Discover how martial arts evolved in the Post-WWII to Late 20th Century era, as returning soldiers, cinematic icons, and no-holds-barred competitions reshaped combat sports and self-defense worldwide.

Table of Contents

Introduction

After World War II, the movement of military personnel, shifting global alliances, and expanding media transformed the martial arts landscape. Western soldiers stationed in Japan and Korea trained in Judo, Karate, and Taekwondo, bringing these arts home and fueling new interest in Eastern combat systems. Meanwhile, Japanese and Korean masters began teaching abroad, introducing their disciplines to a wider, eager audience.

As martial arts spread beyond their traditional roots, ideas of competition, realism, and effectiveness began reshaping training methods. By the 1960s and 70s, the search for practical, full-contact fighting intensified, leading to new approaches to striking, grappling, and hybrid combat systems. What began as a post-war fascination would soon explode into a global revolution in combat sports, forever changing the way martial arts were practiced, tested, and understood.

GI / Military-Cross Pollination 🪖🌏🤝🥋

In the wake of World War II, soldiers became unlikely ambassadors of martial arts. From the dojos of Japan to the jungles of Southeast Asia, American and British servicemen encountered new combat systems—and brought them home. This cross-pollination fused Eastern technique with Western pragmatism, sparking a global martial arts explosion that reshaped both military training and civilian fight culture.

Click on the links below to read more.

🇺🇸🪖🌏 American GI’s in Japan, Korea and the Philippines

The Allied occupation of Japan (1945–1952) introduced American soldiers to Judo, Karate, and Kendo—particularly in Okinawa, a Karate stronghold. Many trained in local dojos, learning kata, sparring, and self-defence techniques, and brought these systems back to the US. In Korea, servicemen encountered Taekwondo and Hapkido, expanding their understanding of striking, joint locks, and throws.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, GIs trained with guerrilla fighters skilled in Filipino Martial Arts (FMA)—Kali, Arnis, and Eskrima. These blade and stick systems had been used in resistance against Japanese forces and offered battlefield-tested training in disarms, transitions, and close-quarters tactics. By the 1960s, these martial influences had entered US military combatives, law enforcement programs, and self-defence systems. Base exhibitions and joint training with British forces accelerated this East-West fusion within Western doctrine.

🇬🇧🥊🥋 The British Empire and Martial Adaptation

During the Second World War, British commandos were exposed to Judo through military cross-training with Allied forces, particularly in preparation for close-quarters engagements. The art’s emphasis on throws, chokes, and leverage-based control made it highly adaptable for battlefield use and influenced early British combatives alongside Catch Wrestling and boxing.

In the post-war years, British servicemen stationed in Japan and Korea deepened their martial training, helping to establish Karate and Judo clubs upon returning home. Figures like Vernon Bell, who studied under Henri Plée in France, were instrumental in introducing Shotokan Karate to Britain, while ex-military Judoka helped expand the British Judo Association (BJA). Britain’s long standing boxing culture also shaped this evolution, sparking early Karate vs. Boxing exhibitions in London gyms to test Eastern striking against Western footwork and timing.

By the 1960s, Judo’s efficiency and control-based approach made it a staple in police and military training programmes, while televised martial arts demonstrations further embedded Eastern systems into the British martial landscape.

🥊🎖️🛡️ Continued Exposure Across Southeast Asia

Beyond Japan, Korea, and the Philippines, ongoing deployments in Southeast Asia further expanded martial exchange. While not formally part of military training, American and Commonwealth troops attended local fights and trained at Muay Thai gyms during downtime—attracted by the sport’s intensity and practical striking systems.

Informal exposure to Southeast Asian arts like Muay Thai, Silat, and tribal knife systems deepened the combat literacy of returning veterans. Though not codified into doctrine at the time, these experiences broadened tactical repertoires, many of whom would later influence martial arts communities, police combatives, and civilian training back home.

🌴🥋🗓️📅 Boxing’s Enduring Military Influence

Despite the rise of Asian martial arts, Western boxing remained a pillar of military conditioning—valued for its resilience, simplicity, and combat realism. Its emphasis on footwork, evasive movement, and direct punching gave soldiers essential tools for both sport and survival. Robust boxing programs were maintained in American and British barracks, forging fighters with tough chins, sharp reflexes, and fast hands.

Globally, boxing’s influence also reshaped how martial arts were taught and practiced. Eastern styles like Karate and Taekwondo began integrating head movement, defensive slipping, and combination punching. Muay Thai fighters, too, incorporated boxing’s crisp hand techniques, improving offensive flow and technical depth.

In the West, boxing’s mechanics helped adapt imported martial arts into more familiar and functional systems. Instructors merged efficient striking and footwork with kata, locks, and throws—creating hybridised programs for soldiers, police, and civilians alike.

🌍🥋🚀 Global Phenomenon

For the first time, Eastern martial arts reached a wide Western audience—thanks not to diplomats or film stars, but returning soldiers. These GIs didn’t just bring home techniques—they brought stories, cultural intrigue, and proof of effectiveness. Dojos soon opened across the US, Britain, and beyond, introducing Karate, Judo, Taekwondo, and FMA to eager students.

What began as informal cross-training in far-off bases soon evolved into a global movement. Eastern arts stepped onto the world stage, fusing with Western principles and reshaping the combat landscape for generations to come.

In the wake of World War II, soldiers became unlikely ambassadors of martial arts. From the dojos of Japan to the jungles of Southeast Asia, American and British servicemen encountered new combat systems—and brought them home. This cross-pollination fused Eastern technique with Western pragmatism, sparking a global martial arts explosion that reshaped both military training and civilian fight culture.

Japanese Masters Abroad & Kyokushin Revolution 🥋🌎🌍🌏🔥

In the post-war martial boom, Japanese masters spread Karate across the globe—but one man transformed it entirely. While Funakoshi and Nishiyama brought discipline and tradition to the West, Mas Oyama’s Kyokushin revolution shattered old rules, demanding bare-knuckle realism and full-contact proof. This clash of tradition and toughness would pave the way for hybrid combat sports and redefine striking for the modern era.

Click on the links below to read more.

🥋✈️🏯 Spreading the Art: Japanese Masters Lead Global Expansion

Following the momentum of the Karate boom, Japanese masters took their mission worldwide. Pioneers like Gichin Funakoshi, the father of Shotokan Karate, had already laid the groundwork by bringing Okinawan Karate to mainland Japan, emphasising discipline, simplicity, and striking fundamentals. His students and their successors carried this flame abroad, teaching military personnel, expatriates, and civilian students hungry for authentic martial knowledge.

Hidetaka Nishiyama became a pivotal figure in this international push. Nishiyama not only helped formalise Karate within Japan but also spearheaded its structured spread across North America and Europe. His work with organisations like the Japan Karate Association (JKA) established consistent grading standards and competition formats, ensuring that Karate, no matter where it was practised, maintained a high level of technical quality.

Through cultural exchanges, military base programmes, and early international tournaments, these masters embedded Karate into the global martial arts fabric, giving it legitimacy far beyond its island origins.

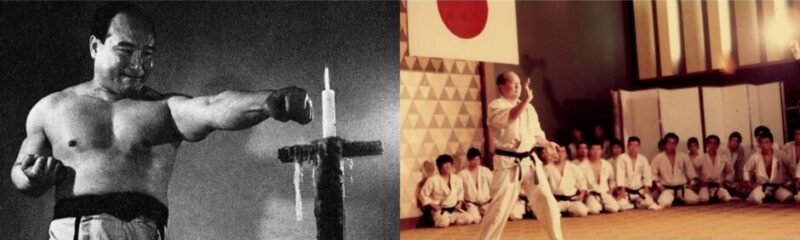

🥋👊🐂 Mas Oyama’s Full-Contact Revolution

While traditional Karate spread globally, one man sought to push it further—into the brutal realm of full-contact, knockdown combat. Mas Oyama, a tough-as-nails Korean-Japanese fighter, founded Kyokushin Karate in the 1960s with an uncompromising vision of realism and physical toughness.

Oyama rejected soft sparring and kata-only practice. Instead, he demanded bone-breaking conditioning, full-contact sparring without gloves, and bare-knuckle power strikes. His notorious demonstrations—fighting bulls, smashing bricks, and dominating challenge fights—shattered public perceptions of Karate as merely a ritualised art.

Kyokushin’s “train hard, fight harder” philosophy quickly attracted fighters worldwide. Its no-nonsense approach appealed to martial artists and military personnel alike, offering a bridge between traditional kata-based systems and live, pressure-tested combat. Kyokushin tournaments, focused on knockouts and physical endurance, laid critical groundwork for the future of combat sports, including the birth of modern kickboxing.

🥋🤜🌍 Building the Bridge to Hybrid Striking Sports

Kyokushin’s relentless pursuit of realism didn’t exist in a vacuum—it helped catalyse the rise of hybrid striking sports. Fighters from Kyokushin backgrounds began testing themselves against Muay Thai boxers and Western kickboxers, sparking early exchanges that would evolve into international kickboxing tournaments.

