This post explores the roots of MMA, tracing its origins through the gritty world of no-rules fights, hybrid competitions, and the pioneers who dared to break tradition. See how decades of cross-discipline clashes shaped the evolution of modern combat, leading to the ultimate proving ground—the birth of the UFC.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Before the term “Mixed Martial Arts” existed, a quiet revolution was already reshaping combat. Around the world, fighters began stepping outside the comfort of their styles, engaging in open-rules contests that shattered the myth of a “perfect martial art.” From the brutal rings of Brazil’s Vale Tudo to Soviet military grappling, Japan’s shoot-style promotions, and America’s underground circuits—tradition was being pressure-tested.

These weren’t exhibitions. They were stress tests for systems—and few emerged unchanged.

By the 1970s and ’80s, pioneers like Bruce Lee and Jim Arvanitis had begun blending disciplines in pursuit of effectiveness over ideology. At the same time, new hybrid leagues like Shooto, Pancrase, and RINGS were proving what many fighters had already learned the hard way: no single style was complete.

Then, in 1993, one event brought these global undercurrents crashing into the mainstream. It wasn’t the beginning of something new. It was the collision of everything that came before.

🥋 The Age of Style vs Style (1920s–1970s)

Long before the term “Mixed Martial Arts” existed, fighters across the world were already stepping into the unknown. Whether in carnivals, dojos, or underground gyms, martial artists began challenging the idea that their style alone was enough. These weren’t demonstrations or exhibitions—they were full-contact reality checks that shattered the illusion of martial supremacy.

Time and again, respected arts like karate, judo, boxing, and wrestling were pitted against each other in brutal, often mismatched contests. And each time, the outcome was clear: no one style had all the answers.

Click on the links below to read more.

🌎 Maeda vs The World – Laying the Groundwork for BJJ

The story of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu doesn’t begin in Brazil—it begins with a wandering Judoka in search of real fights. Mitsuyo Maeda, a Kodokan Judo black belt and seasoned prizefighter, travelled through dozens of countries in the early 20th century, taking on wrestlers, boxers, savate fighters, and strongmen in open challenge matches. These weren’t choreographed exhibitions—they were chaotic scraps fought on dirty mats, concrete floors, and makeshift rings.

Unlike most of his peers, Maeda adapted his Judo to survive this chaos. He shifted focus toward ground control, positional dominance, and submissions, distancing himself from Judo’s classical emphasis on throws and clean technique.

When Maeda settled in Brazil, he passed on this philosophy to Carlos Gracie, who—with his brother Hélio—refined it even further. They stripped it down for smaller, weaker fighters, emphasising leverage, timing, and defence from the bottom. The result was Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu—not a sport, but a survival system.

🤼♂️ Judo vs Catch Wrestling – Hybrid Grappling Takes Shape

Meanwhile, in Europe and Japan, another clash of systems was playing out. As Judo spread internationally, it collided with a grittier, more brutal rival: Catch Wrestling. Rooted in carnival “hooking” contests and Lancashire folk wrestling, Catch featured brutal joint locks, neck cranks, and top pressure submissions. Where Judo prized clean throws and pinning control, Catch favoured pain, pressure, and finishes.

Between the 1930s and 1950s, Judokas and Catch Wrestlers met in a series of mixed-rules bouts—especially in Japan, where Western “shooters” became attractions. Among them was Billy Robinson, a product of the Wigan “Snake Pit”—a gym infamous for breaking both bodies and egos.

Out of these clashes emerged Shoot Wrestling, with figures like Karl Gotch combining Catch’s submissions with Judo’s throws and positional flow. This blend became the foundation for Japan’s shoot-style wrestling scene, eventually spawning promotions like UWF, Shooto, and Pancrase—precursors to MMA’s technical depth.

🥊 Boxers vs Grapplers – The Stand-Up Illusion Falls

For decades, striking-based arts like boxing and karate enjoyed a dominant public image. Cinema and cultural myth painted them as unbeatable—one clean punch and the fight was over. But real-world matchups exposed the flaws in this illusion.

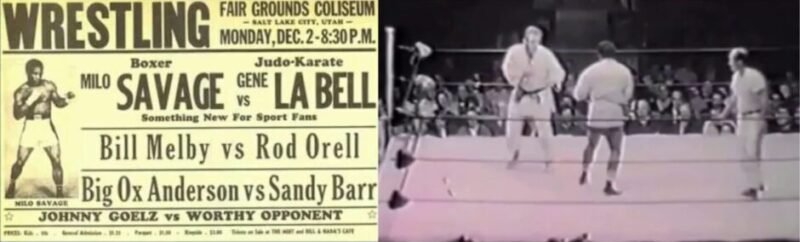

In 1963, Judo master Gene LeBell faced boxer Milo Savage in a mixed-rules bout. Wearing a gi, LeBell absorbed punches, closed the distance, and choked the boxer unconscious. The bout was ugly, controversial—but conclusive. Grappling nullified striking the moment distance was broken.

Then came the infamous Ali vs. Inoki match in 1976. The world’s greatest boxer faced a Japanese pro wrestler in a bout hyped as the ultimate showdown. But Inoki fought from his back, kicking at Ali’s legs for 15 rounds. Ali landed just six punches, while Inoki’s low kicks caused severe damage. It was awkward—but revealing. Boxing had no answer for grounded or hybrid attacks.

📌 Lessons from the First Era of Collision

This period shattered the myth of style purity. What worked in theory—under fixed rules or within the confines of tradition—collapsed under real pressure.

- Karatekas crumbled when taken down.

- Judokas lacked finishing tools on the ground.

- Boxers were vulnerable once clinched.

