and battlefield manoeuvres. These advancements ensured that knightly combat methods remained at the forefront of European warfare.

📜🤼 Wrestling and Grappling Manuals (Fechtbücher)

Medieval fighting guides, known as Fechtbücher, were essential for training knights and soldiers, especially in German-speaking regions. Figures like Johannes Liechtenauer provided comprehensive instructions on wrestling, dagger combat, and swordplay—all vital for exploiting weaknesses in an opponent’s armour. These manuals detailed leverages, joint locks, and throws, enabling fighters to neutralise stronger or better-armed opponents with precision.

Close-quarters grappling was crucial in armoured combat, where striking was often ineffective. Techniques from these texts complemented the chivalric code’s emphasis on discipline and skill, ensuring that knights were well-rounded warriors. The 14th and 15th centuries saw these manuals refine both armed and unarmed techniques, influencing later Renaissance combat manuals and shaping medieval combat training. Their legacy remains invaluable, revealing a pragmatic and systematic approach to combat.

In medieval plate combat, fighters exploited gaps in the armour, aiming for vascular points like the neck, armpits, and inner thighs. Grappling was common, allowing them to control the opponent and drive precise thrusts into weak areas for a rapid kill despite full protection.

Middle East - 🏛️✝️⚔️☪️🕌

Martial Evolution in the Byzantine and Islamic Worlds

The Byzantine and Islamic worlds continuously adapted and innovated, shaping medieval warfare with strategic deception, superior cavalry tactics, and advanced weaponry, influencing combat doctrines across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Click on the links below to read more.

🏹 🐎✝️ Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire preserved Greco-Roman martial traditions while integrating Persian cavalry systems and steppe-nomad tactics, creating a hybridised martial doctrine rooted in both discipline and adaptability. Their elite cataphracts, heavily armoured cavalry trained for shock charges and formation-breaking, directly influenced the rise of European knights, particularly in lance warfare and armoured endurance. Infantry units, meanwhile, were drilled in close-quarters engagement, siege tactics, and urban defence, ensuring combat effectiveness across diverse terrains.

Byzantine commanders mastered psychological warfare, employing feigned retreats, ambush setups, and strategic misinformation to destabilise enemy forces before committing to direct confrontation. Their military texts—especially the Strategikon of Maurice—codified battlefield strategies, formations, and weapon applications, shaping Crusader tactics and echoing through the martial thought of medieval Europe. These manuals bridged classical combat knowledge into a new era, preserving one of history’s most adaptive and systematic martial traditions.

☪️🕌📿📜🌙 Islamic Martial Influence

Meanwhile, in Islamic territories, Arab swordsmanship absorbed influences from Greek, Persian, and Indian martial cultures, leading to the development of curved blades like the shamshir and scimitar. These weapons were designed for speed, slashing power, and mounted combat, complementing Islamic warfare’s emphasis on mobility and counterattacks. Islamic armies balanced cavalry and infantry tactics, integrating archers and spearmen for greater battlefield versatility. Military scholars such as Ibn al-Khatib documented and refined these techniques, ensuring their systematic application across different combat scenarios.

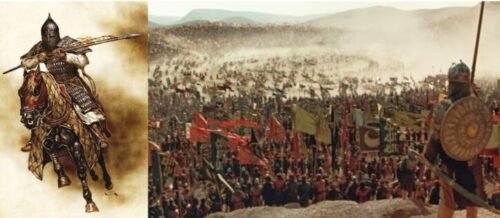

☪️🏇🗡️ The Mamluks – Elite Warrior Caste of the Islamic World

The Mamluks were not just warriors—they were an elite military caste, forged through rigorous training and battlefield mastery. Originally slave-soldiers of Turkic or Caucasian origin, they rose to dominate the military and political sphere in Egypt and the Levant. Selected and trained from a young age, they mastered cavalry tactics, excelling in mounted archery, swordsmanship, and close-quarters combat.

Their ability to fire accurately while galloping at full speed gave them a decisive edge over heavily armoured knights and infantry formations. In melee, their armoured warhorses and swift manoeuvres allowed them to dictate the flow of battle, disrupting enemy lines before they could mount an effective counterattack.

🎯 Baybars’ Battlefield Tactics

Under Sultan Baybars, their battlefield strategies evolved, incorporating feigned retreats, rapid counterattacks, and ambush tactics. At Ain Jalut (1260 CE), their strategic brilliance shattered the Mongol myth of invincibility. Using deception and precise counterattacks, they lured the Mongols into overextending before launching a decisive cavalry assault, securing the first major Mongol defeat in history.

Beyond halting the Mongol advance, the Mamluks played a crucial role in expelling the Crusaders from Outremer. Their siege of Acre (1291 CE) marked the final collapse of Christian rule in the Holy Land, as their relentless siege warfare and calculated assaults left the Crusaders with no reinforcements or retreat options. Through complex formations, relentless cavalry charges, and psychological warfare, they overwhelmed the last Crusader strongholds, cementing their legacy as one of the most skilled military elites of the medieval era.

The Mamluks, originally enslaved soldiers, rose to power in Egypt and defeated both the Mongols at Ain Jalut (1260) and the Crusaders, ending Crusader rule in the Levant. Renowned for heavy cavalry tactics, they were equally lethal in hand-to-hand combat through rigorous close-quarters training.

Asia (Mongolia, China, Japan, Southeast Asia)

⚔️ 🐉📜 ⚔️🏯 🛕

The Mongol Empire 🐎 🏹🔥🌏

Rising from the steppes, Chinggis Khan united the Mongol tribes, creating a military powerhouse built on speed, deception, and ruthless precision. This section explores the Mongols’ shock tactics, use of feigned retreats, and close-quarters combat, highlighting their weaponry and mastery of hand-to-hand techniques. Their innovations in mobility and battlefield strategy helped them conquer vast territories, leaving a lasting influence on global warfare.

Click on the links below to read more.

🌏 The Great Khan and the Rise of a Global Empire

Rising from the windswept steppes of Central Asia in the early 13th century, Temüjin united the fractured Mongol tribes through a brutal mix of diplomacy, warfare, and charisma. In 1206, after consolidating his power, he was declared Chinggis Khan—“Universal Ruler”—a title that reflected both his authority and his sweeping ambition. Bound by the Yassa (a codified law), and driven by meritocracy, loyalty, and strategic innovation, the Mongols rapidly transitioned from scattered clans into a unified war machine.

At its peak, the Mongol Empire covered over 24 million square kilometres, stretching from the Pacific Ocean to Eastern Europe—the largest contiguous land empire in human history. While known for their devastating conquests across Asia and Europe, the Mongols’ rise was equally built on close combat prowess, adaptability, and the ability to finish fights when distance closed. Behind the thunder of cavalry and siege engines lay a core of warriors trained for survival in the chaos of melee—where blades, grapples, and brutal efficiency reigned supreme.

🏹 Combat Versatility

While horse archery defined Mongol warfare, their close-combat skills were equally lethal. Warriors carried composite bows, curved sabres, lances, axes, and daggers, shifting seamlessly between ranged strikes and melee engagements.

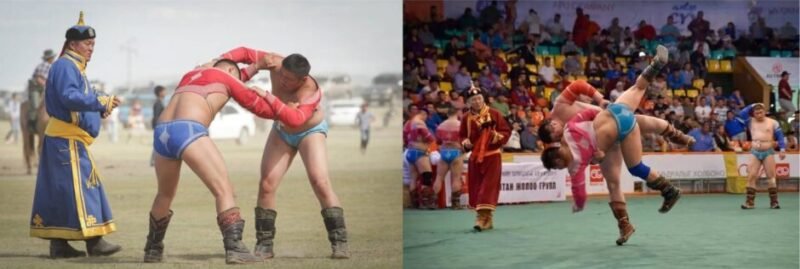

When battles descended into close quarters, Mongols employed wrestling throws, joint attacks, and finishers that exploited gaps in enemy armour. Training in Bökh (Mongol wrestling) developed strength, balance, and clinch control, translating into dominance when formations collapsed. This fusion of ranged and grappling tactics made the Mongol warrior a complete combatant, lethal in motion and dangerous in close quarters.

