From Brazil’s vibrant streets to global stages, explore Capoeira, a unique blend of martial art, dance, and cultural defiance that captivates fighters and free spirits worldwide.

Table of Contents

Introduction

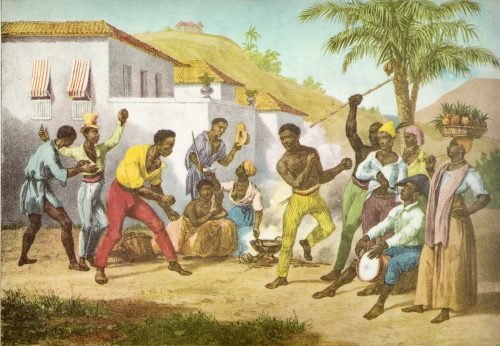

Capoeira is an Afro-Brazilian martial art that combines elements of dance, acrobatics and music. The basic elements of capoeira were brought to South America by enslaved people, primarily from western and central Africa. Eventually, the techniques travelled from Bolivia to Brazil via transported slaves. Over the centuries that followed these elements were practised and reimagined within the diverse enslaved community of Brazil. New techniques were developed and the art became unique. Resulting in a unique means of self-defence, both driven and disguised as a dance with musical accompaniment. Capoeira is famed for its acrobatic and complex manoeuvres, often involving hands on the ground and inverted kicks.

History

Click on the links below for more.

Early Origins - Out of Africa

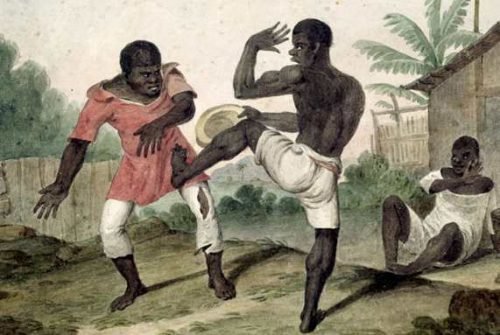

There are a number of theories attempting to explain the origins of Capoeira, all of which have some degree of truth. The original version of the system is thought to have developed from various African cultures and traditions.

One theory speculated that the Mucupes of South Angola (part of the Bantu tribe) sowed the seeds for what would become Capoeira. The Mucupes had an initiation ritual (efundula) for when girls became women. During these occasions young warriors would engage in the ‘N’golo/Engolo’ (Dance of the Zebras) which was a kind of warrior’s fight-dance.

The Mucupes were among many other African tribes affected when their cultures and traditions were uprooted during the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade. The transatlantic slave trade was an oceanic trade in African men, women, and children which lasted from the mid-sixteenth century until the 1860s. European traders loaded African captives at dozens of points on the African coast. These slaves were taken to colonies in the Americas and forced to work in sugar cane fields.

The disenfranchised Mucupes (and other African tribes) bought their unique cultural knowledge with them to the Americas. It included not only knowledge of warrior dances (such as the Engolo) but also of religion, music (the berimbau), food and attitudes. This was an oral tradition (passed on by word of mouth rather than written down) of the engolo and other warrior traditions. These traditions were kept alive, transmitted and shared over generations.

This theory was originally presented by Camara Cascudo (folclore do Brasil, 1967). However, a year later Waldeloir Rego (Capoeira Angola, Editora Itapoan, Salvador, 1968) warned about the lack of evidence to support these claims and invited more research on the matter (sadly no one ever did follow the research up.) It is likely that if Engolo did exist, it would seem that it was at best one of several African dances/traditions that contributed to the creation of early versions of Capoeira.

The traditions transferred around the Americas and in time the techniques found their way to (Portuguese-occupied) Brazil via transported slaves.

Disguised as Dance

The Engolo and other African warrior traditions were practised by many of the slaves over the years. Many slaves used it to help defend themselves against their (often) brutal overlords. Some practiced it to build their survival skills for the day that they would escape their servitude. Being on the run with no weapons they would need all the advantages in combat they could get.

Since slaves would be punished severely if they were seen to be practising any kind of self-defence they needed to conceal what they were doing. They did this by disguising the ‘fighting’ as dance moves performed to music. In the dance, one performer played the slave and the other, the ‘master’. During this performance, the slave defended himself against the master. For the early slaves, the practice of dance was a way of connecting with the culture that they had lost connection with.

Click on the links below for more.