- Catch Wrestlers struggled against explosive throws and positional reversals.

Each clash revealed blind spots, and each blind spot demanded adaptation.

Early style-vs-style matches, such as judo versus boxing exhibitions, tested the effectiveness of different martial systems under real conditions. Fights like Gene LeBell’s 1963 bout against boxer Milo Savage highlighted the dominance of grappling over pure striking when rules were limited, laying the groundwork for modern mixed martial arts.

🧭 What This Era Gave to MMA

This was the era that punched holes through tradition and lit the fuse for MMA. It proved that real fighting isn’t about style—it’s about adaptability. These early showdowns were more than scraps; they were reality checks for the martial arts world. And they planted the seed of a new idea:

To survive, fighters would have to evolve.

🧠 The Idea Was Already Out There: A World Ready for MMA

Long before the Octagon lit up in 1993, the world was already asking the question:

“Which martial art would win in a real fight?”

By the 1970s and ’80s, the idea of style-vs-style combat had embedded itself in both pop culture and martial discourse. From Bruce Lee’s philosophy of absorbing what is useful to Enter the Dragon’s underground tournament fantasy, audiences were primed for the reality of cross-style combat. Lee’s declaration:

“The best style is no style.”

A concept that would later become the foundation of MMA.

The 80s brought more fuel to the fire. Films like Bloodsport and Kickboxer glamorised the idea of underground tournaments where boxers, karatekas, wrestlers, and ninjas fought for supremacy. Meanwhile, martial arts magazines ran fantasy matchups between Kung Fu and Muay Thai, or Karate versus Wrestling.

Martial arts films like Bloodsport (1988) helped popularise the idea of mixed-style competitions, showcasing fighters from different backgrounds facing off under minimal rules. These portrayals fuelled public imagination and anticipated the real-world rise of mixed martial arts decades later.

📺 Pop culture imagined it. Fighters debated it. But no one had truly tested it.

Behind the scenes, the reality was catching up.

- In Japan, Shooto was quietly developing into a proto-MMA format.

- In Brazil, Vale Tudo raged in underground arenas.

- In Europe, hybrid kickboxing and catch wrestling schools were blending arts out of necessity.

And in American martial arts circles, practitioners were beginning to question tradition. The idea of a “complete fighter” was forming—not just someone skilled in one discipline, but someone who could strike, clinch, grapple, and adapt.

🥋 From Gracie Challenge to Global Domination

By the early 1990s, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu had been forged in the crucible of Vale Tudo and hardened through decades of real fights. In garages, dojos, and backroom brawls, the Gracie family had dismantled strikers, wrestlers, and martial artists of every stripe—proving that leverage, control, and submissions could neutralise brute force. But outside Brazil, few had seen it. The myth had yet to become a movement.

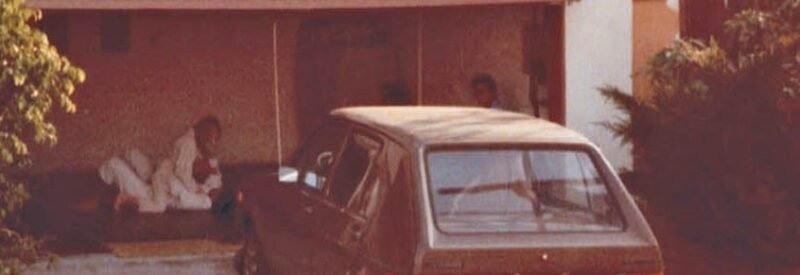

That transformation began in the 1970s, when Rorion Gracie, son of Hélio, moved to California with a plan to quietly ignite a revolution. He started small—teaching Jiu-Jitsu out of his garage, giving demonstrations, and hosting informal challenge matches. Police departments, military units, and martial arts instructors began to take notice. Through patience, charisma, and calculated marketing, Rorion began to plant the seeds of BJJ’s American expansion, long before the world had even heard the term.

But this wasn’t just about spreading knowledge—it was about proving a point. For decades, the Gracie Challenge had been their calling card: open-invite, no-rules fights against any style, any size. Rorion didn’t just want to continue the tradition—he wanted to broadcast it to the world.

To do that, he needed a stage.

Upon his move to the USA, Rorion Gracie brought the Gracie Challenge with him, setting up the original Gracie Garage in California in 1979. From this modest base, he offered free lessons and issued open challenges, helping to build Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu’s early reputation in the United States.

🟥⚒️ The Role of Sambo in MMA’s Global Awakening

The fall of the Iron Curtain didn’t just open borders—it unleashed a storm of hidden martial systems onto the world stage. Chief among them was Sambo, the Soviet Union’s brutal, battle-born art that fused judo, wrestling, and striking into a seamless weapon. Once confined to elite soldiers and national athletes, Sambo’s practitioners exploded onto the MMA scene with a new kind of violence—calculated, suffocating, and surgically effective. This section explores how Sambo, through icons like Fedor and Volk Han, rewired the fight game and reshaped MMA’s global DNA.

Click on the links below to read more.

🔓 From Iron Curtain to Octagon

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, its once-guarded combat systems were suddenly thrust onto the global stage. Among them, Sambo emerged as a devastating hybrid art—blending takedowns, submissions, and strikes into a complete fighting style. Previously limited to Soviet athletes and elite military units, Sambo now fuelled the rise of fighters like Oleg Taktarov, who won UFC 6, and Fedor Emelianenko, who would go on to dominate PRIDE’s heavyweight division.

With explosive throws, aggressive top control, and signature leg attacks, Sambo athletes exposed gaps in other systems and forced MMA to evolve. Early success in RINGS, PRIDE, and the UFC proved this wasn’t just another folk style—it was battlefield-tested combat adapted for the cage.