🤼♂️ Bökh: Wrestling at the Core of Mongol Warrior Culture

Long before the Mongols mastered sieges and global conquest, their warriors were forged through Bökh—a traditional grappling art that remains Mongolia’s national sport today. Bökh was more than physical training; it was a proving ground. Young fighters learned balance, clinch control, and takedown mastery—essentials for survival in both ritual combat and battlefield chaos.

In a world where formations collapsed and mounted combat often gave way to hand-to-hand clashes, Bökh ensured Mongol warriors could dominate up close. Fighters trained to manipulate weight, unseat riders, and finish grounded opponents, making wrestling a functional martial skill rather than ceremonial display. Victory in Bökh conferred status, honour, and often eligibility for military advancement—proving that personal combat skill was inseparable from battlefield utility.

⚔️🧠 Precision, Pressure, and Psychological Mastery

Mongol dominance was forged not by brute force, but through speed, deception, and a deep understanding of warfare psychology. Their armies operated within a precise decimal system—units of 10, 100, 1,000, and 10,000—allowing fluid battlefield coordination and decentralised control. Core tactics like the feigned retreat drew enemies into ambushes, while rotating assaults wore down resistance through sustained pressure. Communication through drums, flags, smoke signals, and mounted couriers enabled rapid shifts in momentum, often creating the illusion of omnipresence.

While famed for mobility, the Mongols also mastered siegecraft and strategic patience, employing engineers from conquered lands to build trebuchets, gunpowder weapons, and tunnel systems. They conducted sieges with surgical efficiency, favouring fear, starvation, and misinformation over prolonged conflict. These tactics weren’t just for breaking cities—they broke morale, shattered discipline, and left survivors dreading close combat with warriors who attacked without warning and finished without hesitation. It was this total warfare mindset that made the Mongol fighter lethal—on horseback, at the gate, or face-to-face in the dirt.

📜 Legacy and Influence

The Mongols transformed warfare not only through their sweeping conquests, but through the mindset they brought to combat: mobility over mass, deception over attrition, and efficiency over ornamentation. Their decentralised command structure, rotating assault tactics, and psychological warfare would influence commanders from Napoleon to Patton—but their impact ran deeper than strategy. In the chaos of collapsed formations, Mongol warriors relied on Bökh-based grappling, rapid weapon transitions, and a kill-or-be-killed mentality that shaped battlefield survival at the individual level.

Their legacy lives on in the way martial systems value adaptability, aggression, and control under pressure. From close-range wrestling to tactical feints and mental dominance, the Mongols exemplified a warrior culture where the fight was never just about strength—it was about timing, cunning, and absolute commitment to the finish.

Mongolian Bökh, a traditional form of wrestling, dates back to the time of the early steppe empires and was a core part of Mongol military training. Used to build strength, balance, and control for battlefield grappling and horse dismounts. Its legacy remains strong today, showcased every year in Mongolia’s Naadam festival as a symbol of strength and heritage.

China 🐉

Tang, Song, Yuan Dynasties (China)

Amid the golden courts of the Tang and the scholarly heights of the Song, Chinese martial arts entered a period of deep refinement and cultural elevation. At Shaolin, monks trained not only for self-defence but as guardians of sacred knowledge. As gunpowder cracked across battlefields, traditional spearwork evolved—merging ancient forms with explosive force. Guided by Taoist and Confucian ideals, martial training fused discipline, endurance, and inner balance. The result was a uniquely Chinese synthesis of spirit, strategy, and adaptability—tested in temples, courts, and on the battlefield.

Click on the links below to read more.

👊🏼 The Evolution of Chinese Martial Arts & Military Applications

Chinese martial arts, broadly known as quanfa (fist methods), became increasingly codified during this period, evolving from earlier, regional combat traditions. The Shaolin Temple played a central role, refining hand-to-hand and staff techniques that would later be adopted by military units. As standing armies expanded, long weapons like the staff and spear became vital, reinforcing the tactical value of reach and group coordination in battle.

💥 Gunpowder & Tactical Shifts

While gunpowder transformed warfare overall, its real influence on martial arts was in reshaping close-quarters combat. Early weapons like the fire lance required adaptation to multi-range fighting, combining thrusting techniques with sudden flame bursts. Once discharged—or when formations broke—fighters often reverted to hand-to-hand combat.

This shift led to greater emphasis on short blade skills, grappling, and explosive close-range tactics. Martial artists trained to close distance, neutralise threats quickly, or escape danger through precise footwork and redirection. Even with firearms present, personal combat ability remained critical.

The period also saw a rise in empty-hand techniques to counter armed opponents. Skills like disarms, joint manipulation, and balance disruption were embedded in training, allowing fighters to respond effectively when unarmed or disarmed. Techniques targeting wrists, vulnerable points, and momentum redirection proved vital in the chaos of battle—where losing a weapon could be fatal without solid hand-to-hand proficiency.

☯️ The Role of Philosophy in Martial Training

Martial systems were inseparable from Chinese philosophical thought. Taoism emphasised yielding, redirection, and the cultivation of Qi (internal energy)—influencing internal styles like Taijiquan, which relied on softness, timing, and the opponent’s intent. Confucianism, by contrast, instilled restraint, discipline, and ethical clarity, shaping fighters who possessed both technical skill and emotional control.

Together, these philosophies forged a uniquely Chinese approach to martial training—blending physical excellence with spiritual and moral development.

🗺️ The Flourishing of Chinese Martial Arts Styles

This period witnessed a surge in regional martial diversity, shaped by geography, tactics, and evolving philosophies. Martial arts expanded beyond monks and soldiers, spreading through militias, escort services (biaoju), military schools, and the civilian population.

Northern vs. Southern Chinese Styles

A major distinction emerged between Northern and Southern systems, each adapted to its local environment:

🏔️ Northern Styles (Beiquan): Originating from the flat northern plains, these styles favoured long-range techniques, fluid footwork, and high kicks. Systems like Changquan, Eagle Claw, and Bajiquan stood out for their speed, agility, and expressive forms.

🌲 Southern Styles (Nanquan): Developed in the dense, hilly South, these styles focused on short-range power, stable stances, and fast hand strikes. Traditions like Hung Gar, Wing Chun, and Choy Li Fut often evolved in clan networks or temple settings, tailored to urban conflict and tight quarters.

This split was more than geographic—it reflected a strategic divide. Northern systems emphasised mobility and reach, while Southern styles prioritised structure, centreline control, and fa jin (short explosive power). Both preserved taolu, partner drills, and classical forms, ensuring the transmission of tactics, rhythm, and combat intuition.

🧘♂️ Cultural and Spiritual Crosscurrents

Martial arts during this period became deeply intertwined with Buddhist, Daoist, and Confucian thought. While Shaolin emphasised Chan (Zen) Buddhism, other traditions like Wudang martial arts developed under Daoist influence—focusing on softness overcoming hardness, internal energy, and philosophical harmony. Styles like Xingyi Quan and Bagua Zhang emerged from this lineage, blending body mechanics, breath, and intention into close-quarters tactics.

📜 Transmission and Codification

The Ji Xiao Xin Shu (compiled by General Qi Jiguang in the 16th century) became one of the era’s most influential martial manuals—formalising soldier training while drawing on folk martial systems. Knowledge was passed down through written texts, oral tradition, and temple preservation.

Martial artists honed their craft through sparring, militia training, and challenge duels. In many towns, raised platforms known as Lei Tai hosted public fights—bare-knuckle contests with minimal rules. These matches served as proving grounds where ineffective techniques were quickly discarded, and functional combat skill was sharpened under pressure.

🧭 Legacy

The post-classical period marked a golden age of martial innovation. Though many systems remained local or family-based, the era laid the foundation for modern Chinese martial arts. Martial systems became more than just battlefield tools—they evolved into cultural artefacts, vehicles of spiritual cultivation, and lifelong paths toward discipline, identity, and personal mastery.