Kyokushin veterans helped shape organisations like K-1, where Karate’s direct strikes and Muay Thai’s clinch and elbow work collided in thrilling full-contact bouts. The emphasis on heavy conditioning, powerful low kicks, and relentless forward pressure translated seamlessly into this new combat arena.

Beyond tournaments, Kyokushin’s influence permeated law enforcement and military training. Its focus on aggression, mental toughness, and durable striking tactics found a home in hand-to-hand programmes for soldiers and police officers worldwide.

🏯➡️🥋⚔️ From Tradition to Combat Evolution

Through the efforts of masters like Funakoshi and Nishiyama, traditional Karate spread to all corners of the globe. Yet it was Mas Oyama’s Kyokushin revolution that ripped away the final barriers between traditional martial arts and full-contact fighting. Kyokushin forged a crucial bridge—one that would carry martial arts from stylised dojo practice into the rough, unyielding world of hybrid combat sports and modern battlefield training.

Mas Oyama’s Kyokushin Karate emphasised full-contact fighting, toughness, and real-world effectiveness, helping to popularise hard-contact karate worldwide.

These shifts in Karate would not only shape military and law enforcement training—they would lay a cornerstone for modern MMA’s striking systems, as explored in the next post.

The Karate Boom & Dojo Explosion 🥋🌎🔥

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Karate erupted from Okinawan roots to become a global martial arts phenomenon. Fuelled by returning GIs, visionary Japanese instructors, and a public craving structure and strength, Karate moved into schools, church halls, and suburban gyms worldwide. As belt systems drove commercial growth and combat realism sparked internal rifts, Karate’s rise became both a cultural movement and a battlefield of tradition versus adaptation.

Click on the links below to read more.

🏯🥋🏫 From Dojo to High Street: Karate Goes Global

The 1950s to 1970s saw Karate explode into global consciousness, moving from disciplined dojos in Okinawa and mainland Japan to gyms, church halls, and strip-mall studios across the Western world. In the wake of World War II, returning servicemen and pioneering Japanese instructors spread Shotokan, Goju-Ryu, and Wado-Ryu across America, Europe, and beyond. These styles offered structure, discipline, and physical challenge to a population hungry for purpose and personal growth. For many, Karate provided a clean break from the horrors of war, channeling aggression into ritualised strikes and precise kata.

Karate’s accessibility accelerated its rise. Unlike grappling arts, which required mats and close-quarters tuition, Karate’s striking focus allowed classes to take place in community centres and school gyms with minimal equipment. This adaptability saw a proliferation of clubs in cities and suburbs worldwide, offering ordinary people a taste of martial discipline without military enlistment.

🥋🎯💰 The Power of Progress: Belt Systems & Commercialisation

Belt systems and grading structures made progress visible, tangible, and addictive. Belt systems and grading structures made progress visible, tangible, and addictive. Adopted from Judo, the coloured belt hierarchy became both a motivational tool and a commercial asset. Students could see their progress, instructors could build loyalty, and schools could retain members through clearly defined ranks. However, this system also opened the door to shortcuts—the rise of “McDojos” offering fast-track black belts for a fee, diluting quality in favour of quantity.

This commercialisation, while controversial, undeniably contributed to Karate’s global spread. For every serious dojo, there were dozens of casual clubs drawing new audiences into the martial world, laying the groundwork for the martial arts explosion of the late 20th century.

🥋🥊👊 Testing Karate: Boxing Exhibitions & Combat Realism

Karate’s reputation as a practical combat system faced public scrutiny. Karateka sought to prove their art’s effectiveness by testing it against boxers in exhibition matches. These encounters were a reality check: boxing’s head movement, punching combinations, and footwork often exposed Karate’s vulnerabilities in live exchanges. While some traditionalists doubled down on kata and forms, pragmatists began adapting, integrating boxing principles into their striking and sparring.

This cross-pollination sharpened Karate’s combative edge, ensuring that its practitioners could survive and thrive in full-contact environments.

🥋⚔️🔍 The Split: Traditionalists vs. Pragmatists

This fracture between tradition and pragmatism created two streams within Karate:

- The traditionalists, who preserved kata, etiquette, and philosophical teachings.

- The realists, who chased full-contact sparring, combative realism, and cross-training.

This tension fuelled Karate’s evolution, forcing it to confront the realities of unarmed combat in an increasingly competitive martial landscape. Kyokushin, under Mas Oyama, embodied this shift—moving toward full-contact knockdown fighting and brutal conditioning, attracting fighters seeking proof over theory.

🌍🥋🎥 Karate Fever: The Global Explosion

By the 1970s, the Karate boom had reached fever pitch. Fuelled by cinema, television, and its newfound accessibility, Karate transformed from a specialist art into a global phenomenon. In every town, from Tokyo to Texas, new dojos sprang up, shaping a generation of martial artists and laying the groundwork for the modern martial arts industry.

The image of the Karateka in white gi and black belt became a worldwide symbol of discipline and personal power, influencing everything from law enforcement combatives to children’s after-school programmes. The Karate explosion of this era forever changed the global landscape of martial arts.

From the 1960s to 1980s, karate schools and tournaments expanded rapidly across the U.S. and Europe, driving the standardisation of training and helping to establish karate as a global competitive sport.

Globalisation & Media Explosion 🌎📺🔥

As martial arts were introduced to the West, a new force accelerated their spread—mass media. The late 20th century saw martial arts leap from quiet dojos into magazines, television screens, VHS collections, and blockbuster films. What began as specialised combat systems became global obsessions, fuelled by a public eager for authenticity, discipline, and cinematic flair. From Black Belt magazine to Bruce Lee’s explosive stardom, media turned martial arts into a cultural juggernaut, sparking a worldwide boom that reshaped modern combat and entertainment.

Click on the links below to read more.

🏠🥋🌍 Martial Arts Enter the Mainstream

As martial arts expanded through returning servicemen and global masters, the media boom of the late 20th century turbocharged their reach. For the first time, magazines, television, and cinema brought once-obscure fighting styles directly into the living rooms of millions worldwide, transforming martial arts from niche practice to global obsession.

What was once learned in dojos, back alleys, or military camps was now accessible to anyone with curiosity and a magazine subscription. The hunger for authenticity, adventure, and self-mastery fuelled this explosion, as people across continents sought to tap into the fighting spirit of distant cultures.

📰📚🕵️ Magazines and Underground Manuals

Print media played a crucial role in the martial arts surge. Publications like Black Belt (founded 1961) and Inside Kung Fu became essential reading for martial artists hungry for knowledge outside their local dojo. Packed with interviews, technical breakdowns, lineage histories, and philosophy from leading masters, these magazines bridged the gap between continents and gave practitioners direct access to global expertise.

Beyond the mainstream, underground publishers like Paladin Press carved out a raw, unfiltered niche. Their gritty manuals on street survival, military combatives, and “dirty” fighting tactics resonated with soldiers, law enforcement, and self-defence enthusiasts alike. Unlike the polished magazines, these books spoke blunt truths about violence, teaching practical tools for the street and battlefield.

However, this explosion of underground material came with a downside. For every legitimate practitioner sharing battlefield-proven techniques, there emerged a shadowy wave of self-proclaimed masters peddling fantasies. Figures like Ashida Kim and the infamous Black Dragon Society became notorious symbols of martial deception, selling mail-order black belts and exaggerated claims of lethal prowess. This rise of “bullshido” — fraudulent martial arts with flashy promises but no substance — exploited the thirst for knowledge among eager readers, blurring the lines between fact and fiction. While the underground press empowered many, it also opened the floodgates for martial myth-makers and backyard ninjas alike.

📼🥋🏠 VHS Revolution: Martial Arts in Every Living Room

The explosion of home video added fuel to the martial arts fire. VHS tapes promised to turn anyone into a street fighter or silent assassin, flooding homes with accessible, if often dubious, instruction. From genuine training series by respected masters to outlandish backyard productions peddling ninja secrets, the home video craze democratised martial knowledge like never before. For martial artists without access to formal schools, these tapes became gateways to practice—sparking a DIY culture of garage dojos and late-night living room sparring that spread like wildfire across the 1980s.

📺🥋🚀 Martial Arts Hits the Small Screen

Television became a powerful vehicle for martial arts culture. The Green Hornet (1966), with Bruce Lee as Kato, electrified audiences with fast, fluid movements never before seen on Western screens. Soon after, Kung Fu (1972), starring David Carradine, blended Eastern philosophy with action drama, sparking widespread curiosity about Shaolin monks and their mystical fighting arts.

These portrayals didn’t just entertain—they ignited a full-blown martial arts craze. Across the West, Karate dojos and martial arts schools surged in popularity, as viewers sought to step off the couch and into the dojo, turning cinematic inspiration into personal practice.