🥊 Combat Sambo: Striking, Submissions & Survival

What set Combat Sambo apart from arts like Judo or Catch Wrestling was its built-in realism. It wasn’t designed for point scoring or sport—it was engineered for survival. Striking, grappling, submissions, and even weapon disarms were part of the curriculum. In fact, Soviet instructors tested techniques in high-risk scenarios—military drills, covert operations, and prison riot control—where failure meant death or mission compromise.

Early Sambo competitions often resembled Vale Tudo matches: minimal rules, full contact, and rapid finishes. When these athletes entered the MMA scene, their ability to blend throws into submissions or chain takedowns with ground-and-pound gave them a unique edge—tactical, brutal, and adaptive.

🇷🇺 Sambo’s Legacy – Fedor & Volk Han

No fighter embodied Sambo’s full spectrum like Fedor Emelianenko. With knockout power, clinical throws, and seamless transitions into submissions, Fedor became the blueprint for the modern heavyweight: well-rounded, stoic, and lethal.

Meanwhile, Volk Han, a standout in Japan’s RINGS circuit, brought a fluid, creative submission game that dazzled fans and confused opponents. His wrist locks, rolling leg entanglements, and positional awareness made him a cult figure among catch wrestlers and submission grapplers, long before mainstream MMA caught on.

These pioneers didn’t fight from a base—they were the base. And in doing so, they proved that Soviet combat systems had not only survived the Cold War—they were ready to dominate the next one.

Sambo fighters made an early impact in the UFC. Oleg Taktarov demonstrated its effectiveness by winning UFC 6 in 1995, while Fedor Emelianenko later became a global MMA icon, blending Sambo and striking to dominate the heavyweight division.

🧬 Pioneers and Influences (1970s–1990s)

While the style-vs-style wars exposed gaps in tradition, a handful of innovators quietly began building bridges—between arts, countries, and philosophies. These were not just fighters. They were thinkers, coaches, system creators, and cultural disruptors who questioned everything martial arts claimed to be.

Click on the links below to read more.

🧱 Gene LeBell – The First Cross-Training Coach

Gene LeBell was more than a Judo champion—he was martial arts glue. Known for choking out a boxer in 1963, he was also a stuntman, pro wrestler, and cross-discipline advocate who trained Bruce Lee, advised Chuck Norris, and later reffed at UFC 1.

He was one of the first Americans to show that throwing, striking, and submitting could—and should—coexist. While others clung to lineage, LeBell built bridges between arts, and in doing so, helped shape both JKD and early MMA consciousness.

📜 Satoru Sayama – The Blueprint Before the Octagon

Before the UFC ever lit up an arena, Satoru Sayama—the original “Tiger Mask”—had already outlined MMA’s future with startling clarity. In 1985, he introduced a combat sport blueprint that was years ahead of its time.

His vision was called Shooto, and it came with

- Weight classes.

- Timed rounds.

- A scoring system.

- Striking, clinch, takedowns, and ground grappling.

- Unified training across all ranges.

Sayama wasn’t guessing—he was designing MMA before it had a name. Shooto was structured, skill-driven, and pressure-tested under live conditions. It laid the foundation not just for Japan’s fight culture, but for how modern MMA would function globally.

While Sayama built Shooto on structured rules and cross-range training, Matt Thornton would soon echo the same realism-driven ethos in the West—training that worked under resistance, not choreography.

🐉 Bruce Lee & Jeet Kune Do – The Blueprint Before the Sport

In the 1970s, Bruce Lee tore away from martial orthodoxy. Disillusioned by rigid katas and stylistic dogma, he advocated a radical principle:

Take what works. Discard what doesn’t. Adapt it to yourself.

His system, Jeet Kune Do, fused boxing, Wing Chun, fencing, wrestling, and street-fighting ideas—emphasising flow, efficiency, and chaos readiness.

Lee’s famous mantra:

“Styles tend to separate men.”

was a direct rebuke of martial tribalism. He saw real fighting not as ceremony, but as survival.

Though JKD was never a formal sport and Lee never competed in sanctioned bouts, his influence runs deep. Fighters like Georges St-Pierre and Anderson Silva later cited him not for his techniques—but for his mindset:

Freedom. Adaptation. Truth over tradition.

⚔️ Marco Ruas – The Prototype of the Modern Fighter

Before Georges St-Pierre or Jon Jones, there was Marco Ruas—a no-nonsense Brazilian who kicked like a Thai, grappled like a wrestler, and punched like a boxer.

While his breakout came with his UFC 7 victory, Ruas had already been blending systems in the Vale Tudo scene. Ruas famously called his system “Ruas Vale Tudo” and was among the first to mix Muay Thai low kicks with ground-and-pound. When he later won UFC 7, it wasn’t an arrival—it was a vindication of years spent quietly proving that hybrids beat purists.

🛠️ Bart Vale & American Shootfighting – Branding the Brawl Before It Had a Name

While Japan was refining shoot-style into full-fledged leagues, Bart Vale was doing something just as important in the West—he was naming it. A veteran of Japan’s UWF, Vale brought home not just techniques, but an entire combat philosophy. He began calling it Shootfighting—a bold, hybrid concept that fused strikes, submissions, and takedowns into one no-nonsense system.

Through seminars, VHS tapes, and martial arts magazines, Vale didn’t just teach techniques—he sold a new vision of fighting. One where belts, kata, and tradition took a back seat to pressure-tested realism. While his matches in Japan were often semi-worked, in the U.S., the term “Shootfighting” took on a life of its own—becoming an early stand-in for what MMA would eventually become.