Quilombos

In 1602 Portugal went to war with the Dutch. The conflict primarily involved the Dutch companies invading Portuguese colonies in the Americas, Africa, and the East Indies. This conflict was to some degree to the advantage of the slaves. Every time the Dutch would invade, the security of the plantations and towns was weakened. The slaves took full advantage of the opportunities and would flee into the forests in search of places in which to hide and survive. Many of those who escaped founded independent villages called ‘Quilombos’.

The quilombos were often established in far and hard-to-reach places for reasons of security. Places any pursuing authorities were unlikely to look. Over time, some quilombos attracted large quantities of fugitive slaves. They were often multi-ethnic societies including Brazilian natives and even Europeans escaping the law or Christian extremism. Many of the quilombos became large in scale. There were at least ten major quilombos with internal socio-economic organisations. Some of the quilombos also had commercial relationships with neighbouring cities. The biggest quilombo, the Quilombo dos Palmares, consisted of many villages which lasted almost a century before its eventual suppression.

Guerilla fighters

Over time it became a necessity for the quilombos to be able to defend themselves effectively. This was due to the constant threat from the authorities not wanting rogue states on their doorsteps. Furthermore, the authorities wanted to recapture escaped slaves who were still perceived as fugitives.

Over time the quilombos inhabitants developed as effective and deadly guerilla fighters. Armed with whatever weapons they could lay their hands on (spears, bows, arrows and guns) they defended their land. They were able to acquire guns by trading with the Portuguese. The inhabitants of Palmares, familiar with the terrain, utilised camouflage and guerilla techniques, specialising in ambush and skirmish tactics. The Palmares encampments were well fortified by the use of fences, walls, and traps and so were difficult for the authorities to attack.

There is much debate about how much Capoeira was used in staving off the attacks of the Portuguese authorities during this period. With some claiming that it was used to defend against heavily armed and armoured mounted troops. This seems highly unlikely. It is more likely that the quilombos developed a range of guerilla fighting techniques for many eventualities. Hand-to-hand fighting (Capoeira) in this case would have been a highly valuable tool if quilombos found themselves without a weapon.

Regardless, the quilombos were still very important to the evolution of Capoeira. Indeed, the most widely accepted origin of the word ‘Capoeira’ comes from the Tupi words ka’a (forest) paũ (round), referring to the areas of low vegetation in the Brazilian interior where fugitive slaves would hide. Away from the eyes and oppression of the colonial authorities, capoeira practitioners were able to develop the art. New techniques and methods were added with practice and study. Everyday life in the quilombo offered freedom and the opportunity to revive traditional arts and develop new ones. Once Capoeira did return from exile to the streets of Brazil, it was a completely evolved fighting art.

Click on the links below for more.

Suppression of Capoeira

Over the centuries that followed, Capoeira (as it was now known) continued to be practised and evolved. This was both in the cities of Brazil and in the quilombos settlements in the jungles. Around the beginning of the 18th century, Brazil’s economy experienced a boom. Due to city growth, more slaves were brought to cities to deal with the expanding workload. The increase in social life in the cities made capoeira more prominent there. This resulted in it being taught and practised among more people. Registries of capoeira practices existed since the 18th century in Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Recife. However, things would change with the arrival in Brazil in 1808 of the Portuguese king Dom Joao VI and his court.

The King was fleeing Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Portugal. Being a ruler of a somewhat fragile and crumbling kingdom, Dom Joao looked at his colony and must have felt threatened. He had lost his country to the invading French and all he had left were the colonies still under Portuguese authority. The slaves and natives would have outnumbered his forces in Brazil. Therefore like any ruler, at the time he decided to show them who was in charge. Dom Joao understood the necessity of destroying a people’s culture in order to dominate them. During his time in Brazil, many forms of African cultural expression suffered repression.

Since capoeira was often used against the colonial guard, the government introduced severe physical punishments to anyone practising it. This included hunting down practitioners and killing them openly. There were other motives for Capoeira to be prohibited. It gave the slaves a sense of unity and belonging and gave self-confidence to individual practitioners. It also created dangerous and agile fighters. Additionally, on occasion, a slave would injure themselves practising Capoeira, something that was not desirable from an economical point of view.

There is much data from police records from the 1800s shows that many slaves and free people were detained for practising capoeira:

‘From 288 slaves that entered the Calabouço jail during the years 1857 and 1858, 80 (31%) were arrested for capoeira and only 28 (10.7%) for running away. Out of 4,303 arrests in Rio police jail in 1862, 404 detainees—nearly 10%—had been arrested for capoeira.’