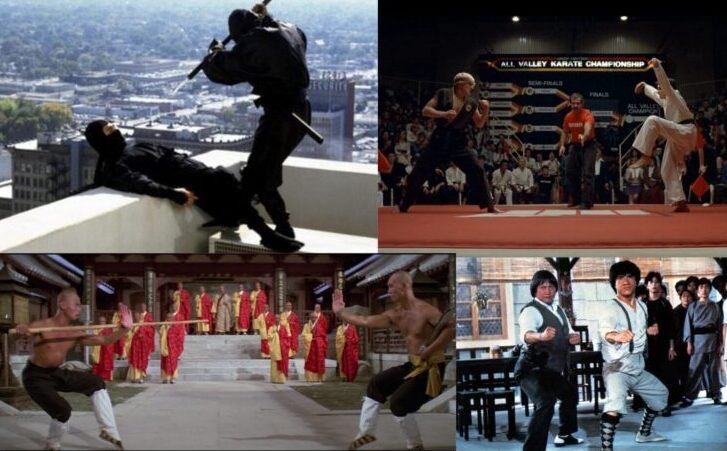

🎥🥋💥 Hong Kong & Japanese Cinema: Grindhouse Glory

Before the 1960s, Western action films relied heavily on gunfights, fist brawls, and swordplay. But in the 1970s, the explosion of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, led by Bruce Lee and the Shaw Brothers, changed everything. Films like The 36th Chamber of Shaolin and The One-Armed Swordsman electrified grindhouse cinemas across America, flooding screens with fast, intricate fight choreography and philosophical undertones. These gritty double features captured the imagination of Western audiences and future filmmakers alike, inspiring icons such as Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez.

Meanwhile, Japan delivered its own hard-hitting contribution through Sonny Chiba, whose brutal Street Fighter series injected graphic violence and raw physicality into the martial arts boom. His Japan Action Club pushed the limits of stunt work and on-screen combat, ensuring Japanese martial arts films stood shoulder to shoulder with their Hong Kong counterparts in the grindhouse circuit.

This cinematic wave didn’t just reshape action choreography—it ignited a global fascination with martial arts, triggering a boom in dojo openings, a flood of martial arts students, and a lasting shift in Western fight culture.

🎬🐉🔥 Kung Fu Craze in Hollywood

Bruce Lee’s magnetic presence redefined martial arts cinema, setting the screen ablaze in both East and West. Films like The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, and Enter the Dragon captivated global audiences, blending high-speed choreography with authentic Kung Fu traditions. Lee’s electrifying fights and undeniable charisma shattered cultural barriers, proving martial arts cinema could resonate worldwide. His impact sparked a worldwide surge in martial arts school enrolments, as fans flooded dojos eager to replicate the skills they saw on screen.

Lee’s legacy paved the way for a new wave of Hong Kong action stars. Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung redefined the genre with their unique blend of physical comedy, jaw-dropping stunts, and relentless choreography. They pushed the boundaries of what was possible in fight scenes, adding humour and daring athleticism to the genre, which only broadened its mass appeal.

🥊🎬🏆 Cultural Lightning Rods: Rocky and The Karate Kid

The late 1970s and 1980s produced two cinematic giants that electrified the fighting spirit of a generation. Rocky and The Karate Kid were not just box office hits—they were cultural detonations, sparking worldwide explosions of interest in martial arts and combat sports.

The Karate Kid and the Dojo Boom

The Karate Kid (1984) blended Karate’s discipline with an underdog story that captured hearts across the globe. Audiences saw themselves in Daniel LaRusso’s journey, and millions were inspired to step into the dojo, eager to find their own “Mr. Miyagi.”

Dojo memberships soared, local tournaments sprang up, and Karate cemented its place as the gateway martial art for a new generation of practitioners. Point-fighting and kata competitions became weekend rituals, giving young fighters their first taste of structured combat and fuelling the hunger for future full-contact formats.

The Rocky Effect: Boxing’s Cinematic Revival

Just as The Karate Kid ignited a passion for Karate, Rocky reignited the global love affair with boxing. Sylvester Stallone’s portrayal of the underdog fighter from Philadelphia captured the raw grit of the boxing gym—sweat-soaked floors, battered gloves, and the relentless pursuit of victory.

Across America and beyond, young fighters laced up their gloves, pounding heavy bags with the same dogged determination they saw on screen. Rocky didn’t just tell a story; he gave every viewer a reason to fight for something.

🥷🎥🌪️ Enter the Ninja

By the 1980s, Hollywood fully embraced the Ninja craze, propelled by Sho Kosugi’s cult classics like Enter the Ninja (1981) and Revenge of the Ninja (1983). These films catapulted Ninjutsu into the public eye, blending stealth tactics, weapons mastery, and shadowy mystique to create a new martial arts sensation. The image of the ninja as an unstoppable, silent assassin captured imaginations worldwide, sparking a global surge in Ninjutsu training.

Figures like Stephen K. Hayes played a pivotal role in bringing authentic Togakure-ryu Ninjutsu to the United States, teaching not only unarmed combat but also bladed weaponry, stealth movement, and camouflage tactics. This growing interest fuelled a commercial explosion: ninja books, mail-order weapons, training videos, and even children’s media like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles flooded the market, embedding the ninja mythos into pop culture.

Yet, as martial arts tastes shifted in the 1990s toward harder-hitting systems like Muay Thai, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, and MMA, the ninja phenomenon began to fade. Still, the legacy of the craze endured. Elements of Ninjutsu persisted in self-defence circles, military training, and entertainment, ensuring the shadow of the ninja never fully disappeared from martial arts history.

🎥🥋💪 80’s-90’s The Age of the Action Hero

Following in their footsteps, Jet Li introduced a new generation to martial arts cinema, blending acrobatic spectacle with traditional Wushu techniques. His lightning-fast choreography and cinematic flair set new standards, influencing Hollywood stunt teams and action directors seeking fresh, dynamic energy in their fight scenes.

Inspired by these Eastern legends, Western action stars like Chuck Norris and Jean-Claude Van Damme bridged the cultural gap, bringing Karate, Taekwondo, and kickboxing to mainstream Hollywood. Their blockbuster successes helped turn martial arts into a global phenomenon, embedding it into the DNA of Western action films and sealing its place as a staple of international cinema.

Martial arts films from the 1970s and 1980s, such as The 36th Chamber of Shaolin and The Karate Kid, played a major role in popularising martial arts worldwide. These films romanticised training, discipline, and personal growth, inspiring millions to take up martial arts and fueling the global boom in dojos, schools, and tournaments.

As martial arts fever swept the globe, practitioners began craving more than ritual and form—they wanted to test themselves in raw, unscripted combat, setting the stage for the brutal rise of full-contact fighting that lay just over the horizon.

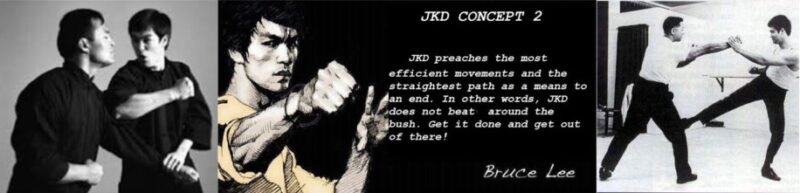

Bruce Lee & Jeet Kune Do (JKD) 🐉🥋🔥

By the 1960s, martial arts in the West were stagnating—trapped in rigid forms and cultural barriers. Bruce Lee shattered that mould. Rooted in Wing Chun but fuelled by street fights and deep philosophy, he launched a rebellion against tradition. His journey wasn’t just the birth of Jeet Kune Do—it was a revolution against martial stagnation itself.

Bruce Lee - The War Against Tradition 🥋🛑⚡

Click on the links below to read more.

🚪🏮🧱 Martial Arts in the West Before Lee: Gatekeepers and Isolation

Before Bruce Lee exploded onto Western screens and seminar circuits, Chinese martial arts—particularly Kung Fu—remained a closely guarded secret, often confined to small, insular Chinatowns in cities like San Francisco, New York, and London.

The few schools that existed were primarily taught in Cantonese or Mandarin, hidden behind cultural barriers and traditions that discouraged teaching outsiders. Many Chinese masters felt a deep-rooted obligation to preserve their knowledge within their communities, fearing that opening up would dilute the art or hand their skills to potential enemies.

This preservation instinct, while understandable, bred stagnation. Without external challenge, techniques risked becoming ceremonial, rigid, and fossilised. As rival arts like Western boxing, judo, and wrestling evolved through competitive testing, many traditional Chinese systems remained frozen, valuing form over function.

A young Bruce Lee saw this—and rebelled.

🌱👊🏮 Wing Chun and the Seeds of Rebellion

Bruce Lee’s martial journey began in the alleys of Hong Kong, where he trained under the renowned Yip Man, a master of Wing Chun Kung Fu. Wing Chun’s close-quarters philosophy, aggressive centreline attacks, and economical movements shaped Lee’s early understanding of combat. Yet, even as he honed his skills, Lee questioned the gaps he saw in the art—its lack of focus on footwork, its limited ground game, and its often theoretical application.

His street fights in Hong Kong’s rough neighbourhoods further shaped his thinking. Lee quickly realised that real-world violence didn’t respect tradition. Adaptation was survival. Fluidity, unpredictability, and ruthless efficiency mattered more than lineage or formality.

These experiences planted the seed for what would become Jeet Kune Do: the realisation that martial arts needed to evolve to remain effective in the face of modern violence.

🌏🚫🏮 The Culture War: Teaching "Foreigners" and Breaking Barriers

When Lee arrived in America, he encountered not just new opportunities, but deep-rooted cultural resistance.