Vale may not have built a league, but he built a language. And in the chaos of the early ’90s, that was power. His influence helped prep the American fight scene for what was coming: 👉 A world where mixing wasn’t just allowed—it was essential.

🔧 Matt Thornton – Aliveness, Not Dead Drills

Around the same time the first UFC shook the martial arts world, another revolution was happening quietly in American gyms. Matt Thornton, founder of the Straight Blast Gym, was challenging the traditional training methods of static drills, cooperative techniques, and kata-based repetition.

He coined the term “Aliveness”—the idea that all training should involve resistance, timing, and pressure. No more choreographed sequences. If it didn’t work under resistance, it didn’t work.

Thornton’s philosophy would shape future MMA camps like SBG Ireland (home to Conor McGregor) and reinforce a global shift: martial arts weren’t dead—just overly scripted.

🇬🇷 Jim Arvanitis & Mu-Pankration – Reclaiming the Ancient Hybrid

While Bruce Lee was forging a modern path, Jim Arvanitis was reviving an ancient one. In the early ’70s, he introduced Mu-Pankration—a modern take on the brutal Olympic-era art of Pankration, a battlefield system that combined wrestling and striking into a seamless whole.

Mu-Pankration integrated boxing, Greco-Roman wrestling, dirty-fighting tactics, and realistic sparring. Arvanitis rejected point-based competition in favour of pressure-tested realism and conditioning-based combat readiness.

Though his influence remained largely underground, he championed a critical principle:

A complete fighter must train all ranges—stand-up, clinch, and ground.

In many ways, he anticipated MMA before the acronym existed.

🇳🇱 Dutch Kickboxing – The Striker’s Hybrid Rebellion

As grapplers began studying strikes, strikers began studying pain.

In the Netherlands, a new wave of fighters blended Kyokushin Karate, Western boxing, and Muay Thai to create something entirely new:

Dutch Kickboxing—a style defined by low kicks, tight combinations, relentless pressure, and clinch knees.

Pioneers like Jan Plas, and later legends like Rob Kaman and Ramon Dekkers, redefined what functional striking looked like. Dekkers, in particular, took his Dutch system to Thailand and defeated elite Thai fighters on their own turf—proving that hybrid striking could surpass tradition, even in its birthplace.

This style laid the groundwork for modern MMA striking: You couldn’t just punch or kick anymore—you had to kick, clinch, elbow, knee, and defend takedowns—all in one rhythm.

Early pioneers like Bart Vale and Marco Ruas helped shape MMA’s hybrid style, with Vale promoting shootfighting and Ruas combining Muay Thai and grappling to dominate early competitions.

🔍 What This Era Revealed

This was the intentional turning point—the moment martial arts stopped being about tradition and started being about truth.

🧠 Bruce Lee shattered style boundaries with a philosophy of pure function over form.

⚔️ Jim Arvanitis resurrected ancient hybrid combat with modern, full-range structure.

🦵 The Dutch rewrote the striking playbook with aggression, efficiency, and hybrid discipline.

🤼 Japan’s shoot scene forged submission-heavy systems under live fire.

📜 Sayama’s Shooto laid down the rulebook before the UFC even existed.

🛠️ Bart Vale brought the hybrid mindset to American soil with Shootfighting.

🧱 Gene LeBell proved cross-training worked—decades before it had a name.

🔥 Marco Ruas became the first complete fighter before the world was ready to define one.

After decades of style-vs-style clashes and underground rivalries, a new kind of fighter began to emerge—one who wasn’t loyal to any single tradition. These pioneers didn’t care about lineage or belts. They cared about what worked. It was no longer about karate or wrestling or boxing—it was about winning fights. And that meant creating something new.

This was the age when hybrid systems were no longer accidents of experience—they became philosophies.

🇯🇵 Japan’s Early MMA Experiments

Shooto, Pancrase & RINGS

While the West was still locked in debates about tradition and Brazil was fighting bare-knuckle in underground arenas, Japan quietly began building the future of MMA. By the mid-1980s, Japanese fighters weren’t just dabbling across styles—they were developing complete systems, stress-tested in live, round-based competition. The line between striking, wrestling, and submissions blurred, and a new kind of fighter began to emerge.

Click on the links below to read more.

🥋 Shooto (1985) – The First True MMA Promotion?

Founded by Satoru Sayama, the original “Tiger Mask” of Japanese pro wrestling, Shooto was revolutionary. Sayama envisioned a combat sport built to forge complete fighters—ones who could strike, clinch, and grapple under live conditions.

Drawing from Catch Wrestling, Judo, Muay Thai, and Boxing, Shooto introduced a format that included:

- Rounds and weight classes.

- Clinching, takedowns, and ground grappling.

- Limited ground strikes.

- Unified training systems for well-rounded skillsets.

Unlike the staged theatrics of earlier shoot-style promotions, Shooto was real. Fighters trained for function, not flash. Names like Yuki Nakai and Rumina Sato became early blueprints for the modern MMA athlete: fast, flexible, and submission-savvy.

Though its global reach was limited at the time, Shooto was already simulating what the UFC would showcase years later—only it did it with structure, skill, and subtlety.

🥊 Pancrase (1993) – The Birth of the Submission-Striker

Just as the UFC prepared to launch in the US, Japan beat it to the punch with Pancrase—founded by Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki, both veterans of the UWF’s shoot wrestling tradition.

Pancrase was a paradox: raw and real, but also governed by unique rules:

- Submissions were fully legal.

- Open-hand strikes to the head only.

- Kicks, knees, and closed-fist body shots allowed.

- Rope escapes instead of tap-outs (in early events).