During the Tang and Song dynasties, Chinese martial arts absorbed influences from Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, shaping both technique and mindset. Fighters tested their skills in Lei Tai matches, aiming to knock out, submit, or throw opponents from raised platforms.

Shaolin Temple – Warrior Monks of China 🥋🥋🥋

Founded in the late 5th century CE during the Northern Wei Dynasty, the Shaolin Temple became far more than a Buddhist sanctuary—it evolved into one of the most iconic martial institutions in history. Nestled on Mount Song in Henan Province, the temple gained renown not just for spiritual cultivation, but for producing warrior-monks skilled in armed and unarmed combat. While its early years focused on meditation and monastic life, centuries of conflict, banditry, and political unrest gradually forced the monks to take up arms to defend both temple and community.

Click on the links below to read more.

🧘♂️ From Meditation to Martial Mastery

Shaolin’s martial shift is often linked to the arrival of the Indian monk Bodhidharma (Da Mo) in the early 6th century CE. Though his exact role is debated, legend credits him with introducing physical conditioning to aid meditation—laying the groundwork for martial training. These routines evolved into structured movement forms, balancing external strength with internal focus. Over time, martial practice became part of daily life, blending Buddhist principles with the hard realities of self-defence and survival.

👊🏼💥 Shaolin in Battle: From Defence to Deployment

By the Tang Dynasty (7th–10th centuries), Shaolin monks were recognised for their martial prowess, notably aiding Emperor Taizong in suppressing uprisings. This marked their transition from reclusive monks to monastic warriors, fusing spiritual devotion with battlefield skill. Training incorporated weapons like the staff (gun), sabre (dao), and spear (qiang), alongside open-hand techniques that emphasised speed, counters, and close-quarters effectiveness. The fusion of mental discipline with physical readiness made Shaolin a unique martial academy as well as a spiritual sanctuary.

🏯 The Temple as a Martial Arts Hub

Over centuries, Shaolin became a hub for martial exchange. Fighters from across China brought their regional styles to the temple, where techniques were studied, blended, and refined. This created a cross-pollination that influenced systems such as:

- Hongquan (Hung Gar) – Southern fist styles that adopted Shaolin’s low stances and powerful strikes.

- Wing Chun – A close-range fighting system said to be influenced by Shaolin-derived ideas of economy and directness.

- Northern Long Fist (Changquan) – Borrowed Shaolin’s emphasis on flexibility, speed, and acrobatic movements.

Even systems like Eagle Claw, Praying Mantis, and White Crane acknowledge Shaolin roots or were refined through interaction with Shaolin practitioners. The temple didn’t just preserve martial knowledge—it became a living repository and launchpad for innovation.

🤜🏼💥🤛🏼 Training at the Temple

Shaolin’s training was systematic and demanding. Monks drilled taolu (forms) to embed reflexes, practiced partner drills for timing and application, and underwent rigorous conditioning to develop flexibility, endurance, and striking power. These methods helped embed situational awareness, internal control, and fast response into every movement. This structured, codified approach would go on to influence not only other martial arts, but modern systems of military and athletic training.

🔥📜☯️ Legacy of Shaolin Martial Arts

Shaolin martial arts represent more than combat—they embody a way of life. Through Chan Buddhism, monks used martial practice as a vehicle for enlightenment, sharpening the body to still the mind. Though the temple was attacked, destroyed, and rebuilt multiple times, its martial legacy endured—spreading through China’s imperial military, folk styles, and eventually to the global stage. Today, Shaolin stands as a symbol of balance between spirit and steel—a living testament to the evolution of structured, spiritualised, one-on-one combat.

The Shaolin Temple, founded in 495 CE, has stood for over 1,500 years, serving as the birthplace of Shaolin Kung Fu, blending Buddhist philosophy, martial arts, and warrior training through centuries of warfare and revival.

Wudang Martial Arts 🌀

The Wudang Mountains of Hubei Province are renowned not only as a Daoist spiritual centre but as the birthplace of China’s most iconic internal martial arts. While Shaolin symbolised external or “hard” systems—built on muscular power, explosive strikes, and intense physical conditioning—Wudang stood for the internal: softness, energy cultivation (qi), and effortless redirection of force. The goal was not to overpower but to outmanoeuvre, using structure, timing, and flow.

Click on the links below to read more.

🧙♂️ Zhang Sanfeng and the Birth of Wudang Martial Arts

Wudang’s martial tradition is commonly linked to the legendary Daoist sage Zhang Sanfeng, said to have lived during the late Song or early Ming Dynasty (13th–14th century). While his historical existence is debated, his impact is not. Zhang is widely credited with founding Taijiquan (Tai Chi)—not as a meditative health practice, but as a combat art rooted in joint manipulation, internal force (fa jin), and centreline control. His teachings codified key principles still central to internal systems: stillness in motion, economy of effort, and defeating aggression through relaxation and intent.

🧘🏽♂️ Meditation or Martial Art

Despite its association with slow, graceful movement, Wudang martial arts were built for combat. Practitioners trained to survive encounters using minimal effort—relying on posture, redirection, timing, and structural alignment to neutralise stronger, faster foes. These techniques weren’t designed for the battlefield formations of Shaolin, but for personal defence, duelling, and elite close-quarters scenarios.

Soldiers, bodyguards, and even nobility embraced Wudang styles for their balance of combat utility, spiritual depth, and health longevity—a rare fusion in martial systems.

⚖️ Combat Principles with Modern Relevance

Many Wudang concepts—redirection, off-balancing, joint control, pressure point targeting—echo in modern self-defence and law enforcement techniques. The Wudang ideal of using structural intelligence to conserve energy and control aggression mirrors today’s focus on close-quarters efficiency. These methods, refined in temple halls centuries ago, still offer practical applications for real-world violence and restraint-based defence.

🥋 Key Wudang-Associated Martial Arts:

- Taijiquan (Tai Chi) – The best-known Wudang system, rooted in softness, redirection, centreline control, and internal power.

- Xingyi Quan – A more aggressive internal system, using linear attacks and coordinated power.

- Bagua Zhang – Known for its circular footwork, evasiveness, and palm strikes.

🌿 Legacy

The legacy of Wudang martial arts lies in their philosophical rebellion against brute force. Through the lens of Daoism, they taught that combat mastery could emerge from stillness, flow, and awareness—prioritising efficiency over aggression and adaptability over domination. These systems reshaped Chinese martial thinking, offering a counterpoint to Shaolin’s external intensity. Their core principles continue to influence global martial traditions today, proving that softness, when trained with precision and intent, can overcome the hardest of opponents. Wudang martial arts are not just styles—they are living expressions of balance, resilience, and strategic elegance.

The Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties marked a turning point in the evolution of Chinese martial arts, elevating them from practical defence to structured systems of personal mastery. This era laid the groundwork for a martial legacy that was not just about survival—but about refinement, adaptability, and enduring personal transformation through combat.

Japan 🇯🇵🥋⚔️🏯🎴

Samurai Traditions

As civil war fractured Japan’s provinces, the samurai emerged as disciplined warriors shaped by terrain, tradition, and spiritual resolve. From mounted archery to the katana’s deadly precision, they adapted to a shifting battlefield. Guided by Bushidō—rooted in Zen austerity and Shinto reverence—they embodied loyalty and restraint. But in the remote mountains and forests of Japan, another art took shape. Born in the shadows, shinobijutsu blended espionage, sabotage, and deception—challenging the samurai’s code from within.

Click on the links below to read more.

🗡️ Rise of the Samurai

As Japan’s feudal structure took shape, the Kamakura period (1185–1333) marked the formal rise of the samurai as a dominant warrior class. The term samurai derives from the verb saburau, meaning “to serve”—a reflection of their role as loyal retainers to powerful daimyō (regional lords). Emerging from the ashes of the Genpei War, this era saw the rise of Minamoto no Yoritomo, who was appointed Japan’s first shogun in 1192, founding the Kamakura shogunate. This marked the beginning of military governance (bakufu) and the institutionalisation of warrior rule.