The Chinese martial arts community in the U.S. largely adhered to the old-world belief that Kung Fu knowledge should remain within Chinese circles. Teaching Westerners was frowned upon, and in some cases, outright forbidden. This policy wasn’t just tradition—it was racial exclusion, born of mistrust and a desire to safeguard cultural identity.

Bruce Lee rejected this limitation outright. He believed martial knowledge was for all who sought it with discipline and respect. His decision to openly teach non-Chinese students was an act of defiance, igniting fierce backlash from conservative masters.

This tension culminated in the now-legendary challenge fight against Wong Jack Man, a San Francisco martial artist sent to confront Lee over his refusal to adhere to tradition.

The bout, fierce and controversial, ended in Lee’s victory—but left him deeply frustrated. Even though he won, he felt the fight lasted too long. It solidified his conviction: Chinese martial arts needed to change.

📜🗑️🧹 Lee’s Frustration: The "Classical Mess"

Bruce Lee famously described traditional martial arts as a “classical mess”—bound by excessive formality and disconnected from the realities of combat.

He saw endless forms (kata), rigid sequences, and outdated weapon sets that bore little relevance to modern street violence. For Lee, these practices were akin to rehearsing stage plays while neglecting the chaos of a real brawl.

“To me, ultimately, martial arts mean honestly expressing yourself.”

— Bruce Lee

His mission became clear: dismantle the ivory towers of tradition and build a functional, living martial art that reflected the realities of human combat.

Lee’s rebellion wasn’t against Kung Fu itself—it was against stagnation. He sought to breathe life back into the arts, stripping away the dead weight of ritual to preserve the heart of combat.

🌊🌎🥋 Opening the Floodgates

Bruce Lee’s open defiance of closed-door policies transformed the landscape of martial arts in the West.

His visibility as an actor and his personal charisma drew unprecedented attention to Chinese martial arts, sparking a boom in dojo openings across America, Europe, and beyond.

Wing Chun, his original discipline, surged in popularity alongside JKD, carried by students inspired by Lee’s story and philosophy.

More importantly, Lee’s stand against insularity emboldened a new generation of martial artists to seek knowledge without cultural or stylistic barriers.

Chinatown schools that once resisted outsiders began welcoming students of all backgrounds.

Masters from Hong Kong and mainland China saw the potential of global reach and began teaching internationally.

Filipino Martial Arts, Muay Thai, and Silat followed suit, opening doors once firmly closed.

In short, Bruce Lee didn’t just break cultural taboos—he blew them wide open, lighting the way for global martial arts exchange.

Bruce Lee fought Wong Jack Man over the right to teach non-Chinese students Gong Fu, a decision that infuriated the San Francisco Chinatown community and triggered Wong’s challenge. While the films Dragon (and later Birth of the Dragon) have dramatised the showdown as an epic struggle, in reality, Lee won decisively—finishing the fight within minutes—though it was far grittier and less cinematic than Hollywood portrayed. The victory reinforced Lee’s belief in the need to evolve beyond tradition and sparked his deeper pursuit of Jeet Kune Do.

Jeet Kune Do (JKD) ⚡👊🛤️

Click on the links below to read more.

⛓️✂️ Breaking the Chains of Tradition

As the martial arts world hurtled towards globalisation, Bruce Lee stood as a revolutionary force, shattering the rigid boundaries of style and tradition. Disillusioned with the limitations of classical systems, Lee forged Jeet Kune Do (JKD)—a radical philosophy that rejected dogma in favour of pure efficiency and brutal effectiveness. Drawing from Wing Chun, Western boxing, fencing, wrestling, and street-fighting experience, Lee’s vision was simple yet profound: “Absorb what is useful, discard what is useless, and add what is specifically your own.”

At its heart, JKD prioritised directness, adaptability, and simplicity. Lee championed the principle of interception—hitting first, before the opponent could react. He emphasised fluid movement, non-telegraphed attacks, and dynamic footwork to dominate both distance and timing. The goal was to end confrontations swiftly and decisively, stripping away elaborate rituals in favour of functional combat reality.

In this way, JKD became one of the first modern systems to embrace the philosophy of total fighting readiness—striking, grappling, countering, adapting—all in one seamless flow.

🏫➡️🛣️ Beyond the Dojo, Into the Streets

Unlike many martial arts of his day, Lee’s JKD wasn’t designed for sporting contests or ceremonial displays—it was engineered for the chaotic, unpredictable violence of real-world combat. His approach resonated with street fighters, law enforcement, and military personnel alike, providing a no-frills system that emphasised survival over spectacle.

Lee understood that in a street fight, there were no referees, no points to be scored—only victory or defeat.

This mentality made JKD a quiet pioneer of the emerging global self-defence movement. As violence in urban environments grew during the turbulent 1960s and 70s, countless practitioners saw in Lee’s teachings a way to protect themselves effectively. JKD empowered everyday people to cut through the noise of tradition and focus on what truly mattered in life-or-death situations: speed, aggression, and control of the fight’s rhythm.

🧠🌀☯️ The Mindset Revolution: "No Way as Way"

More than physical technique, JKD was a mental revolution. Lee’s famous creed—“No way as way, no limitation as limitation”—transformed the way fighters thought about combat. JKD wasn’t another style to be codified and memorised—it was the rejection of style itself, a rebellion against fixed patterns in favour of personal truth in combat. Rather than memorise countless pre-set responses, Lee taught his students to develop instinct, flow, and psychological dominance over their opponents.

JKD emphasised deception and rhythm disruption:

- Fakes and feints to draw opponents into traps.

- Broken rhythms to mask intentions.

- Aggressive counter-attacks to seize control of the fight’s pace.

These concepts echo through modern fight psychology and special forces training alike, where breaking an enemy’s will is as important as breaking their body. Lee taught that the fight could be won before the first punch, through mindset, poise, and controlled aggression.

In doing so, he elevated JKD beyond mere physical combat into a complete martial philosophy.

🥋🤼♂️🌱 Cross-Training Culture: Planting the Seeds of Modern MMA

Long before the term “mixed martial arts” entered the global lexicon, JKD laid the cultural foundation for fighters to cross-train beyond their styles.

Lee broke down tribal barriers between striking arts and grappling disciplines, encouraging students to blend the best of boxing, judo, wrestling, and weapon work into their personal arsenal.

This approach ignited a global shift in thinking:

“A Karateka could learn from a wrestler. A boxer could learn from a fencer. Styles were not prisons—they were toolboxes.”

This mindset transformed martial arts culture in the West, inspiring a generation of fighters to seek knowledge beyond their original disciplines. JKD popularised the idea that a true martial artist must be a student of all ranges: striking, clinch, and ground.

This ethos paved the intellectual road to the birth of MMA decades later.

✈️🥋🌍 Global Reach: The Seminar Explosion

While Lee’s premature death in 1973 cut short his personal journey, his vision spread worldwide through seminars led by his senior students—most notably Dan Inosanto. Inosanto expanded JKD beyond its roots, weaving in the fast and ferocious weapons of Filipino Martial Arts (FMA), the precision of Muay Thai, and the emerging grappling dominance of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

These seminars created a new form of global martial arts education.

Before the age of YouTube or online academies, Lee’s disciples travelled from country to country, planting seeds of knowledge in dojos, military academies, and private security circles.

“JKD became not just a system but a bridge, connecting martial artists across continents in a shared quest for efficiency and realism.”

Through these worldwide gatherings, JKD helped dissolve the insularity of traditional arts, uniting a fractured martial landscape into a worldwide exchange of ideas.

👮♂️🔫🥋 Influence on Law Enforcement and Military Combatives

As JKD’s reputation for ruthless practicality spread, it found fertile ground within military and law enforcement circles. Lee’s focus on pre-emptive strikes, ruthless efficiency, and natural movement dovetailed perfectly with the needs of soldiers and officers facing unpredictable violence. Dan Inosanto and other senior instructors brought JKD principles into tactical training, emphasising interception tactics, weapon integration, and rapid disabling strikes for high-risk environments. This integration into early SWAT programmes and military combatives cemented JKD’s status as a battlefield art, not confined to dojos or tournament mats. Modern military systems—combatives courses, security programmes, and police defensive tactics—all owe a quiet debt to the JKD blueprint. Its influence stretches further still, quietly shaping cross-discipline methods in law enforcement defensive tactics, personal protection courses, and modern self-defence systems that blend striking, grappling, and weapon retention into one cohesive survival framework.

🚪🌌⚔️ Legacy: JKD as a Gateway to the Future

Today, Jeet Kune Do stands less as a fixed system and more as a living, breathing philosophy of combat evolution. Its fingerprints are everywhere:

- In MMA’s hybrid skillsets.

- In military combatives focused on pre-emptive violence and control.

- In street-level self-defence courses teaching aggression and adaptability.

- And in the open-minded training ethos that values results over rituals.

His posthumously published Tao of Jeet Kune Do preserved these lessons, becoming a martial arts bible for generations of seekers chasing fluid, adaptive combat. Bruce Lee’s greatest gift was not a particular technique but a mindset—a relentless drive to refine, question, and evolve. JKD taught the world to seek out what works, discard what doesn’t, and never be bound by tradition alone.