These rules created a strategic, cerebral fight style where technique reigned over brawling. And from this crucible emerged future legends:

- Bas Rutten, the liver-kicking, guillotine-snatching Dutch destroyer.

- Ken and Frank Shamrock, whose balance of wrestling, striking, and submission control redefined well-roundedness.

Pancrase blurred the line between performance and combat, but its fighters would go on to dominate real MMA. The discipline honed here became the DNA of elite-level competition.

🧬 RINGS (1991) – Grappling’s Evolution Lab

While Pancrase focused on balanced hybrids, RINGS—founded by Akira Maeda—became a haven for submission artistry.

Originally a pro wrestling offshoot, RINGS quickly evolved into a globally scouted, tournament-based arena that drew elite grapplers from Russia, Europe, and Japan. It favoured:

- Clinch control and takedowns.

- Ground transitions and submission chaining.

- Minimal striking in favour of tactical grappling flow.

Key figures defined the league:

- Volk Han, with his wrist locks, leg entanglements, and smooth positional dominance—years ahead of the No-Gi curve.

- Fedor Emelianenko, quietly sharpening his game in RINGS before his reign of terror in PRIDE.

- Kiyoshi Tamura, a grappling genius with striking finesse and unmatched transitional fluency.

RINGS may have lacked flash—but it overflowed with depth. It became the proving ground for the most technically complete submission fighters of the era, directly shaping the next evolution of grappling in MMA.

🥋 Innovators from Shooto, Pancrase & RINGS That Defined Early MMA

A deeper look into Japan’s martial arts scene during this era reveals a cast of underappreciated innovators—fighters who embodied the hybrid spirit before the world had a name for it.

Beyond the big names, these athletes took the philosophies of Shooto, Pancrase, and RINGS and pushed them into uncharted territory. They blurred lines between spectacle and substance, performance and pressure-tested skill—proving that the Japanese fight labs of the 1990s weren’t just ahead of their time, they were already producing the future of MMA.

🇯🇵 Japanese Technicians

- 🥋 Genki Sudo – A martial artist as philosopher and performer. Wildly unorthodox, yet deadly with submissions and strategy. He showed that flair and function could coexist.

- 🛡️ Enson Inoue – A warrior in every sense. Fought for honour, not hype. His crossover bouts and spiritual approach gave MMA a deeper code of conduct.

- 🐍 Ikuhisa Minowa (“Minowaman”) – A giant-slayer with real catch-wrestling skills. He blurred the line between spectacle and skill, fighting with heart and technique against the odds.

🇷🇺 Sambo Grapplers Beyond Fedor

- 🧬 Volk Han – A submission artist from RINGS whose fluid, advanced grappling influenced a generation long before BJJ caught up.

- 🧊 Mikhail Ilyukhin – A less-heralded Sambo technician who helped prove that the Russian submission game wasn’t just Fedor’s domain.

🥊 American & International Heavyweights (Non-Gracie)

- 💣 Tom Erikson – The wrestling powerhouse who showed both the strengths and limits of pure wrestling in MMA.

- ⚔️ Dan Severn – One of the earliest UFC champions. His dominance paved the way for wrestling’s rise in mainstream MMA.

🌍 Global Unheralded Pioneers

- 🥇 Igor Vovchanchyn (Ukraine) – A pre-Fedor hybrid fighter with KO power and underrated grappling. Fought anyone, anywhere, and finished them.

- 🐐 José “Pelé” Landi-Jons (Brazil) – A raw, aggressive striker from the Chute Boxe school who brought chaos and Muay Thai fury to the early Vale Tudo scene.

Early MMA promotions like Shooto, founded in Japan in 1985 by Satoru “Tiger Mask” Sayama (left), helped lay the groundwork for modern mixed martial arts. Bas Rutten (right) rose to prominence in Pancrase during the 1990s, showcasing a dynamic striking and submission style that made him one of the first well-rounded fighters in MMA history.

🇯🇵 Why Japan Mattered

Japan didn’t just experiment with cross-training—it created the blueprint for structured mixed combat:

- Shooto introduced the rule set.

- Pancrase proved strikers and grapplers could evolve together.

- RINGS refined grappling systems under live, elite-level pressure.

These weren’t backyard brawls or theoretical debates. They were functional fight systems, years ahead of their time.

While the West was still asking,

“Which style is best?”

Japan had already moved on to the real question:

“What happens when you train for all of them—and test it under fire?”

🇺🇸 The Pre-UFC American Underground

(1980s–Early 1990s)

Before the Octagon, before gloves and weight classes, there was a moment when American MMA almost broke through—then vanished into legal shadow. In smoky auditoriums and gritty gyms, rogue events tested raw combat potential, blending styles without safety nets. It was unsanctioned, unrefined, and undeniably real. But when tragedy struck, the crackdown came fast—shutting the door just as it was opening. This section dives into the forgotten era that nearly birthed MMA in America before the UFC made it official.

Click on the links below to read more.

🥊 Tough Guy Contests – MMA Before It Had a Name

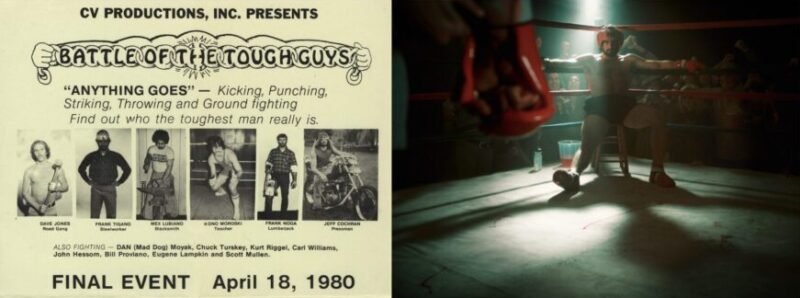

In 1980, a Pennsylvania-based outfit called CV Productions launched what might be the world’s first officially promoted no-holds-barred event: the Tough Guy Contest.