🏹 The Evolution of Samurai Combat

Initially, samurai were mounted archers, dominating the battlefield with powerful kyūjutsu (archery) from horseback. But as warfare evolved, especially during Japan’s internal conflicts, samurai adapted to close-quarters combat. Techniques like kenjutsu (swordsmanship), jujutsu, and kumi-uchi (grappling in armour) became critical on the battlefield, where strikes were often ineffective against heavy armour.

Their training expanded to include yari (spear), naginata (polearm), and precision swordplay, with styles adjusted for Japan’s varied terrain and tactical needs. Armour systems such as ō-yoroi and dō-maru reflected the evolving balance between protection and mobility, ensuring readiness for cavalry charges, duels, and melee formations.

📜 The Tale of the Heike – War, Honour, and Cultural Memory

This transformative period is immortalised in The Tale of the Heike, a dramatic epic recounting the Genpei War between the Taira and Minamoto clans. Passed down through oral recitation, it captures the samurai’s early ideals: honour, loyalty, impermanence (mujō), and noble death. The Heike is filled with vivid accounts of heroic archery duels, mounted swordplay, and personal acts of valour—offering a glimpse into the emerging samurai identity where combat was both practical and poetic.

These stories did more than entertain—they shaped the samurai mindset for generations, reinforcing the concept of the lone warrior whose worth was measured not just by victory, but by how they faced defeat. In many ways, The Tale of the Heike became the spiritual blueprint for Bushidō, long before it was formally codified.

⚔️ Samurai Innovation Against the Mongol Threat

During the Mongol invasions of 1274 and 1281, samurai were confronted with unfamiliar mass tactics, explosive weapons, and coordinated naval assaults. Forced to adapt, they engaged in coastal defence, boarding actions, and close-quarters skirmishes, proving their ability to respond flexibly to evolving threats. These encounters reinforced the value of individual initiative, mental resilience, and versatile combat skill—traits that remained central to the samurai ethos.

Sidenote: The Mongol invasions, led by Kublai Khan, posed an existential threat to Japan. But on both occasions—1274 and 1281—their massive fleets were shattered by violent typhoons, abruptly ending the campaigns. These storms were later mythologised as kamikaze, or “divine winds,” believed to have been sent by the gods to shield the nation from foreign conquest. The legend would echo centuries later in Japan’s wartime psyche, symbolising protection through sacrifice and destiny.

Out of the Shadows - Shinobijutsu in Feudal Japan 🥷🤫🗡️

In the shadowed valleys of Iga and Kōga, far from courtly rituals and battlefield glory, a different kind of warrior took shape. As samurai clashed in open combat, the shinobi moved unseen—masters of stealth, sabotage, and psychological warfare. Born from fractured provinces and shifting alliances, shinobijutsu offered a counterpoint to honour-bound tradition, favouring deception over duels. This section explores the roots of Japan’s shadow warriors—their tools, tactics, and the fear they wielded as effectively as any blade.

Click on the links below to read more.

🥷 Origins and Role in Feudal Warfare

During the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Muromachi (1336–1573) periods, shinobijutsu—the art of stealth, infiltration, and irregular warfare—emerged as a practical response to Japan’s fragmented political landscape. Rooted in the remote, mountainous provinces of Iga and Kōga, shinobi agents provided an essential alternative to the honour-bound warfare of the samurai. They served as scouts, saboteurs, messengers, and assassins, specialising in tasks that required subterfuge over open combat. Their value lay in their ability to gather intelligence, disrupt enemy operations, and operate unseen.

🌲🏔️☸️ Development and Influences

Shinobi skills were likely passed down within families and tight-knit local networks, blending hunter-tracker techniques, rural survival skills, and the practical needs of borderland warfare. While often associated with yamabushi (mountain ascetics) and the esoteric practices of Shugendō, these links remain debated. However, the shared terrain, secrecy, and anti-authoritarian ethos suggest at least cultural overlap. Shinobi were also connected to Amida Buddhist movements, particularly through alliances with the Ikkō-Ikki—militant temple communities that resisted central samurai control. In these uprisings, shinobi were known to assist in defending fortified temples and coordinating ambushes.

Claims of influence from Chinese military strategy, such as Sun Tzu’s Art of War or figures like Prince Shōtoku, are largely retrospective and lack direct historical evidence. While continental ideas eventually entered Japanese military thought, shinobijutsu appears to have developed organically, shaped by terrain, necessity, and local resistance, rather than by foreign texts or imperial models.

🗡️ Weapons and Fighting Style

Shinobi favoured tools and tactics suited to speed, deception, and quiet execution rather than prolonged duels or battlefield confrontation. Their arsenal typically included:

- Concealed blades (tantō, kaiken) for close quarters

- Throwing weapons (shuriken, metsubushi) to distract or disable

- Climbing tools (grappling hooks, rope ladders)

- Fire devices and smokescreens for confusion and escape

- Disguises and portable kits tailored for sabotage or infiltration

In combat, they emphasised fast strikes, joint manipulation, low stances, and evasive footwork, prioritising escape over engagement. Their unarmed skills were likely adapted from local jujutsu traditions, focused on disabling opponents quickly and quietly.

👁️ The Use of Myth and Fear

While shinobi themselves were not mystical, they became increasingly associated with supernatural figures such as Tengu—mountain spirits known for martial prowess and mischief. Rather than resist these associations, some shinobi groups embraced the myth, using it as a form of psychological warfare. Enemies who believed they faced sorcerers or ghost-like assassins were more prone to panic, paranoia, and collapse before a fight even began. In this way, fear became a tactical asset—reinforcing the shinobi’s advantage through rumour and theatrical deception.

🔥 Legacy at the Close of the Muromachi Era

By the end of the Muromachi period, shinobijutsu had become a recognised, if secretive, discipline—tied not to myth, but to pragmatism, adaptability, and strategic necessity. Though later eras would blur fact with fiction, the early shinobi were not magical warriors, but highly trained specialists who navigated the shadows of Japan’s feudal conflicts. Their skills were a response to political uncertainty and military imbalance—an enduring example of how warfare evolves beyond the battlefield.

The Shinobi emerged during Japan’s turbulent early feudal periods, developing skills in espionage, infiltration, and sabotage. By the Muromachi era (1336–1573), they operated as specialised agents for samurai lords, gathering intelligence, disrupting enemy forces, and conducting covert operations behind the lines.

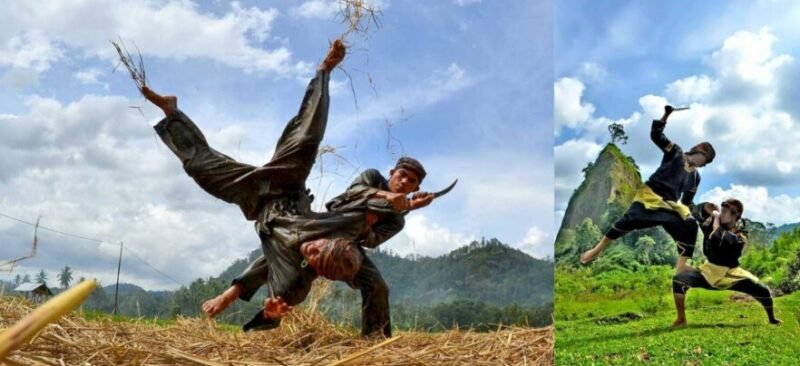

Southeast Asian Systems 🌏

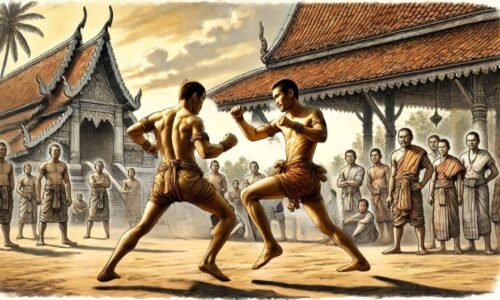

In the humid jungles and coastal kingdoms of Southeast Asia, warfare demanded speed, precision, and adaptability. Martial systems like Muay Boran, Bokator, and Silat fused Indian striking arts and Chinese strategy with local tactics shaped by terrain and trade. Warriors trained for ambush, jungle combat, and shipboard skirmishes—using curved blades, joint locks, and deception to overwhelm their foes. This section explores how these systems adapted to tropical environments, each leaving a lasting impact on both regional and modern combat.