“In combat, as in life, the only way is the way that works.“

As martial arts hurtled toward the close of the 20th century, JKD had already cracked open the door to integrated combat thinking. The stage was set for the next great evolution, as fighters worldwide began to pursue the ultimate synthesis of skill, power, and versatility.

Bruce Lee created Jeet Kune Do to break from rigid martial traditions, focusing on practicality, efficiency, and adaptability. JKD emphasises personal expression, constant evolution, and using only what works in real combat.

With Bruce Lee’s blueprint in hand, the global martial arts community had glimpsed the future—a future where the fusion of striking, grappling, and strategy would shape the battlefield of the modern warrior.

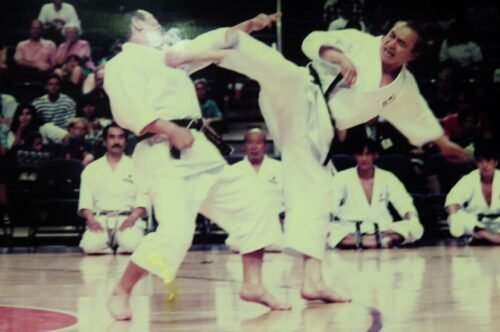

Emergence of Full-Contact Karate & Kickboxing 🥋🥊💥

As the 1970s dawned, striking arts took a sharp turn toward realism. Disillusioned by rigid point sparring, fighters in the US and Japan pushed for full-contact formats—melding Karate with boxing, Muay Thai, and street-tested aggression. What emerged wasn’t just a rule change, but a revolution. American innovation met Japanese precision and Thai ferocity, forging the foundation of modern kickboxing and lighting the fuse for MMA’s future.

Click on the links below to read more.

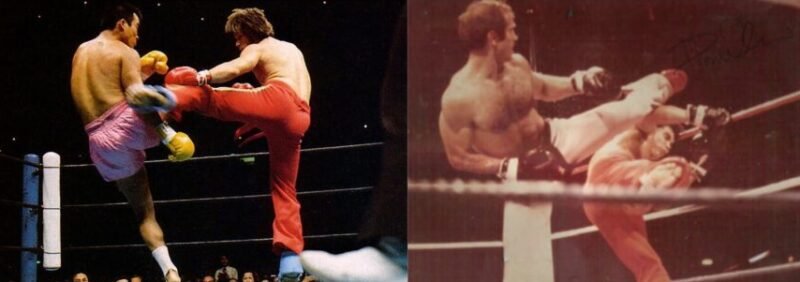

🇯🇵🥋🥊🔥 Japan’s Kickboxing Boom: Karate Meets Muay Thai (1960s)

Even before American kickboxing took off, Japan had already lit the spark by blending Kyokushin Karate with Muay Thai brutality in the 1960s. Fuelled by the punishing ethos of Kyokushin Karate, Japan’s early kickboxers combined iron-body conditioning with brutal striking power, laying the groundwork for hybrid systems. Fighters like Tadashi Sawamura became national icons, showcasing full-contact bouts that combined Karate’s power with Thai-style low kicks and aggressive punching flurries. Japanese promoters sought tougher, more realistic formats, inviting Thai champions to test their mettle against homegrown karateka. These clashes birthed early Japanese kickboxing, which in turn inspired the future K-1 format, fusing East Asian striking philosophies into a thrilling, global-ready spectacle. Japan’s early experiments proved that hybrid striking systems could captivate audiences worldwide, laying crucial groundwork for the full-contact revolution.

🇺🇸🥊🏟️ American Kickboxing (1970s)

Frustrated by Karate’s restrictive point-fighting system, martial artists like Joe Lewis, Bill Wallace, and Benny “The Jet” Urquidez sought a full-contact alternative that allowed continuous striking, harder blows, and knockout finishes. Unlike traditional Karate competitions, which halted action after each clean strike for judges to award points, kickboxing adopted a round-based format, encouraging sustained exchanges and KO-focused strategies. Fighters wore boxing gloves, adopted Western boxing footwork, and engaged in uninterrupted striking, creating a more dynamic and aggressive combat sport.

The Professional Karate Association (PKA) played a pivotal role in legitimising the sport, establishing its first major rule set. Early American Kickboxing, influenced by Karate’s upright stance, initially banned low kicks. However, as the sport evolved, Muay Thai and European kickboxing introduced leg kicks, clinch work, and more fluid striking combinations. By the 1980s, American Kickboxing had gained global recognition, setting the stage for hybrid striking sports. Its emphasis on ring control, footwork, and power punching influenced later systems like Dutch Kickboxing, K-1, and even early MMA striking strategies.

🇹🇭🥊🛡️ Muay Thai Gains International Notice (1970s–1980s)

By the 1970s, Muay Thai had already been Thailand’s national combat sport for centuries, producing generations of hardened fighters. As Western kickboxers traveled to Thailand, they encountered its raw power firsthand in legendary venues like Lumpinee and Rajadamnern Stadiums. Accustomed to upright stances and defensive footwork, many struggled with Muay Thai’s unforgiving leg kicks, clinch control, and relentless forward pressure. Fighters unprepared for the sport’s iron-bodied conditioning often found themselves fatigued before the final rounds, overwhelmed by the sheer intensity of Nak Muay.

As Muay Thai’s reputation spread, K-1 and other full-contact circuits began incorporating leg kicks, knee strikes, and Thai-style conditioning, although early K-1 rules limited clinching. Even under clinch-restricted rules, Thai warriors forced K-1 promoters to acknowledge the devastating power of their style, driving global acceptance of low kicks and knee strikes. Despite this, Thai fighters and those trained in Muay Thai’s punishing style thrived, reshaping global kickboxing strategies. Fighters like Ramon Dekkers proved its effectiveness, inspiring martial artists across disciplines. Inspired by Japanese kickboxing and Muay Thai ferocity, Dutch pioneers like Jan Plas forged a style defined by relentless combinations, thudding leg kicks, and tireless aggression. From Vale Tudo to early MMA, Muay Thai’s raw efficiency made it a fundamental striking system for elite fighters. Today, its emphasis on clinch control, leg destruction, and unrelenting aggression remains a cornerstone of modern MMA, shaping champions across multiple combat sports.

American kickboxing rose in the 1970s, fusing karate and boxing into a full-contact sport. Early pioneers like Benny “The Jet” Urquidez and Bill “Superfoot” Wallace dominated the scene, bringing speed, power, and legitimacy to a new, hard-hitting style of competition.

By the close of the 1980s, the collision of American innovation, Japanese adaptation, and Thai tradition had forged a new global era of striking combat—one that would soon converge with grappling arts in the pursuit of total fighting mastery.

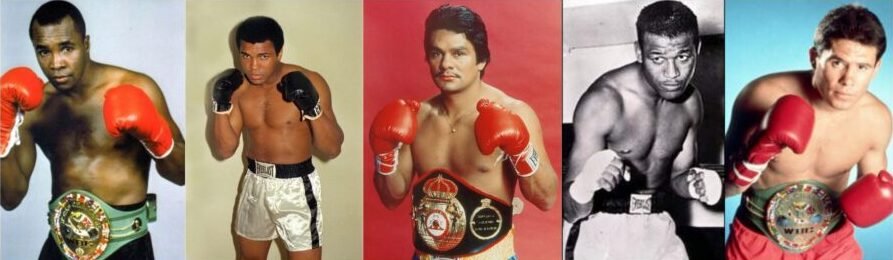

Boxing: The King of Combat Sports 🥊👑🏟️

In the wake of global conflict, boxing emerged from the smoke of WWII as the undisputed titan of combat sports. Grit met glamour as working-class gyms fuelled international icons, and the prize ring became both proving ground and spectacle. From street corners to stadiums, boxing reigned supreme—defining toughness, commanding headlines, and setting the technical standard for striking across the world. This section explores the rise of boxing’s golden era—when the sweet science ruled not only the ring, but the very soul of global combat.

Click on the links below to read more.

🎖️🥊📻 Boxing’s Golden Era

After WWII, boxing stood unrivalled as the world’s premier combat sport. With mass audiences hungry for spectacle, stadiums filled to the rafters and living rooms buzzed with radio broadcasts and early television coverage. Fighters like Rocky Marciano, Joe Louis, and Sugar Ray Robinson became legends, embodying both the grit of post-war survival and the glamour of rising stardom. For millions, boxing wasn’t just entertainment—it was the definitive test of toughness, strategy, and heart.

💵🥊🎥 Big Money, Big Spectacle: Rise of the Prizefighter

Boxing became the first combat sport to generate enormous financial purses, elevating fighters to global celebrity status. Closed-circuit TV and early pay-per-view events turned matchups like Ali vs. Frazier and The Rumble in the Jungle into worldwide phenomena. Promoters mastered the art of hype, and fighters like Muhammad Ali transcended sport, becoming cultural icons. The prize ring offered not only riches, but also a platform for political statements, personal narratives, and international attention that no other martial art could rival at the time.

🌎🥊🎯 Evolution of Styles & Regional Schools

Far from a monolithic sport, boxing developed distinct styles across the world.