The Golden Law and the Gangs of Rio

Things changed in 1888 when the Golden Law (Lei Áurea) was signed effectively abolishing slavery in Brazil. This all sounds well and good, however free former slaves now felt abandoned. The newly freed slaves did not find a place for themselves within the existing socio-economic order. The majority of them had nowhere to live and no jobs. New immigration from Europe and Asia left most former slaves with no employment.

Furthermore, they for the most part were despised by Brazilian society, which typically viewed them as worthless, lazy workers. For the average capoeirista, this left them with no job, no prospects, no income and potential to better themselves. All they possessed were their fighting skills and self-confidence.

Soon the capoeiristas began to use their skills in unconventional ways. The criminal underclass began to hire them as bodyguards, enforcers and hitmen. In Rio de Janeiro, criminal gangs were created that terrorized the population. During the political turmoil of the transition from the Brazilian Empire to the Brazilian republic in 1890. During this period these gangs were used by both monarchists and republicans to exert pressure on and break up the rallies of their adversaries. On the streets of Rio, weapons such as the club, the dagger and the switchblade were used by capoeiristas with deadly effects.

Regardless of ethnicity (black, white or mulatto) most criminals were skilled in some form of Capoeira street fighting. They were well versed in the use of kicks (golpes), sweeps (rasteiras) and head-butts (cabecadas), as well as in the use of blade weapons. In Recife, Capoeira became associated with the city’s principal music bands. During carnival time, tough young Capoeira fighters would lead the bands through the city streets. Whenever two bands would meet, fighting and bloodshed would usually ensue. The persecution and the confrontations with the police continued, eventually leading to Capoeira’s practice being outlawed in 1892. In the years following the art form slowly began to become extinguished in Rio and Recife, leaving Capoeira only in the Bahia region. This continued right through the beginning of the 20th century.

During the era of the gangs of Rio, Capoeiristas were known only by their nicknames. This made it more difficult for the police to identify and arrest them since their real identities were unknown.

Click on the links below for more.

Capoeira Schools

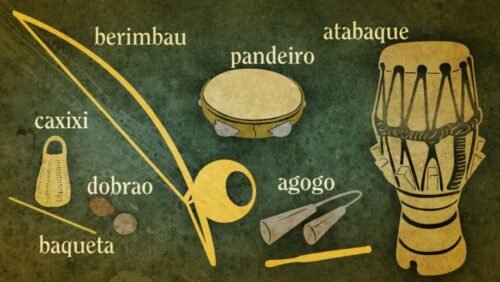

In Bahia on the other hand, Capoeira continued to develop into a ritual dance/fight game of its origins. Music began to play a more central role in the practice of Capoeira. The berimbau began to be an indispensable instrument used to command the rodas (actual sessions of Capoeira games). However, due to the outlawing of its practice, Capoeira sessions always took place in hidden locations. Away from the authorities.

By the 1920s, Capoeira repression had declined. Several practitioners helped generate interest in Capoeira to a wider audience by teaching variations of the art or writing manuals. These included Professor Mario Aleixo, Anibal ‘Zuma’ Burlamaqui; Inezil Penha Marinho, Felix Peligrini and Mestre Sinhozinho. However, when it comes to the modern pioneers of the art there are two very important Capoeira ‘Mestres’ (masters). Mestre Pastinha and Mestre Bimba.

Mestre Bimba

In 1932 in Salvador, Mestre Bimba (aka Manuel dos Reis Machado) a traditional capoeirista opened the first Capoeira academy. He started teaching what he called ‘Luta Regional Baiana’ (the regional fight from Bahia). Bimba used this name because Capoeira was still illegal to practice so it had to be labelled something else. In time, however, this eventually became known as ‘Capoeira Regional’ (a style that was faster and more aggressive than the traditional Capoeira Angola style). Although Bimba opened his school in 1932, the official recognition only came about in 1937.

Bimba’s effort was helped dramatically by the nationalistic policies of Getulio Vargas. Vargas was a Brazilian lawyer and politician who served as Brazil’s 14th and 17th president. It was Vargas’s intention to promote Capoeira as a Brazilian sport. It was Mestre Bimba’s efforts that eventually brought Capoeira Regional to the masses. By 1936, capoeira had finally lost its criminal connotation; it was officially recognized by the Brazilian government and was legalised. Mestre Bimba was invited by the government to perform Capoeira for president Vargas. Many consider Mestre Bimba ‘the Father of modern Capoeira.’