Click on the links below to read more.

📜⚔️🔥 Origins & Influences

Martial systems like Muay Boran (Thailand), Bokator (Cambodia), and Silat (Indonesia/Malaysia) trace their roots to Indian and Chinese martial traditions, transmitted through ancient trade routes and religious exchange. From Kalaripayattu, they absorbed striking forms, pressure-point strikes, and the use of war elephants. From China came tactical footwork, deception, and adaptability—principles that fused seamlessly with Southeast Asia’s dynamic terrain and political volatility.

These arts evolved in tropical environments, giving rise to specialised striking, joint manipulation, and weapon techniques tailored for both open warfare and ambush scenarios. Warriors were trained to fight in dense jungle, urban settlements, and on shifting coastal battlefields—adapting tactics to their fluid surroundings.

🌴🌳🌿 Tactics of Terrain – Jungle and Maritime Warfare

Southeast Asia’s geography—dense forests, river networks, and sprawling coastlines—demanded ambush, feint, and close-quarters efficiency. Warriors excelled in hit-and-run tactics, stealth manoeuvres, and sudden engagements, often disorienting better-armoured or more numerous foes.

Kingdoms like Srivijaya and Majapahit built empires on naval supremacy. Their warriors honed their skills in ship-to-ship combat, using short weapons and dirty boxing in cramped quarters. These tactics demanded extreme precision, balance, and the ability to grapple, strike, or kill in a single motion—all under chaotic, wet, and shifting conditions.

⚔️ Weapons of the Region – Precision and Stealth

Weapons like the kris (wavy dagger) and karambit (curved claw-like blade) became iconic across the region. Designed for slashing, trapping, and fast counterstrikes, these blades reflected the Southeast Asian focus on speed, unpredictability, and anatomical targeting. Both were ideal for stealth operations, assassinations, or use in confined environments.

The influence of Indian warfare also introduced war elephants—platforms for archers and spear fighters. While visually dramatic, their use required strategic synergy with foot soldiers, especially in thick jungle or siege conditions where melee tactics remained vital.

🤜Combat Systems and Hand-to-Hand Specialisation

Southeast Asian warriors often trained in short-range striking and grappling, refining their skill sets for real-world conflict. Silat, in particular, focused on fluid transitions, deception, joint control, and off-balancing, making it highly effective in both armed and unarmed duels. Meanwhile, Filipino arts like Panantukan (“dirty boxing”) taught elbow strikes, limb destruction, and foot traps—ideal for both battlefield and street-level encounters.

This combination of blade work and empty-hand combat ensured that even when disarmed, a Southeast Asian fighter remained dangerous, capable of disabling or neutralising an opponent swiftly and efficiently.

🧘🏽♂️ Spiritual Discipline and Warrior Identity

Many systems, especially Silat, fused martial training with spiritual disciplines, incorporating breath control, meditation, ritual movements, and belief in inner energy (semangat or tenaga dalam). Combat was not only physical—it was about mental clarity, deception, and flow, with practitioners taught to control both opponents and their own emotions. These traditions paralleled codes like Bushidō, instilling self-mastery, honour, and resilience.

Pencak Silat, a martial art of Indonesia and Southeast Asia, blends indigenous techniques with Indian, Chinese, and Islamic influences. It evolved for battlefield use, combining strikes, grappling, and weapons, and remains a key part of regional cultural identity.

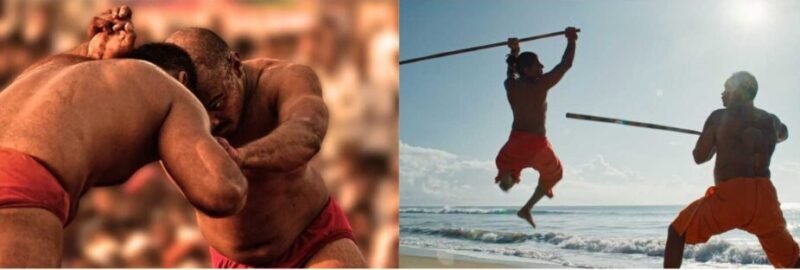

India 🕉️

Martial Systems of the Post-Classical Era

Across the temples, forests, and training grounds of the Indian subcontinent, martial traditions flourished as a fusion of combat, discipline, and spiritual depth. Systems like Kalaripayattu, Malla-Yuddha, and Silambam evolved through dynastic warfare, religious philosophy, and centuries of refinement. From the whip-like urumi to the ritual duels of the Rajputs and the guerrilla tactics of the Marathas, India’s martial arts forged warriors who balanced precision with purpose—blending battlefield skill with inner mastery.

Click on the links below to read more.

⚔️ Regional Evolution and Influence of Kalaripayattu

Throughout India’s history, regional kingdoms such as the Chola, Chera, and Pandya dynasties refined Kalaripayattu, adapting its techniques and weapons—including the urumi (flexible sword)—to shifting political landscapes. Beyond swordplay and staff combat, warriors incorporated animal-inspired movements (tiger, snake, eagle styles), emphasising adaptability and fluidity in battle.

The urumi, known for its unpredictable whipping strikes and multi-target engagement, was favoured for crowd control and rapid offensive attacks. Trained fighters relied on close-quarters agility and deceptive movement to counter heavily armed opponents.

Kalaripayattu’s influence extended beyond India, shaping Silat in Southeast Asia and possibly Chinese martial arts through Buddhist monk exchanges. Trade routes and religious missions facilitated the spread of combat techniques and philosophical principles, allowing Indian martial knowledge to merge with regional fighting traditions.

⚔️📿🌿 The Spiritual and Healing Aspects of Kalaripayattu

Spiritual and healing traditions remained central to Kalaripayattu, drawing from Hindu and Buddhist practices. Mantras, meditation, and ritualistic training cultivated mental resilience and combat focus, ensuring warriors remained calm under pressure. Practitioners also studied Ayurvedic healing and vital point strikes (marmas), blending combat knowledge with medical treatment.

The Dhanurveda, an ancient text on martial arts and archery, codified weapon and unarmed combat principles, shaping structured training methodologies. The tradition of martial festivals and Akhara training grounds institutionalised combat practice, ensuring a systematic approach to warrior training.

Beyond warfare, Kalaripayattu’s movements influenced Kerala’s ritual combat dances, such as Theyyam and Kathakali, where martial postures and weapon demonstrations became part of sacred performances. Over time, its techniques also influenced Tamil Nadu’s Silambam, preserving India’s oldest martial traditions and reinforcing its enduring legacy.

🤼♂️ Malla-Yuddha - Evolution

Throughout this era, Malla-Yuddha remained a foundational discipline within India’s martial culture, particularly among Kshatriya warriors and in traditional akhara training grounds. While it did not undergo major transformation during this period, it continued to serve as a core method for developing strength, balance, and close-quarters control, complementing armed systems like Kalaripayattu, Rajput swordsmanship, and Maratha close-combat tactics. Practiced alongside striking and weapon drills, Malla-Yuddha reinforced the grappling instincts essential to surviving chaotic, body-to-body encounters. Its structured techniques and emphasis on leverage laid the foundation for the hybrid Pehlwani system that would emerge under Persian influence during the Mughal era.

🌀 Silambam – The Art of the Staff Fighter

Developed in Tamil Nadu, Silambam is one of India’s oldest and most practical weapon-based martial arts. Centred around the long bamboo staff (silambam), this system emphasises range control, speed, and angular footwork, making it ideal for one-on-one encounters. Practitioners were trained to move with fluid steps called kaaladi, allowing them to strike, evade, and counter with precision.