Mexican fighters built a reputation for relentless body attacks and granite chins.

Detroit’s Kronk Gym under Emanuel Steward bred aggressive power punchers with high-output offence.

Philadelphia’s gyms perfected defensive brilliance with the famous Philly Shell guard.

Cuba’s amateur system emphasised supreme footwork, evasiveness, and technical precision.

Coaches like Cus D’Amato and Eddie Futch pushed tactical evolution, introducing detailed fight analysis, psychological conditioning, and technical drilling that professionalised preparation at every level. This constant refinement made boxing not just a fight, but a science.

🌍🥊🛡️ Boxing’s Influence on Global Combat Systems

Boxing’s striking precision, footwork, and defensive craft rapidly infiltrated other fighting systems.

Karate and Taekwondo fighters adopted boxing’s head movement and counter-punching mechanics to sharpen their full-contact applications.

Muay Thai athletes blended Western punching combos into their traditional striking, enhancing fluidity and knockout potential.

In military and law enforcement settings, boxing fundamentals were prized for their reliability in high-stress encounters. Fast jabs, explosive straights, and evasive footwork became core components of practical combatives, proving that boxing’s lessons transcended the ring.

🏚️🥊🌟 Boxing Gyms Worldwide: The Corner Gym Revolution

While Eastern martial arts were only just breaking into the Western mainstream, boxing had already achieved worldwide penetration. From smoky basements in London to urban gyms in New York, from the favelas of Brazil to the streets of Manila, boxing gyms were a fixture of working-class neighbourhoods. Affordable, raw, and accessible, these gyms offered young men and women a pathway to discipline, fitness, and even escape from hardship.

Trainers passed down time-tested methods, creating tight-knit communities that nurtured local talent and global champions alike. For countless fighters across continents, boxing wasn’t an exotic art—it was their art, deeply embedded in daily life. This global availability kept boxing on top as the most accessible and effective striking art of the era.

From the 1940s to the early 1990s, legends like Sugar Ray Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Roberto Durán, Sugar Ray Leonard, and Julio César Chávez Sr. defined boxing’s golden era, cementing it as the king of combat sports worldwide.

As the curtain closed on the 1980s, boxing remained the undisputed king of combat sports. Its influence had quietly shaped martial arts schools, military training, and fight culture worldwide—leaving an indelible mark that would continue to echo through the evolution of modern combat.

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and the Crucible of Vale Tudo 🇧🇷🥋

In the back alleys, garages, and underground rings of Brazil, martial arts were stripped down to their rawest form. No rules. No gloves. Just technique versus will. It was here—beneath the spotlight of Vale Tudo and the heat of the Gracie Challenge—that Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu was forged in blood and pressure. As rival styles clashed and ideologies collided, BJJ emerged not through tradition, but through trial—shaped by chaos, sharpened by survival. This section dives into the era where ground fighting proved its worth one fight at a time.

Click on the links below to read more.

🧪 The Gracie Challenge: BJJ’s Trial by Combat

By the 1970s and 1980s, the Gracie family had one mission: to prove the effectiveness of their ground-based jiu-jitsu system in real combat. Through a series of open challenges—fought in garages, dojos, and modest venues—they invited martial artists from every style to engage in no-rules fights designed to test the limits of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ). Unlike traditional grappling arts, BJJ prioritised leverage, positional control, and submission holds, allowing smaller fighters to dismantle larger, stronger opponents through technique rather than brute force.

These raw, often filmed encounters became known as the Gracie Challenge, and they built the mythos around BJJ as a real-world fighting system. At the same time, tensions with Luta Livre—Brazil’s rival no-Gi submission wrestling art—began to boil over. While BJJ relied on the Gi for grips and transitions, Luta Livre dismissed such traditions, focusing on fast, aggressive submissions and wrestling-inspired control. The result was a bitter rivalry marked by dojo stormings, street fights, and brutal Vale Tudo clashes. The feud forced both systems to refine their methods under pressure, sharpening the effectiveness of their respective approaches.

⚔️ Vale Tudo: Brazil’s No-Holds-Barred Arena

While the Gracie Challenge laid the groundwork, the real proving ground for BJJ was Vale Tudo—Brazil’s underground combat sport meaning “anything goes.” Though it had existed since the 1920s, Vale Tudo was revitalised during the 1970s and 1980s, becoming the ultimate arena for martial arts supremacy. These fights featured minimal rules, no gloves, and open-weight matchups, pitting strikers, grapplers, and hybrid fighters against each other in unforgiving conditions.

In these bouts, strikers aimed for early knockouts, while grapplers sought to close the distance, clinch, and drag opponents to the mat—where BJJ’s positional dominance and submissions usually decided the outcome. Fighters from boxing, karate, wrestling, Luta Livre, and other disciplines stepped into the ring to prove their worth, but BJJ fighters, especially those from the Gracie clan, often emerged victorious. This dominance was especially personified in Rickson Gracie, whose performances in single-night tournaments and challenge fights became legendary. Known for his composure, control, and finishing ability, Rickson was the face of BJJ in Vale Tudo and became one of the sport’s most feared champions.

Despite its popularity in the underground, Vale Tudo remained unsanctioned and unregulated, with fights often ending in severe injuries. There were no weight divisions, time limits, or safety measures—just raw survival. Yet from within this chaos, technical truths emerged. The fights revealed not just which style was superior, but which techniques held up under maximum stress. BJJ’s emphasis on conserving energy, maintaining control, and finishing cleanly proved crucial in battles where fatigue and injury were constant threats.

🥋🤼♂️🔥 BJJ vs Luta Livre: The Rivalry That Shaped Modern Grappling

The rise of Vale Tudo coincided with the deepening of the BJJ–Luta Livre rivalry, which became one of the most influential style wars in martial arts history. Fighters like Eugenio Tadeu (Luta Livre) and Renzo Gracie (BJJ) turned their ideological and technical differences into personal vendettas, resulting in riotous brawls, gym invasions, and Vale Tudo matches that drew national attention. Meanwhile, Marco Ruas, a striker with strong Luta Livre roots, challenged the dominance of pure grappling by blending Muay Thai with no-Gi submission wrestling—a prototype of the well-rounded MMA fighter to come.

These clashes pushed BJJ to evolve. Faced with aggressive leg lock attacks and powerful striking, BJJ practitioners began to adopt no-Gi training, wrestling-based takedown defence, and eventually, striking techniques of their own. Luta Livre’s raw efficiency forced BJJ to adapt beyond its traditional base, expanding its arsenal for the realities of unrestricted combat.

🌘 BJJ’s Ascent in the Shadows

By the early 1990s, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu had become Brazil’s dominant grappling system, forged in a climate of chaos, challenge, and cross-disciplinary warfare. Though Vale Tudo remained mostly hidden from the global stage, its influence on combat evolution was undeniable. It exposed the gaps in traditional martial arts, dismantled the myth of the “one-strike knockout,” and served as a brutal testing ground for BJJ’s philosophy of control, efficiency, and technique over size or strength.

Karate had its global federations. Judo had Olympic status. But BJJ had blood-soaked mats, garage challenge fights, and bare-knuckle Vale Tudo wars. It was not theory. It was survival. And what emerged from this underground crucible was no longer just a regional adaptation of Judo—it was a battle-hardened system, refined through decades of real fights.

The Gracie Challenges began in Brazil in the 1920s and 1930s, with open fights against other styles held in gyms and dojos. Rough footage from these matches captured the raw, no-rules grappling that helped build Gracie Jiu-Jitsu’s early reputation. The Challenges continued into the later decades, helping to prove Gracie Jiu-Jitsu’s effectiveness and build its reputation worldwide.

As the 1990s dawned, the underground era was ending. The Gracie family had proven their art in Brazil’s no-holds-barred arenas—now they were ready to prove it to the world.

Soviet Bloc Systems: Behind the Iron Curtain ☭🤼♂️🥋

Behind the Iron Curtain, martial arts weren’t hobbies—they were tools of the state. In the Soviet Union, combat training was engineered for war, control, and dominance. With borders closed and methods concealed, systems like Sambo and Systema evolved in isolation, sharpened by military necessity and ideological resolve. These weren’t arts for demonstration—they were crafts of destruction, forged in secret by soldiers, spies, and state-sanctioned champions. This section explores how the USSR built a combat legacy in silence—and how its fighters emerged ready for war, not applause.

Click on the links below to read more.

🥋 Combat Sambo Refined: Soviet Grappling Powerhouse

Already established in the interwar years, Sambo flourished under the Soviet Union’s state-sponsored sports machine, becoming both a competitive sport and a brutal military combative system. State investment ensured that Sambo athletes mastered explosive takedowns, crippling joint locks, and relentless positional control. Soviet soldiers, Spetsnaz operatives, and police forces trained in Combat Sambo, which fused vicious striking with devastating grappling techniques. Designed for battlefield practicality, it armed fighters with rapid throws, bone-breaking submissions, and ruthless close-range strikes.