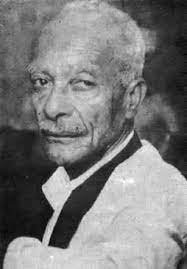

Mestre Pastinha

Mestre Pastinha (aka Vincente Ferreira) is known as ‘the father of Capoeira Angola’. Mestre Pastinha was one of a number of mestres who thought that Capoeira was losing its way. They saw the old ways of training as more authentic to the true spirit of Capoeira. In the past Capoeira was learned by observation and imitation. Participants witnessed capoeira in rodas and learnt by copying and practicing what they saw. Pastinha wanted to go back to these raw traditions. Additionally, Pastinha felt that improvisation and malicia were the trademarks of original Capoeira. He wanted more focus on these deceptions and tricks in his version of Capoeira as opposed to acrobatics and high flying kicks.

In time, Pastinha founded the Centro Esportivo de Capoeira Angola (CECA). Located in the Salvador neighbourhood of Pelourinho. This school attracted many traditional capoeiristas. With CECA’s prominence, the traditional style came to be called Capoeira Angola. That name is derived from ‘Brincar de Angola’ (playing Angola), a term used in the 19th century in some places.

Despite Pastinha’s work in preserving traditional Capoeira, he came to an unfortunate end. Betrayed by local authorities, his academy was confiscated by them, with promises of renovation. However, the renovated space was then given to a restaurant. Mestre Pastinha was left abandoned in a city shelter in Salvador. He died in November 13, 1981, aged 92 as a poor, blind and bitter man.

Mestre Bimba.

Mestre Pastinha.

Characteristics of Capoeira

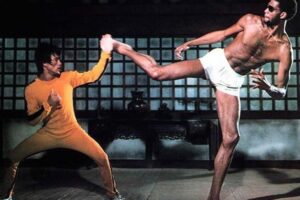

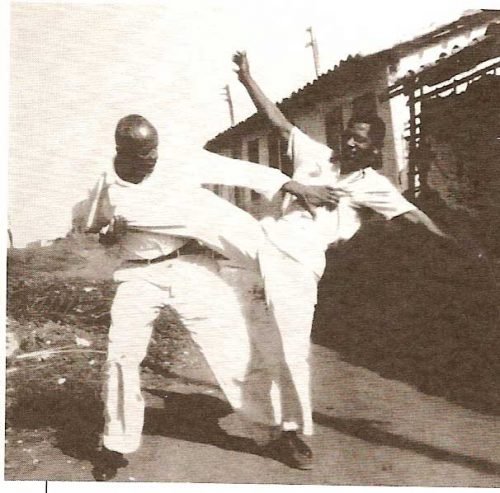

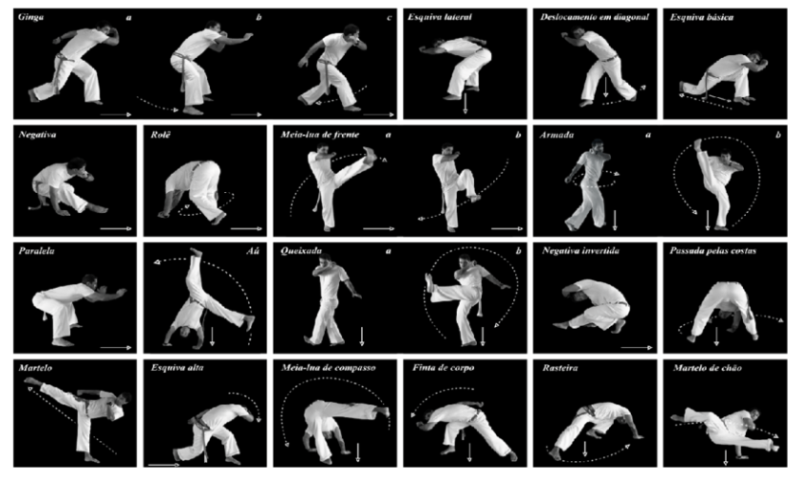

Capoeira is a fast and versatile martial art with a focus on fighting outnumbered or being at a disadvantage. The fundamental movement of capoeira is the Ginga. This can only be described as a ‘moving stance’ and is unlike anything found in other martial arts systems. The Ginga involves having both feet shoulder width apart, practitioners move one foot backwards and then back to the base. This is then repeated with the alternate leg. The movement is a somewhat triangular and rhythmic step.

The Ginga is very important both for attack and defence purposes, having two main objectives. The first is to keep the capoeirista in a state of constant motion. This prevents the capoeirista from being an easy target. The second objective of the Ginga is to allow fakes and feints. This has the aim of misleading or following an opponent, leaving them open for an attack or a counter-attack.