- Fighters came from all walks—karate, boxing, wrestling, barroom brawling.

- The format was open-weight, bare-knuckle, and fast-paced.

- Protective gear was minimal, medical oversight even more so.

The events gained traction quickly. But as other promoters copied the format with looser standards, the cracks began to show. Tragedy struck during a non-CV affiliated “Toughman” contest, where a participant died from injuries sustained in the ring.

In response, Pennsylvania passed a law banning all unsanctioned martial arts contests, effectively ending America’s earliest flirtation with organised MMA before it could evolve.

🔗 Shootfighting Comes Stateside

Even as regulators shut the door on Tough Guy events, another wave of hybrid combat was quietly arriving from Japan.

Trained under Satoru Sayama’s Shooto system, pioneers like Erik Paulson brought a new formula to the U.S.—blending submission grappling, Catch Wrestling, and kickboxing into a fluid, all-ranges fighting approach. Fighters like Bart Vale also helped spread Japanese shoot-style methods, teaching techniques that would one day become cornerstones of MMA.

These weren’t brawlers—they were technicians, laying the groundwork for what would become a full-contact, strategic evolution of American martial arts.

Tough Guy Challenges, held in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the United States, were among the first organised attempts to pit different fighting styles against each other under limited rules. Though largely unregulated and later banned, these early events helped lay the cultural foundation for the creation of modern MMA by testing real-world effectiveness across styles.

🇺🇸 Why It Mattered

The American underground era proved two crucial things:

- There was demand for unfiltered, real combat.

- There was danger without regulation.

These raw events were short-lived, but they forced U.S. promoters to rethink the formula. Blood alone wasn’t enough—structure was required for survival.

The lessons learned would shape the future of MMA in America:

- Time limits.

- Weight classes.

- Gloves and medical checks.

- Athletic commissions and sanctioning bodies.

Ironically, it was the crackdown that gave MMA its future. What began in backroom brawls and outlaw contests would eventually evolve into one of the world’s most tightly structured combat sports.

🔍 Lessons from Cross-Disciplinary Combat

By the late 1980s, the martial arts world had undergone a trial by fire. The style-vs-style clashes of the past decades had shattered illusions, exposing hard truths: no art was complete, and tradition alone no longer guaranteed survival. Fighters once proud of their lineage were suddenly forced to evolve—or disappear.

Click on the links below to read more.

❌ Strikers Without Grappling Were Sitting Ducks

Boxers and karatekas who couldn’t defend a takedown were dragged into deep water and submitted. It didn’t matter how sharp their hands were—if they couldn’t fight on the ground, they never got to fight at all.

❌ Grapplers Without Takedowns Were Helpless at Range

Judokas and wrestlers who couldn’t close the distance got picked apart. Without the ability to shoot, clinch, or feint behind strikes, they were punching bags at range—unable to start the fight on their terms.

❌ No Single Art Had All the Answers

- Karate had precision—but lacked adaptability.

- Boxing had power—but no clinch or ground game.

- Judo had throws—but struggled in scrambles and submissions.

- Wrestling had control—but no finishing mechanics.

- BJJ had ground mastery—but limited striking and takedowns.

- Muay Thai had savagery—but was vulnerable on the mat.

Even the most respected systems had glaring gaps.

🧭 The Path Forward Was Clear: Adapt or Be Obliterated

Across Brazil, Japan, the Soviet Bloc, and America’s underground circuits, a new lesson was taking root: no fighter could afford to be one-dimensional anymore.

Those who cross-trained—survived and thrived.

Those who clung to purity—vanished.

Martial arts were no longer rigid systems—they were becoming modular toolkits.

- Fighters began blending striking and grappling.

- Promotions began building unified rules to test complete skillsets.

- Gyms shifted toward training across all ranges—stand-up, clinch, ground.

This was no longer a philosophical shift.

It was an evolutionary one.

The only question that remained was this:

What happens when we throw all these systems into one cage—and lock the door?

That answer was coming.

And the Gracie family was about to give it to the world.

The Birth of the UFC (1993)

In the shadow of martial arts cinema and point-fighting tournaments, a quieter revolution was brewing. The mystique of invincible styles was about to be tested—not on movie sets, but in a steel cage under bright lights. There were no scripts, no stunt doubles—just sweat, blood, and consequence. When the Octagon was unveiled in 1993, it wasn’t just a stage—it was a crucible. What happened inside would expose truth, dismantle fantasy, and force the entire fight world to evolve.

Click on the links below to read more.

🎲 The Gracie Gambit

By the early 1990s, the Gracie family had already carved a reputation in Brazil’s Vale Tudo arenas—proving time and again that leverage, positioning, and submission could topple brute strength and striking alone. But their dominance—raw, brutal, and undeniable—remained a local legend, unknown to the wider world. For Rorion Gracie, the eldest son of Hélio and a man with a vision, that wasn’t good enough.

After relocating to California in the 1970s, Rorion began quietly building a movement—teaching Jiu-Jitsu in garages, hosting backyard challenge matches, and training law enforcement in close-quarters control. But his mission wasn’t just to teach—it was to prove. Fuelled by the legacy of no-rules challenge matches that had defined the Gracie name, Rorion envisioned something bigger: a televised, no-rules tournament that would settle the age-old question—what really works in a fight?

No weight classes. No time limits. No gloves. Just raw, unfiltered combat.