While the world marvelled at Soviet dominance in Olympic freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling, few realised Sambo was the unseen backbone behind their success. Sambo competitors, wearing distinctive jackets, introduced dynamic leg locks and aggressive top pressure to the international stage, subtly influencing global grappling standards. Foreign athletes who trained at Soviet institutes quietly spread Sambo techniques abroad, planting seeds that would later take root worldwide. Even without Olympic status, Sambo’s fearsome reputation grew, reinforcing its identity as a legitimate, world-class combat discipline.

🕵️♂️ Systema’s Evolution: The Shadow Art of the Spetsnaz

In contrast to Sambo’s structured sporting platform, Systema remained an enigmatic combat art, cultivated in secrecy for Soviet special forces and intelligence operatives. Eschewing rigid drills, Systema taught instinctive movement, breath control, and natural biomechanics, allowing operatives to flow with relaxed yet brutal efficiency. Its principles of deception, fluid redirection, and psychological warfare made it highly adaptable to irregular combat and clandestine missions.

Western analysts who glimpsed Systema during the Cold War often misunderstood its relaxed, fluid style, mistaking it for choreography or even dismissing it as ineffective. But within Soviet training circles, Systema was prized for its ability to weaponise the human body in unpredictable and ruthless ways, especially in environments where improvisation was survival.

Though concealed from the public during this period, Systema would later emerge as one of the most distinctive combat systems in the post-Soviet era, taught by veterans such as Mikhail Ryabko and Vladimir Vasiliev. But in the Cold War years, it remained a closely guarded secret—shaped for real battlefields, not sport.

🤫 The Cold War’s Hidden Arsenal: Secrecy and Isolation

During the height of the Cold War, Sambo, Combat Sambo, and Systema remained locked behind the Iron Curtain, reserved for Soviet military and elite athletes. Unlike Japanese Karate or Judo, which spread through international federations and friendly tournaments, Soviet martial arts were developed in a closed ecosystem, insulated from Western influence. This deliberate secrecy delayed their global recognition but ensured they evolved with unrelenting focus on real-world effectiveness.

Western observers, lacking exposure, often underestimated Soviet combat systems—viewing them as either obscure wrestling offshoots or theoretical military drills. But in reality, these arts forged some of the world’s most capable hand-to-hand fighters, who combined technical precision with ruthless intent.

🌍 Legacy and International Influence

Although full Western exposure only followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, the groundwork had been laid during these Cold War decades. Sambo’s influence quietly permeated international grappling circuits, particularly through leg attacks and aggressive pressure tactics that found parallels in catch wrestling and No-Gi submission grappling. Systema’s elusive methodology, while less visible, set the stage for future interest in adaptive, reality-based combat philosophies.

The Cold War years preserved these systems in an incubator of military necessity. When the Soviet Union fell in 1991, the floodgates opened—but their legacy had already been forged:

- Military combatives: Sambo and Systema provided foundations for Soviet armed forces and continue to influence modern military training worldwide.

- Law enforcement: Techniques of restraint, weapon retention, and close-quarters control shaped police defensive tactics.

- Combat sports influence: Sambo’s integration of wrestling and submissions fed the emerging hybrid models of global combat sports, later seen in Vale Tudo and MMA.

During the Cold War, Russian martial arts training focused heavily on practicality for military and KGB operatives. Systems like Sambo and Systema emphasised rapid takedowns, joint breaks, weapon disarms, and psychological control, prioritising survival, efficiency, and adaptability in high-risk environments.

Sambo remained out of sight during the Cold War—but as the Iron Curtain began to crumble, it’s time would come. In the years following the Soviet Union’s collapse, fighters trained in this brutal discipline stepped onto the global stage, and the world finally witnessed the combat system that had been forged in silence.

Wrestling: The Silent Backbone of Post-War Combat 🤼♂️🧱🌍

While other martial arts dazzled with mystique or spectacle, wrestling did what it had always done—win through grit, control, and unrelenting pressure. In the aftermath of World War II, it surged quietly across continents, embedded in schools, military programs, and Olympic dreams. Nations like the USSR, the USA, and Iran transformed it into both a national sport and a combat science. This section explores how wrestling, without fanfare or flair, became the silent backbone of global combat—laying the groundwork for everything from modern MMA to battlefield grappling.

Click on the links below to read more.

📈🤼♂️🎯 Wrestling’s Post-War Surge

While flashier martial arts took to the spotlight, wrestling quietly entrenched itself as a cornerstone of combat sports worldwide. In post-WWII Europe, the Soviet Union pushed wrestling to international dominance, refining techniques with scientific precision and relentless drilling. Meanwhile, the United States saw explosive growth in collegiate and high school wrestling, creating a vast pipeline of skilled grapplers. From Eastern Europe to the Americas, wrestling became one of the most accessible and effective combat systems of the era, thriving both as a competitive sport and a combative base.

🌎🤼♂️🛠️ A Global Blueprint for Grappling

Wrestling’s beauty lay in its simplicity and universal application. With minimal equipment and direct, instinctive techniques, it flourished in gyms, school halls, and military camps alike. The folkstyle and freestyle approaches developed distinct regional flavours:

- American folkstyle emphasised control and pinning.

- Eastern European and Soviet wrestling prioritised throws, upper body dominance, and chain-wrestling flow.

- Iranian wrestling brought a blend of strength and flowing technique, deeply rooted in cultural heritage.

This international cross-pollination not only enriched wrestling but created a global exchange of techniques that would later feed into judo groundwork, Sambo, and the rise of MMA.

🎖️🤼♂️🛡️ Wrestling in Military Training

Wrestling’s raw practicality made it ideal for military combatives. Quick takedowns, positional control, and the ability to neutralise opponents without weapons were invaluable on the battlefield. Across military academies and bootcamps, wrestling fundamentals became standard issue, offering soldiers fast, instinctive grappling skills applicable to chaotic combat scenarios.

🎭🤼♂️📺 Pro Wrestling and Public Imagination

Parallel to competitive wrestling, professional wrestling kept the sport’s imagery alive in mainstream culture. Though choreographed for entertainment, pro wrestling showcased throws, locks, and holds to millions, embedding grappling concepts in the public psyche. In Japan, the shoot-style movement of the late 70s and 80s blurred the lines, as some pro wrestlers transitioned into legitimate fighters, contributing to the development of Japanese MMA and hybrid combat sports.

🧬🤼♂️🏆 Legacy and Long-Term Impact

By the late 20th century, wrestling had quietly built itself into the global backbone of grappling. Whether in Olympic arenas, military academies, or future MMA cages, wrestling’s influence was everywhere. Its relentless focus on control, leverage, and endurance created not just fighters, but an entire grappling culture. The lessons of wrestling—positional dominance, pressure, and persistence—would continue to shape the future of combat sports and real-world fighting systems alike.

In countries like the United States, Iran, and Russia, wrestling became deeply ingrained in national culture, taught through school and university programmes. It has produced generations of elite competitors and preserved wrestling’s relevance as both a competitive sport and a practical combat skill.

The Olympic Stage: Martial Arts Go Global 🏛️🥋🌐

As the 20th century unfolded, the Olympic Games became the world’s grandest stage—not just for nations, but for martial traditions seeking global legitimacy. Once confined to dojos, training halls, and cultural rituals, combat systems like Judo, Taekwondo, and Greco-Roman wrestling were thrust into the international spotlight. This era didn’t just elevate athletes—it transformed martial arts into structured sports, national symbols, and global disciplines. The following section explores how the Olympic stage reshaped the trajectory of martial arts, turning ancient systems into modern spectacles with worldwide reach.

Click on the links below to read more.

🥋🥇🇯🇵 Judo: The Breakthrough Pioneer

In 1964, Judo became the first Asian martial art included in the Olympics, cementing Japan’s influence on global combat sports. Its structured ruleset and emphasis on clean throws and submissions made it accessible to new audiences worldwide. Olympic exposure accelerated Judo’s growth in Europe, the Americas, and beyond, embedding it in military training, police tactics, and civilian sport.

🥊🏛️🕰️ Boxing: The Constant Pillar

Boxing had been a mainstay of the Olympics since 1904 (men’s division), but post-WWII saw its popularity soar. Olympic boxing introduced viewers to rising talents from Cuba, the Soviet Union, and the United States—nations that treated Olympic medals as symbols of national prestige. Legendary amateur programmes, especially in Cuba and Eastern Europe, produced fighters who dominated Olympic podiums and later turned professional, fuelling global boxing’s commercial boom.

🤼♂️🏆🥇 Wrestling: Greco-Roman & Freestyle Dominance

Both Greco-Roman and freestyle wrestling remained core Olympic events, showcasing the pinnacle of grappling skill. Soviet and Eastern Bloc dominance in freestyle, along with American collegiate wrestlers transitioning to international competition, kept wrestling deeply relevant. Olympic success inspired grassroots programmes worldwide, reinforcing wrestling’s importance in sport and military training.

🇰🇷🥋🏅 Taekwondo: Korea’s Global Victory

Taekwondo made its Olympic debut as a demonstration sport in 1988 (Seoul Olympics), capitalising on South Korea’s push to globalise their national art. Its high-flying kicks, fast-paced matches, and clear scoring system made it a crowd favourite. Even before its official inclusion in 2000, Taekwondo’s Olympic visibility accelerated its spread into dojos worldwide, especially in the Americas and Europe.