Though often associated with battlefield training, Silambam’s real strength was its adaptability in duels, street defence, and royal guard training. Fighters progressed from the staff to short sticks, sickles, and deer horns (māl yutham)—each requiring mastery of timing and close-quarters reflexes. Sparring was fast-paced and technical, prioritising control over brute force.

Training also incorporated breath control, posture drills, and spinning routines that developed agility and mental clarity. Silambam’s emphasis on rhythm and weapon flow later influenced both Kalaripayattu’s stick work and regional performance arts, ensuring its preservation even during colonial bans. Today, Silambam survives as both a combat art and cultural tradition—one that forged warriors through simplicity, speed, and technical brilliance.

🛡️ Rajput Warrior Traditions

The Rajputs of northwestern India embodied a warrior code (kshatriya dharma) centred on honour, loyalty, and lineage. Known for their preference for frontal combat and last stands, they trained in sword-and-shield fighting, longbow archery, and dagger techniques like the use of the katar. Rajput warriors valued ritual combat and personal bravery over tactical deception, with martial skill tied closely to social identity and status.

While influenced by Persian and Mughal systems over time, the Rajputs maintained a distinct emphasis on close-range skill and ceremonial warrior ethos, favouring structured duels and stylised combat challenges over battlefield cunning. Their traditions reinforced the idea of combat as both duty and display, preserving India’s martial codes through regional dynasties.

🐅 The Maratha Confederacy

Emerging from western India, the Marathas developed a style of warfare built on speed, unpredictability, and individual initiative. Fighters were trained in ambush tactics, hit-and-run engagements, and rough terrain combat, often using the pata (gauntlet sword) and katar in confined or chaotic environments. These weapons favoured fast, penetrating strikes and guarded offence, allowing fighters to close distance quickly and end fights decisively.

Beyond tactics, Maratha combat drew spiritual resilience from the Bhakti movement and martial ascetics like the Nagas, whose discipline, austerity, and psychological conditioning helped shape warrior identity. These fighters cultivated mental toughness alongside technical skill, forging a martial path rooted in both precision and perseverance.

In post-classical India, martial arts like Malla Yuddha and Silambam continued to evolve, preserving indigenous combat traditions. Wrestling, weapon arts, and battlefield techniques remained central to warrior training across regions and dynasties.

Persia 🦁⚔️📜🔥☀️

In the heartlands of Persia, martial training was never just about combat—it was a path to strength, virtue, and spiritual harmony. From the mounted warriors of the Parthians to the ritual discipline of the Sassanids, a legacy of wrestling, strength training, and moral philosophy took shape. Under Islamic influence, this evolved into Varzesh-e Pahlavani—a warrior tradition where combat met mysticism, and the fighter became a symbol of both power and humility.

Click on the links below to read more.

⚔️ The Evolution of a Warrior Tradition

The development of Varzesh-e Bastani and Pahlavani was not the product of a single empire, but the result of a long martial lineage spanning centuries. stretching back to the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BCE) to the Parthians (247 BCE–224 CE), these eras laid the foundations through their focus on cavalry warfare, physical conditioning, and wrestling. The Sassanids dynasty (224–651 CE) built upon this with greater systematisation, infusing martial training with Zoroastrian ethics and ritual discipline. Under the Islamic Golden Age, these practices evolved into Pahlavani—a synthesis of combat, spirituality, and moral philosophy shaped by Sufi mysticism. Each era left its mark, forging a unique warrior tradition that balanced physical strength with inner virtue.

🤼 Pahlavani – Persian Wrestling

As Persia transitioned into the Islamic era, the practical grappling art of koshti evolved into Pahlavani—a ceremonial form of wrestling deeply embedded in Persian culture and Sufi values. Practised in the sacred Zurkhaneh (“House of Strength”), Pahlavani was not merely about winning a contest—it was about embodying moral integrity. The Pahlavan became a symbolic figure: a warrior-saint defined by humility, strength, and community leadership.

Combat was ritualised, accompanied by music and spiritual recitations, reinforcing values of honour and self-discipline. The grappling techniques remained effective and combat-relevant, but they were performed as part of a moral and spiritual exercise. This ceremonial evolution preserved Persian wrestling as a living symbol of inner and outer mastery.

🤸♂️💪🏽🔥🏋️♂️ Varzesh-e Bastani – Strength and Spiritual Training

Rooted in the same Zurkhaneh tradition, Varzesh-e Bastani (“Ancient Sport”) served as the physical and spiritual conditioning system that supported combat arts like Pahlavani. Drawing from Zoroastrian ideals and later Islamic mysticism, this discipline included training with meel (wooden clubs), sang (stone shields), and dynamic calisthenics to forge both physical power and mental clarity.

Unlike direct combat, Varzesh-e Bastani focused on developing the body and aligning the spirit, creating warriors who were not only strong, but principled and composed. Ritual movement, music, and spiritual recitation created a meditative rhythm, turning physical exertion into a path of cultural identity and inner harmony.

Together with Pahlavani, this system formed a uniquely Persian fusion of warrior training, moral education, and spiritual expression—a tradition that endures today as both national pride and living martial heritage.

Pahlevani and Zoorkhaneh rituals, developed in ancient Persia, integrated strength training, martial techniques, and spiritual discipline to prepare warriors. They preserved core elements of Persian martial culture from the Achaemenid and Islamic periods into the modern era.

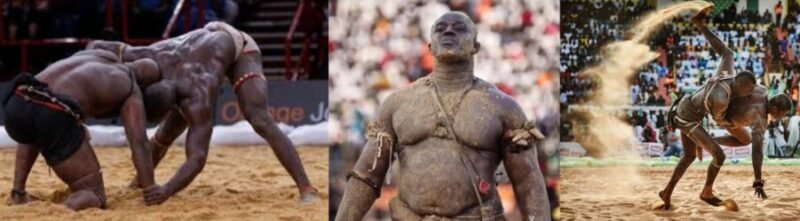

Africa 🌍

Across Africa’s vast plains, highlands, and river valleys, warrior traditions took shape through terrain, tribal warfare, and cultural ritual. From Ethiopia’s shotel-wielding swordsmen to the grapplers of West Africa, combat emphasised agility, deception, and close-quarters precision. Stick fighting, wrestling, and curved blades formed the backbone of regional systems—each rooted in survival, ceremony, and identity. This section explores how Africa’s martial arts evolved through war, culture, and legacy.

Click on the links below to read more.

⚔️ The Shotel and Ethiopian Combat Tactics

Ethiopian warriors wielded the shotel, a uniquely curved sword designed to hook around shields and strike exposed areas. Its inward curve allowed fighters to bypass defences and attack from deceptive angles, making it highly effective in close-quarters combat. Often paired with a small round shield, warriors relied on feints, counters, and precise deflections to control engagements. Indigenous fencing traditions developed around the shotel emphasised mobility, agility, and unpredictability.

Training in Donga (stick fighting) sharpened footwork, timing, and defensive manoeuvres—skills directly transferable to swordplay. Against spears and longer weapons, Ethiopian fighters used sidesteps, inside-line attacks, and hooking strikes, exploiting the shotel’s curvature to disrupt opponents and dominate confined terrain.

✨ Spiritual & Cultural Influences on Ethiopian Warfare

Ethiopian combat traditions evolved alongside challenging terrain and diverse cultural influences. Tactics prioritised speed, deception, and counter-striking, aligning with the shotel’s agility. Warriors often trained with the aid of ritual blessings, talismans, and traditional medicinal practices, reinforcing mental resilience and spiritual protection in battle.

Encounters with Arab, Nubian, and Ottoman forces introduced new shield types and defensive techniques, further refining Ethiopia’s close-combat systems. Today, the legacy of the shotel endures in ceremonial displays and historical reenactments, preserving its martial and cultural identity.

🛡️ West African Combat Traditions

While the Mali and Songhai empires are often remembered for cavalry and large-scale tactics, their warriors also relied heavily on short-range melee skills. Infantry commonly fought with spears, short swords, and shields, demanding strong personal control, footwork, and timing. In forested and riverine regions, ambushes and hit-and-run attacks required tight-angle combat and quick engagements, favouring warriors skilled in striking and grappling at close range.