The Ginga is a type of ‘moving stance’ used in Capoeira to keep the user in perpetual motion. This enables the fast chaining together of kicks or evasions.

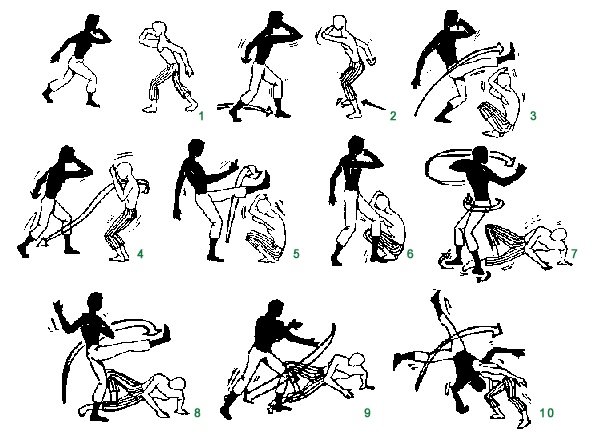

Offensive Strategies

Capoeira is very much about timing and seeking openings and opportunities to attack. Attacks (often preceded by feints or deceptions known as ‘malicia‘) must be precise and decisive strikes or takedowns. The majority of capoeira attacks are made with the legs. They rely heavily on direct or swirling kicks, leg sweeps (rasteiras), and scissor-like takedowns (tesouras). Other kicks in Capoeira include variations of roundhouse kicks; sidekicks; front stomping kicks; low kicks; high turning kicks; and outside and inside crescent kicks. The head strike is also an important counter-attack move used in capoeira. Historically speaking there is a good reason why punching and grappling are not very prominent in Capoeira. Very often the slave’s hands were manacled which made hand strikes very difficult. As such the slaves had to adapt and learn to defend themselves without the use of their hands. However, in modern practice elbow strikes and several hand strikes are utilised. Although this is mainly to feint and set up powerful kicks and takedowns. Additionally, many Capoeira moves involve the use of hands on the floor to support kicks and evasions.

Capoeira is a martial art full of swirling and acrobatic style kicks and leaps.

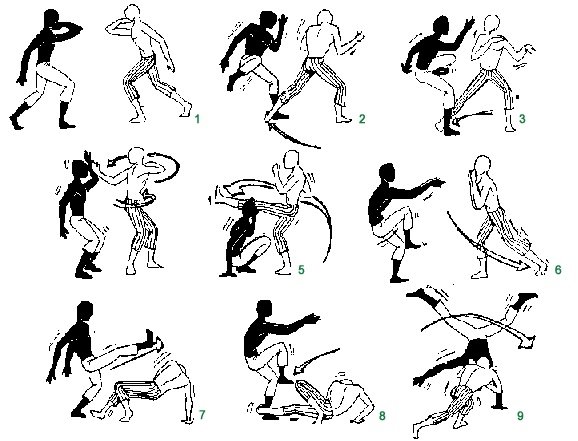

Defensive Strategies

Defence in Capoeira is based on the principle of non-resistance. Attacks are avoided using evasive moves instead of blocking them. This tradition stems from necessity. Manacled slaves would risk death if they tried to block bladed attacks from their captors. From their experiences, they found it was far better to utilise evasive manoeuvres. The emphasis is for the capoeirista to be in constant motion, thus preventing them from being a still and easy target. Evasive moves (known as ‘esquivas‘) include rolls, cartwheels, and acrobatics. These enable the fighter to evade an attack or close the distance quickly for a counterstrike. Capoeira involves great unpredictability, reflexes, flexibility and speed.

Esquivas (evasions) allow the Capoeirista to avoid the attacks of their opponents.

Weapons Use

Certainly, throughout its later history in Brazil, capoeira commonly featured weapons and weapon training. This is understandable given its violent background of fighting oppressors in the streets and jungles. Although the slaves had limited access to weapons like many martial arts they improvised with what was at hand. The tools the slaves used in the fields became the weapons of Capoeira. These included the sugar cane knife and the 3/4-inch staff. Later on in the 1800s, Capoeirista gang members would carry knives and bladed weapons with them. They often would conceal these weapons in everyday items to hide them from the eyes of the authorities. The berimbau could be used to conceal them and could also be turned into a weapon by attaching a blade to its tip. The knife or razor was used in street rodas and/or against openly hostile opponents and would be drawn quickly to stab or slash. Other hiding places for the weapons included hats and umbrellas.