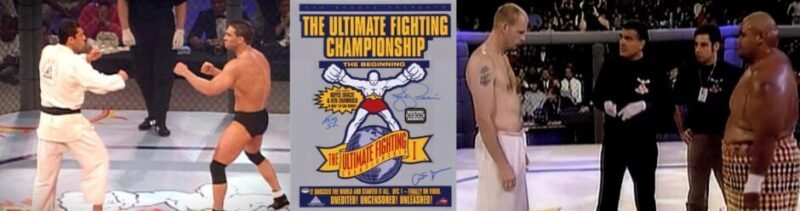

In 1993, that vision found a business partner in Art Davie, an advertising executive with a flair for spectacle. Together with Semaphore Entertainment Group (SEG), led by Bob Meyrowitz, they turned the idea into a reality. The Ultimate Fighting Championship was born—a one-night, eight-man tournament designed to showcase not just fighters, but philosophies.

But it wasn’t just a showcase.

It was a trap, meticulously laid.

Rorion hand-picked his younger brother, Royce Gracie, to represent Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu—not because he was the strongest, but because he wasn’t. Slender, calm, and unassuming, Royce was there to make a point. When he stepped into the Octagon at UFC 1 wearing a white gi and weighing just 180 pounds, he wasn’t defending a style—he was executing a plan. Calm, coiled, and clinical, he would change the fight world forever.

🛡️ The Setup: UFC 1 (November 12, 1993)

📍 Location: Denver, Colorado

👊 Format: One-night, eight-man tournament

📏 Rules: No gloves, no rounds, no weight classes

🥋 Fighters: Boxers, karatekas, kickboxers, shootfighters, sumo wrestlers, and one quiet Brazilian wearing a gi

Hand-picked by Rorion not for flash, but for philosophy.

Royce Gracie stood in stark contrast to his opponents—thin, calm, and composed. He wasn’t just there to win. He was there to redefine what winning looked like.

💥 The Aftershock: A New World Begins

Royce Gracie dominated the tournament, submitting every opponent—including Art Jimmerson (Kenpo), Ken Shamrock (Shootfighting), and Gerard Gordeau (Savate)—without taking significant damage.

The martial arts world was stunned.

A fighter who didn’t throw a single punch had dismantled every striker in the building.

🔒 Ground control and submissions were now undeniable

🧠 Fighters realised their styles were incomplete

⚔️ Traditionalists could no longer claim superiority without proof

This wasn’t a fluke. It was the beginning of a new era.

The UFC didn’t just birth a promotion.

It forced an entire industry to evolve.

The Gracie Challenge had gone global—

and this time, the whole world tapped.

UFC 1, held in 1993, was a turning point for the martial arts world, showcasing real, unscripted style-versus-style combat for a global audience. Its success exposed the limitations of traditional martial arts in full-contact fighting and set the stage for the evolution of MMA into a fully integrated combat sport.

🧭 Summary

The End of Purity, the Dawn of Integration

The years leading up to UFC 1 marked the end of martial arts as isolated traditions and the beginning of their transformation into fully integrated combat systems. From the back-alleys of Brazil to Japan’s shoot leagues and Soviet grappling pits, one truth echoed louder with every clash: no single style could meet the total demands of unarmed combat.

As fighters encountered new threats—striking, clinch, takedowns, submissions—they were forced to evolve. Hybrid systems emerged not from theory, but necessity, forged in the chaos of real-world violence and stripped of tradition’s illusions.

🧩 From Fragmented Styles to Functional Systems

- Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu taught control and submission.

- Sambo added throws, pressure, and grit.

- Catch Wrestling and Shootfighting unlocked transitions and chains.

- Muay Thai and Dutch Kickboxing redefined striking for MMA’s future.

Organisations like Shooto, Pancrase, and RINGS introduced structure to the chaos, crafting the first true proving grounds for cross-disciplinary fighters. By the early 1990s, the question wasn’t “Which style is best?” It was:

“How do I train for everything?”

The UFC didn’t create MMA.

It simply revealed what decades of unsanctioned trials had already proven:

👉 Effectiveness in combat demands adaptation.

👉 Victory belongs to the well-rounded.

👉 The modern fighter is not a stylist—they’re a strategist.

The age of purity was over.

The arms race had begun.

Adapt—or get left behind.

Combat Evolution

What Endures ⚔️ 🤼 👊🏼

The road to Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) was paved with decades of cross-disciplinary experimentation and combat innovation. From the first Vale Tudo fights in Brazil to the fusion of Judo and Catch Wrestling in Japan, martial artists constantly tested their techniques against one another, seeking to prove that no single martial art could dominate. These early hybrid contests set the stage for the evolution of modern combat sports, leading to the birth of MMA in the 1990s. The foundational ideas of adaptability, cross-training, and hybrid techniques that arose from these experiments continue to shape both combat sports and real-world self-defence training today.

📌 Cross-Training & Hybrid Combat

The idea of cross-training and blending techniques from various combat systems became a cornerstone of modern MMA. Early style vs. style matchups—such as Judo vs. Jiu-Jitsu and Boxing vs. Karate—exposed the limitations of single-discipline training and highlighted the need for well-rounded fighters. This period marked a shift from rigid adherence to a single martial art towards a more integrated approach, where strikers and grapplers began incorporating techniques from multiple disciplines. The Gracie family’s dominance in Vale Tudo and the early UFCs demonstrated the effectiveness of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ), but as competition evolved, the need for fighters to adapt and master both striking and grappling became clear. This trend led directly to the modern MMA philosophy, which now emphasises cross-training in striking, grappling, and defence.