🥋🐢🎖️ Karate: Late to the Party

Karate’s journey to Olympic recognition was long and political, but even without early inclusion, it thrived on the international circuit during the post-war period. World championships and televised tournaments kept Karate in the public eye, and its Olympic debut in Tokyo 2020, though late, was built on decades of global groundwork laid during this era.

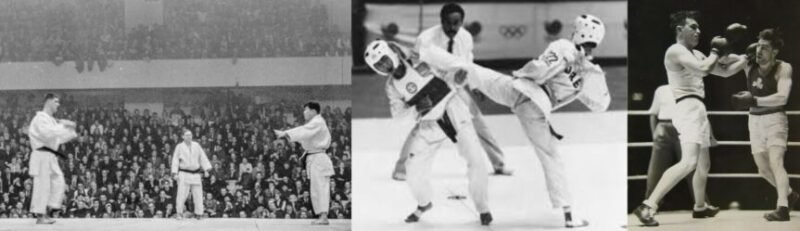

Combat sports have been a core part of the Olympic Games since their modern revival. Wrestling entered the Olympics in 1896, boxing in 1904, and judo in 1964. Taekwondo became official in 2000, and karate debuted briefly at the Tokyo 2020 Games.

The Olympic spotlight validated these martial arts as disciplined, competitive, and globally respected systems. For millions around the world, the Olympics were not just a spectacle—they were an invitation to train, compete, and embrace martial arts as part of the global sporting community.

Military & Police Combatives 🎖️👮♂️🥋

As warfare shifted to urban terrain and police forces faced rising accountability, combatives had to adapt. The late 20th century demanded systems that were efficient, adaptable, and grounded in real-world conditions. Militaries required techniques that worked under extreme pressure, while law enforcement focused on control, de-escalation, and public safety. In this environment, martial arts evolved from traditional disciplines into practical, purpose-driven systems. The following section explores how modern military and police combatives were reshaped by necessity, psychology, and the realities of contemporary conflict.

Click on the links below to read more.

🇮🇱🥋⚡ Krav Maga: From Military Doctrine to Global Self-Defence

Refined in the wake of Israel’s formation, Krav Maga evolved within the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) as a brutally efficient system for modern warfare, urban combat, and counterterrorism. Drawing from street-fighting roots, it integrated real-world tactics—weapon disarms, multiple attacker responses, and stress-condition training—to prioritise speed, aggression, and instinctive defence.

By the late 20th century, students of founder Imi Lichtenfeld, such as Eyal Yanilov and Darren Levine, helped standardise Krav Maga for broader use. Adapted for law enforcement, security, and civilian self-defence, Krav Maga’s curriculum expanded to address legal force, situational awareness, and everyday threats like armed muggings or home invasions. Its emphasis on rapid neutralisation, simplicity under pressure, and scenario-based realism made it a global leader in modern combatives.

👮♂️🤼♂️🔒 Police Forces and the Shift Toward Control-Based Tactics

Parallel to military developments, global police forces re-evaluated their approach to close-quarters engagement. Boxing, Judo, and baton techniques remained staples, but many departments moved toward non-lethal control tactics, especially in the face of rising public scrutiny and civil rights advocacy.

In the United States and Brazil, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) gained traction for its emphasis on positional control and submissions, allowing officers to subdue suspects with minimal force. Training focused on de-escalation, joint locks, and ground control—prioritising restraint over strikes. This tactical shift reflected a broader trend: law enforcement needed methods that balanced officer safety, legal responsibility, and public trust.

🧠🥋🏙️ Toward Reality-Based Combat Systems (RBCS)

By the 1990s, new systems emerged that reflected the evolving needs of both soldiers and law enforcement in urban, unpredictable environments. Programs like the SPEAR System, developed by Tony Blauer, focused on instinctive reactions and stress-response training, laying early groundwork for the Reality-Based Self-Defence (RBSD) movement. These systems combined the lessons of military combatives with behavioural psychology and scenario-specific tactics—marking a shift toward the more holistic, adaptable frameworks explored in the decades to come.

Since the 1980s, police combatives have increasingly incorporated wrestling and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, focusing on takedowns, control, and restraint to manage suspects with minimal force.

Lessons from the Post-WWII Era

What Endures ⚔️ 🤼 👊🏼

The decades following World War II were a crucible of transformation for martial arts. What began as a global cross-pollination of ancient traditions rapidly evolved into a battlefield of ideas, styles, and systems. Martial arts were tested in rings, alleys, garages, and combat zones—forced to evolve or fade. From this pressure emerged a new martial era: focused not on lineage, but on what worked when it mattered most.

📌 Cross-Pollination Through Military and Cultural Exchange

Returning GIs and Commonwealth servicemen became unexpected ambassadors for martial arts, having trained in Judo, Karate, Taekwondo, and Filipino Martial Arts (FMA) during deployments in Japan, Korea, and the Philippines. These systems—once bound by regional traditions—began appearing in Western suburbs and military academies. As dojos opened across the West, hybridisation became inevitable, blending Eastern techniques with Western footwork, conditioning, and mindset.

📌 Media Explosion and the Dojo Boom

The rise of martial arts cinema, magazines, and VHS tapes launched martial arts into global consciousness. Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, and grindhouse action films turned martial arts into mass entertainment, inspiring millions to train. Yet with fame came fantasy: the era also birthed Bullshido, McDojos, and a flood of exaggerated claims and pseudoscience that diluted martial integrity.

📌 Martial Arts as Lifestyle and Identity

For the first time, martial arts became more than a skill—it became an identity. Influenced by Bruce Lee’s philosophy and the rise of dojo culture, practitioners began seeing themselves as warriors, philosophers, and athletes. This identity shift built subcultures around BJJ, Karate, Muay Thai, and JKD, shaping how generations would train, think, and live.

📌 Codification of Technique & Competitive Systems

As martial arts globalised, federations and governing bodies began to formalise their practices. Judo entered the Olympics in 1964, and Karate, Taekwondo, and Wrestling developed international competition standards. While some argued this diluted realism, others saw it as a necessary step toward broader recognition and refinement. The era balanced tradition with testing, setting the groundwork for future professional combat sports.

📌 From Ritual to Realism: The Full-Contact Revolution

By the 1960s, practitioners were no longer satisfied with point-fighting or ceremonial sparring. Styles like Kyokushin Karate, American Kickboxing, Japanese Kickboxing, and Muay Thai emerged as brutally honest systems where knockouts, not points, settled disputes. The rise of full-contact tournaments tested traditional arts under pressure, exposing limitations and sparking the earliest seeds of modern MMA thinking.

📌 Combat Conditioning and Functional Fitness

Fighters needed more than technique—they needed engines. Kyokushin conditioning, Muay Thai pad work, and wrestling circuits introduced a new level of toughness. The shift from traditional kata to martial-specific fitness marked the start of today’s obsession with functional training, durability, and fight readiness.

📌 Rise of Bruce Lee and the Functional Mindset

Bruce Lee’s creation of Jeet Kune Do (JKD) was a declaration of war against dogma. He rejected fixed patterns and championed efficiency, interception, and personal expression. His philosophy accelerated a cultural shift: martial arts should adapt, not repeat; test, not imitate. JKD helped collapse stylistic borders, inspiring a generation to cross-train and prepare for real combat, not rituals.

📌 Birth of Modern Grappling Supremacy

In Brazil, Vale Tudo became a proving ground for effectiveness. The Gracie Challenge and violent clashes with Luta Livre forced Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu to evolve under real duress. Grapplers prioritised leverage, control, and submissions, creating a ground-based system that consistently dismantled striking arts in no-rules fights. BJJ wasn’t designed for points—it was built for survival.

📌 Wrestling’s Silent Influence

Amid cinematic flair and exotic styles, wrestling quietly shaped the foundation of modern combat. The Soviet Union refined it into a powerhouse through Sambo and freestyle dominance. Meanwhile, in the US, folkstyle and collegiate wrestling created an army of disciplined grapplers. Wrestling’s emphasis on control, pressure, and stamina would later become critical to MMA, military training, and law enforcement.

📌 Behind the Iron Curtain

Behind the Iron Curtain, the USSR developed Combat Sambo and Systema—rugged, efficient arts forged in secrecy for special forces and Spetsnaz operatives. Where Sambo focused on brutal grappling and leg locks, Systema taught fluid strikes, deception, and survival under duress. Though hidden from the world, these systems evolved into some of the most unique modern combatives post-Cold War.

📌 Real-World Combat: Military, Police, and Urban Adaptation

As conflict moved into cities and policing demands grew, martial arts evolved for real-world application. Systems like Krav Maga, Combat Sambo, Jeet Kune Do, and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu were embraced by military and police units for their focus on pre-emptive strikes, weapon defence, and control under pressure.

Meanwhile, urban-focused systems like SPEAR and early RBSD programmes tackled threats like confined spaces, multiple attackers, and legal use-of-force limits. These stripped-down, efficient systems prioritised function over tradition, arming professionals and civilians alike for modern violence—where survival depends on speed, awareness, and ruthless simplicity.

🧭 Summary