🤼♂️ Laamb and the Legacy of West African Wrestling

The roots of Laamb (Senegalese wrestling) trace back to this era, developing alongside other West African wrestling traditions in Mali, Songhai, Ghana, and Nigeria. Warriors trained in Laamb-style wrestling to develop grappling strength, balance, and takedown skills, essential for close-quarters combat when disarmed or engaged in melee battles. The sport also played a cultural role, used in combat training, spiritual rites, and displays of strength to establish social status and warrior identity.

While Laamb would not become Senegal’s premier combat sport until much later, its early forms laid the foundation for its lasting influence in West African martial culture. The preservation of these traditions ensured that Laamb evolved over centuries, blending rituals, music, and combat techniques into a distinctive martial art.

🌀 Engolo

Further south, among the Bantu-speaking peoples of Angola, a ritualised combat game known as Engolo developed. Characterised by low stances, evasive movements, and inverted kicks, Engolo emphasised agility, deception, and physical prowess rather than structured combat training.

While some of its techniques later influenced the development of Capoeira in Brazil, claims that Engolo functioned as a full martial system are disputed. Current evidence suggests it served more as a ceremonial and athletic practice, blending symbolic competition with displays of skill rather than preparing warriors for actual battlefield conditions.

🏜️ 🤼♂️ Nubian Wrestling – Grappling Tradition of the Nile

In the northeast, Nubian wrestling continued to thrive among tribes in what is now Sudan. Depicted as early as the Egyptian Middle Kingdom, this grappling art was deeply rooted in ritual and community life, often performed during festivals, rites of passage, and tribal gatherings. Fighters trained for grip control, positional dominance, and powerful throws, developing the physical resilience needed for tribal warfare and the endurance demanded by desert campaigns.

More than a method of combat, it was a tool of social cohesion, reinforcing strength, discipline, and status among warrior-age males. In an age defined by intertribal conflict and shifting alliances, Nubian wrestling preserved a link to ancient martial identity while continuing to evolve as a practical system of close-quarters combat in a changing African landscape.

Laamb, practised in West Africa from at least the 13th century, served as warrior training among the Wolof and Serer peoples. It built strength, endurance, and grappling skills essential for combat before evolving into a cultural sport.

Americas (Pre-Columbian) 🪶🌞🦅🗡️🪅

In the temples and highlands of the Americas, warrior cultures fused combat with ritual, identity, and cosmic purpose. Aztec and Mayan fighters trained not just to kill, but to capture—masters of close-quarters control, wielding obsidian blades with precision and restraint. In the Andes, Incan warriors adapted to steep terrain with clubs, slings, and formation-breaking agility. Across both worlds, warfare was sacred—a discipline of body, spirit, and status where mastery meant survival, honour, and eternal remembrance.

Click on the links below to read more.

🛡️ Aztec and Mayan Combat – Ritual, Technique, and Elite Warriors

Aztec and Mayan warrior societies placed immense value on personal combat prowess, particularly among elite ranks like the Eagle and Jaguar warriors. These fighters trained in disciplined formations, yet individual skill remained central, as battles often aimed not to kill, but to capture opponents alive for ritual sacrifice. The macuahuitl—a wooden club embedded with obsidian blades—was their weapon of choice. Its slashing power was capable of severing limbs, but in many encounters, warriors were trained to disable without killing, emphasising precision strikes and control over brute lethality.

Jaguar and Eagle warriors advanced in status through battlefield achievements, including hand-to-hand duels and ritual combat. The two-handed macuahuitl offered devastating power, while lighter versions allowed for faster, more fluid combinations in close quarters. Obsidian daggers, atlatls, and even blowguns were employed in ambushes or jungle skirmishes, where stealth and accuracy replaced open-field engagement. Shields (chimalli) were used not only for protection but as status markers, with warriors learning to parry, angle, and counter while closing distance.

🌸 The Flower Wars

One of the most distinctive features of Aztec martial culture was the Flower War (xochiyaoyotl)—a ritualised form of battle where the objective was not conquest, but capturing enemies alive for ceremonial sacrifice. These staged engagements served as a proving ground for elite warriors, refining their restraint, tactical precision, and psychological dominance. Unlike chaotic battlefield skirmishes, the Flower Wars followed predictable formats, allowing fighters to showcase personal skill, composure, and technique. In many ways, they functioned as a martial pressure test—part combat training, part spiritual obligation, reinforcing the link between ritual combat and warrior development.

🏔️ 🏔️ 🏔️ Andean Martial Culture – The Inca Approach to Close Combat

While the Inca are often remembered for logistical brilliance and highland strategy, their warriors also developed effective close-range techniques suited to the mountainous terrain. The huaraca (sling) was used at mid-range, but once in melee, Incan fighters relied on stone-headed clubs, axes, and short spears, often fighting in dense, uneven terrain that required agility and strength in tight quarters. The Tumi, a ceremonial axe, may have had symbolic uses, but its form suggests it could also be employed in combat at close range, especially for finishing strikes.

The bolas—a throwing weapon designed to entangle—created openings for warriors to rush in and finish opponents with blunt or edged weapons, demanding timing and coordination in one-on-one engagements. Though often organised in formations, Incan warriors were trained to fight independently when necessary, using quick footwork, momentum control, and environment-based positioning in steep, narrow paths and cliffside trails. Combat was often psychological as well—war cries, drumming, and ritual noise disrupted enemies, while reinforcing personal ferocity and confidence in battle.

🌀🦅🗡️ Ritual Combat and the Spiritual Warrior Ethos

Across both Mesoamerican and Andean cultures, combat was deeply entwined with spiritual belief, discipline, and warrior identity. The Aztec concept of warfare as a sacred duty elevated the importance of restraint, honour, and technique—qualities essential to capturing enemies rather than killing them outright. The structured progression of Aztec warriors, from novices to elite orders, reflects a proto-martial art system, where mastery of weapons, tactics, and composure defined one’s role in society.

Similarly, Incan warriors trained under a state-run military system but were shaped by ritual, terrain, and precision, making them formidable in close-quarters combat despite lacking the metallurgical weapons of Old World counterparts. In both civilisations, the focus on discipline, adaptability, and close-range control underscores their place in the broader evolution of martial techniques.

The warrior spirit of South American civilisations like the Aztec, Inca, and Maya still echoes among fighters today, particularly in Mexico. Traditions of resilience, sacrifice, and ritual combat — seen in practices like the Aztec Flower Wars — continue to inspire modern fighters who embody the same fierce pride and fighting spirit.

Legacy of Medieval Era Combat

What Endures ⚔️ 🤼 👊🏼

The Post-Classical / Medieval Era (5th–15th Century) was a period of martial transformation, laying the foundation for many of the principles that continue to shape modern combat techniques and military strategies. Key innovations from this era—psychological warfare, adaptability in combat, codification of techniques, and warrior codes—remain influential across both military and martial arts systems today.

📌 Deception as a Fighting Mindset

In the medieval era, combat extended beyond brute strength—the mind became a weapon. Across cultures, warriors learned that misdirection, stealth, and information could turn the tide of battle. In Japan, shinobi operated not just as saboteurs but as intelligence gatherers—observing enemy habits, studying weaknesses, and striking where it hurt most. These tactics filtered into personal combat, influencing duelling strategies, feints, and timing-based counters.

The Byzantines, known for military cunning, relied on spies, reconnaissance, and disinformation to weaken opponents before any clash. This same mentality lives on today in fighters who analyse opponents’ footage, map out flaws, and craft gameplans to win before the first blow lands. Whether on a battlefield or in the ring, deception and intelligence became inseparable from victory.

📌 Intimidation and Psychological Warfare

Not all battles are fought with blades. Many are won by breaking the opponent’s will. The Aztecs used war drums, ritual chants, and elaborate body paint to overwhelm their enemies before a fight began—projecting power to create doubt. This visual and auditory dominance finds a modern echo in walkout music, body paint, and fighter personas, all designed to gain a psychological edge before the first strike.