📌 The Importance of Adaptability

Adaptability emerged as one of the key themes of combat evolution during this period. Fighters quickly learned that relying on a single fighting style left them vulnerable to specialists in other disciplines. For example, Karate fighters—trained for striking—struggled when forced to face off against grapplers, while wrestlers had to develop striking techniques to keep up with their opponents. This drive for adaptability led to the rise of hybrid systems such as Jeet Kune Do (JKD), Mu-Pankration, and early Kickboxing, which combined boxing, wrestling, and traditional martial arts into versatile combat systems. Fighters were now trained to adapt their techniques to different combat scenarios, learning to integrate strategies from across martial arts styles.

📌 Psychological Warfare & Mental Conditioning

Psychological warfare became a significant component of combat sports during this era. Bruce Lee’s philosophy of “Absorb what is useful” and his focus on mental agility encouraged fighters to constantly adapt and evolve their techniques. This mindset influenced the mentality of modern fighters, where psychological tactics, including feints, deception, and controlled aggression, are critical to success. The importance of mental conditioning was evident in the early UFC, where fighters who could maintain composure under pressure dominated. The blend of mind and body was recognised as essential, influencing not only modern MMA but also military training programs, where mental toughness and the ability to adjust tactics in the heat of battle are paramount.

📌 Transmission of Martial Knowledge & the Rise of the UFC

As martial arts spread globally, there was a marked shift in how martial knowledge was transmitted. Early cross-disciplinary matches and self-defense challenges paved the way for the structured tournaments and competitions we see today. Early Vale Tudo contests in Brazil were often unsanctioned, no-rules affairs that tested the effectiveness of grappling against striking. These events not only showcased the limitations of single martial arts but also emphasised the need for structured competition to separate practicality from theory. The rise of Shooto, Pancrase, and RINGS in Japan, alongside the Gracie family’s open challenges, proved the concept of hybrid combat, where fighters from different backgrounds would come together in an open environment to test their combat skills. This eventual lead to the creation of the UFC in 1993, providing a global stage for fighters to prove the effectiveness of their styles, culminating in the cross-training mindset we see in MMA today.

📌 The Rise of Full-Contact Combat & the End of Point Fighting

Before the development of MMA, traditional Karate and Boxing competed in point-based tournaments, which focused on clean, controlled strikes. As fighters began to realise that point-based fighting didn’t prepare them for real-world combat, the focus shifted to full-contact, allowing for continuous exchanges, knockout finishes, and uninterrupted striking. The emergence of Kickboxing in the 1970s and its emphasis on leg kicks, clinch control, and high-volume striking proved that traditional stand-up fighting systems needed to evolve in order to stay relevant. This evolution led directly to the striking-focused aspects of modern MMA, where clinch fighting, knee strikes, leg kicks, and elbows became integral components of stand-up combat. This shift in focus ultimately blurred the lines between striking arts and grappling systems, setting the stage for hybrid styles that combined the strengths of both.

Timeline 🕰️📈

| Date | Development/Technique/Event | Region | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920s–1930s CE | Judo vs. Jiu-Jitsu Rivalry: Mitsuyo Maeda and the Gracies refine ground-fighting techniques. | Brazil | Laid the foundation for Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ). |

| 1920s–1990s CE | Vale Tudo ("Anything Goes") Fights: No-rules fights between different martial arts styles. | Brazil | Created an early no-holds-barred format, influencing modern MMA. |

| 1920s–1950s CE | Catch Wrestling vs. Judo: Hybrid grappling contests emerge in Japan and the West. | Japan, USA, UK | Pushed the evolution of submission-based fighting. |

| 1963 CE | Gene LeBell (Judo) vs. Milo Savage (Boxing): First televised mixed-style fight. | USA | Demonstrated effectiveness of grappling against pure strikers. |

| 1967 CE | Bruce Lee Founds Jeet Kune Do (JKD): Early hybrid martial art blending multiple styles. | USA | Influenced modern MMA philosophy with “Absorb what is useful.” |

| 1969 CE | Modern Pankration Reconstructed: Jim Arvanitis revives ancient Greek pankration. | USA/Greece | Contributed to hybrid martial arts and MMA development. |

| 1973 CE | Enter the Dragon Released: Bruce Lee’s film sparks global martial arts interest. | USA, Hong Kong | Brought Kung Fu and hybrid martial arts to mainstream audiences. |

| 1975 CE | Tao of Jeet Kune Do Published: Bruce Lee’s writings on cross-training and hybrid techniques. | USA | Encouraged the integration of multiple martial arts styles. |

| 1976 CE | Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki: Boxer vs. Wrestler mixed-rules fight. | Japan | Early test of striking vs. grappling; influenced Japanese MMA development. |

| 1980s CE | Early Toughman & Shootfighting Events: Unregulated hybrid fights take place in underground circuits. | USA, Japan | Showed public interest in real fighting; inspired future MMA competitions. |

| 1985 CE | Shooto Founded by Satoru Sayama: Shoot-wrestling organisation promoting real fights. | Japan | Considered the first true mixed martial arts promotion. |

| 1980s–1990s CE | Luta Livre vs. BJJ Rivalry: No-Gi vs. Gi conflict leads to Vale Tudo clashes in Brazil. | Brazil | Pushed the evolution of submission grappling and MMA’s ruleset. |

| 1991 CE | RINGS Founded: Early shootfighting organisation in Japan. | Japan | Developed hybrid striking-grappling combat before modern MMA. |

| 1993 CE | First UFC Tournament: Royce Gracie wins using Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu against various styles. | USA | Established BJJ’s dominance and led to the evolution of MMA training. |

Our next post dives into the explosion of MMA as a global sport—how the UFC’s rise, rule changes, and international promotions transformed it from a brutal experiment into the ultimate combat discipline.