The Viking berserkers weaponised unpredictability, entering battle in trance-like states of rage to intimidate and disorient their foes. Today’s fighters still train for emotional control, mental resilience, and harnessed aggression—ensuring they don’t just look dangerous, but are ready to dominate mentally as well as physically.

📌 Tactical Adaptability and Versatility

Medieval fighters trained across multiple weapons, stances, and combat environments. Japanese samurai were versed in archery, sword, spear, and grappling; European knights mastered mounted and dismounted fighting.

This cross-training mindset lives on in arts like jujutsu, kampfringen, Silambam, Krav Maga, and MMA. These systems value fluidity, versatility, and environmental awareness over rigid form.

📌 War in Two Dimensions: Collective Formations & Personal Tactics

Medieval warfare operated on two interlocking levels—macro strategy, involving formations and battlefield positioning, and micro tactics, focused on the skills of individual fighters. Formations like the shield wall and phalanx required not just discipline but intimate coordination, where a single lapse could collapse the line. This reinforced the need for precise footwork, tight weapon control, and spatial awareness—all critical in modern individual combat training.

While armies moved as units, success often hinged on how well each warrior could exploit gaps or adapt under pressure. Techniques like half-swording in European longsword combat or kumi-uchi in Japanese armour grappling evolved to function in tight ranks.

Even today, military and police forces use this dual-level thinking. Riot units still apply medieval shield principles, while CQB training hones individual tactics for room entry, disarms, and grappling under stress. Tactical cohesion and personal skill remain inseparable.

📌 Codification of Combat Techniques & Transmission of Knowledge

The medieval period saw combat shift from instinctive skill to codified systems of martial knowledge. In Europe, Fechtbücher (fight manuals) documented swordsmanship, grappling, and armoured combat, ensuring techniques could be preserved, taught, and refined.

The Crusades and trade networks like the Silk Road expanded the exchange of martial ideas—soldiers, monks, and travellers cross-pollinated tactics, weapons, and philosophies.

Today’s military manuals, martial arts syllabi, and training curriculums continue this legacy. Documentation became a way to preserve, analyse, and refine systems in a world of shifting threats.

📌 Shock Tactics & Hit-and-Run Warfare

Medieval warfare saw the rise of shock tactics and mobile ambush warfare. Vikings struck with sudden force, Mongols mastered feigned retreats and flanking raids, and Mamluks used trap-based counters to overwhelm.

These strategies became doctrine, not just tactics. Modern special forces, guerrilla units, and even MMA fighters use flurries, feints, and mobility to destabilise. The principles of timing, surprise, and aggression remain unchanged.

📌 Warrior Codes & Ethics

This era introduced formal warrior codes—Bushidō, Hwa Rang Do, and chivalry—which bound warriors to honour, courage, and discipline. These codes created not only better soldiers, but better human beings.

Their legacy endures in military ethics, rules of engagement, and combat sport etiquette. Fighters today still bow, touch gloves, and train with humility, echoing these ancient moral systems. Though less recorded, female warriors played powerful roles—from Norse shieldmaidens to onna-bugeisha in Japan. Their presence reinforces that martial identity was shaped by purpose, not just gender.

📌 Combat as Spiritual Discipline

Combat wasn’t just survival—it became a spiritual path. The Shaolin Temple fused martial training with Zen and meditation, while Wudang monks cultivated internal power through softness and flow.

In Persia, Varzesh-e Pahlavani merged wrestling, calisthenics, and Sufi ethics, crafting complete warriors of body, mind, and spirit.

Even today, martial arts are used to build mental clarity, inner balance, and discipline far beyond the mat. Techniques like breathwork, mantras, and visualisation helped early fighters override fear. These ancient methods predate modern stress inoculation training, showing that the mind has always been a combat tool.

📌 Weapons and Armour

The arms race between weaponry and protection drove innovation. Plate armour made grappling and joint targeting essential. Curved blades like the shotel and macuahuitl countered shields or armour. In the Andes, the Inca used slings and clubs ideal for mountainous terrain.

Function shaped form, and every tool reflected its environmental and tactical purpose. That same thinking fuels modern gear design, from tactical knives to riot gear.

🧠 Closing Insight

The medieval era didn’t just build armies—it forged the modern martial mindset. From feints and formations to ethics and adaptability, the legacy lives in every fighter who trains with intent. It was here that combat became both art and science—a fusion of mind, body, and purpose.

Whether facing a duel, a raid, or a riot, the warrior who thinks tactically, adapts swiftly, and trains with honour carries forward the true inheritance of medieval combat.

🧭 Summary

The Medieval Era was anything but a dark age. From Europe’s armoured knights to the Mamluk cavalry, from Aztec eagle warriors to Japanese samurai, this was a time of diverse and dynamic martial evolution. Combat techniques were shaped by faith, geography, and necessity—yielding unique systems of swordsmanship, mounted warfare, and tactical strategy. Warrior codes emerged, not just to govern violence, but to sanctify it—through chivalry, Bushidō, and the religious mandates of crusaders and ghazis alike.

It was also a time of transmission—where crusades, trade routes, and conflict carried martial knowledge across continents. Manuals, schools, and elite orders preserved these teachings, setting the stage for the next great transformation. As the Renaissance dawned, the sword would not only be wielded with precision—it would be studied with reason. Combat, once tied to chaos and creed, was about to be refined by intellect, anatomy, and art.

Timeline 🕰️📈

| Date | Development/Technique/Event | Region | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 700 CE | Kuvalaymala: Describes martial arts training for non-Kshatriyas at gurukulas. | India | Highlights the spread of martial training beyond the warrior caste. |

| 782 CE | Heian Period Begins: Introduction of tachi swords, precursors to katana. | Japan | Marks early development of samurai weapon arts. |

| c. 800–900 CE | Agni Purana: Lists 130+ weapons, stances, and techniques for armed combat. | India | One of the earliest detailed martial arts manuals. |

| c. 9th–11th Century CE | Viking Combat: Shield tactics, spears, and axes blending into European warfare. | Scandinavia | Influenced European martial systems, especially in England and Normandy. |

| c. 12th Century CE | Knightly Combat: Armoured combat and swordsmanship schools. | Europe | Formalised martial training for knights. |

| 1156–1185 CE | Bushido Code Emerges: During Taira vs. Minamoto conflicts. | Japan | Established the warrior ethos of the samurai class. |

| c. 1200 CE | Kalaripayattu: Flourished in Kerala with strikes, grappling, and weapons. | India | Cited as one of the oldest martial arts with a holistic approach. |

| c. 1200 CE | Malla Purana: Describes malla-yuddha techniques and training. | India | Expanded grappling and submission techniques. |

| c. 1200–1300 CE | Bas-reliefs in Angkor: Depict armed and unarmed combat. | Cambodia | Suggested an early codification of Southeast Asian martial arts. |

| c. 13th Century CE | Mamluk Training: Focus on mounted archery and swordsmanship. | Islamic World | Exemplified professional military martial training. |

| c. 13th–15th Century CE | West African Empires: Use of cavalry, bows, and wrestling. | Mali, Songhai | Demonstrated diverse martial traditions across Africa. |

| c. 13th–15th Century CE | Aztec and Mayan Warfare: Use of macuahuitl and structured warrior societies. | Mesoamerica | Highlighted the ritualistic and battlefield use of weapons. |

| c. 1400 CE | Okinawan Te: Influenced by Chinese and Japanese arts; precursor to karate. | Okinawa (Japan) | Demonstrates early syncretism of martial arts. |

| 1477 CE | Okinawan Weapons Ban: Led to the underground development of unarmed combat techniques. | Okinawa (Japan) | Encouraged the evolution of karate and kobudo. |

Our next post explores the Renaissance to Early Modern Era (15th–18th Century), tracing the decline of armored knights, the rise of rapier duels, Ottoman military dominance, and the impact of colonial encounters on global combat styles.