The traditional weapons of Capoeira come from farming tools (machetes) and street fighting weapons (blades and razors).

Mestre Bimba included in his teachings a ‘Curso de especialização’ (specialisation course). In the course, pupils would be taught defence against knives and guns, as well as the usage of the knife; straight razor; scythe; club; chanfolo (double-edged dagger); facão (machete) and tira-teima (cane sword).

This weapon training is almost completely absent in current capoeira teachings. However, some higher-ranked practitioners still practise weapons for ceremonial usage in the rodas.

The Game - ‘Playing’ Capoeira

‘Playing capoeira’ is both a game and a method of practising the application of capoeira movements in simulated combat. Although it can be played anywhere, it’s usually performed within a ‘Roda.’ The Roda is a circle formed by capoeiristas and capoeira musical instruments. Here every participant sings the typical songs and claps their hands following the music. The capoeiristas/players forming the body of the roda will be crouching down whereas the musicians are based at the ‘foot’ (pe’da) of the roda.

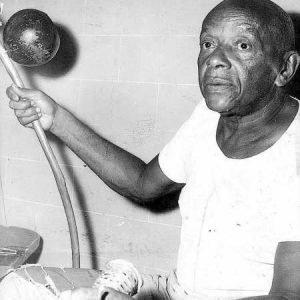

Even today, music and rhythm are integral parts of capoeira. They set the tempo and type of game that is to be played within the roda. Musical instruments set the tempo for the capoeira ‘sparring’ that is then played within the Roda. Two opponents will face each other within the Roda emulating in a stylised manner the strikes and parries of combat, in time with the rhythm of the music. The musicians will be playing traditional instruments associated with the practice. These include the berimbau; atabaque (congo), pandiero (tambourine), and agogo (bell). To the beat of the music, practitioners practise by chaining capoeira moves in an uninterrupted flow. Striking and evading without breaking motion.

Some of the musical instruments that can be found in Capoeira practice.

The Rhythm of the Fight

The capoeiristas change their playing style significantly following the ‘toque’ of the berimbau. A toque is an array of discrete rhythms the berimbau player generates using the instrument. The toque can dictate the pace, style and aggressiveness of the game. Whether the game is to be played fast or slow, depends upon the toques being played and the content of the lyrics.

No Capoeira practice is complete without the musical input of the berimbau and drums.

The musicians and/or players may be singing a song in Portuguese. The singing is sometimes in a call-and-answer format. Generally, the beginning of the song is done in narrative form, called ‘ladainha.’ Then comes the ‘Chula,’ or call-and-response pattern which may involve thanking God and one’s teacher. Corridos are songs sung while the capoeira game is being played after the call-and-response pattern.

The musical instruments used in Capoeira were also used to warn slaves/quilombos that the enemy was approaching.

Squaring off

Players enter the game from the pe’da roda (foot of the circle), usually with a cartwheel (au). Once in the circle, the two players interact with a series of moves. These will be a combination of jumps, kicks, flips, hand and headstands and other moves. Games can be friendly (slow) or dangerous (fast) depending on the skill levels of the participants. Capoeira is not a style that emphasises full body contact. Rather, when two practitioners square off, they often show moves without completing them.

During the ‘game’ most capoeira moves can be utilised. However, capoeiristas usually avoid using punches or elbow strikes (unless it’s a very aggressive game). The game usually does not focus on knocking down or destroying the opponent, rather it emphasises skill. Capoeiristas often prefer to rely on a takedown like a rasteira, before allowing the opponent to recover and get back into the game.

Capoeira practice takes place withing the ‘Roda’ a circle/semi-circle of players and musicians.

There is also a fair play aspect to the games. It’s very common for an advanced practitioner to slow down a kick inches before hitting a lesser-skilled opponent. Likewise, if an opponent cannot evade a more simplified or slower attack, a faster more complex one will not be utilised. This allows a capoeirista to display superiority without the need to injure the opponent.

However, between two high-skilled capoeiristas, the game can get much more aggressive and dangerous. Capoeiristas tend to avoid showing this kind of game in presentations or to the general public. The game will end when:

- One of the berimbau musicians determines it.

- When one of the capoeiristas decides to leave or call the end of the game.

- When another capoeirista interrupts the game to start playing, either with one of the current players or with another capoeirista

Ranking

Historically, there never really existed a ranking system accepted by most of the capoeira mestres until recently. However, some bodies and organisations have their own gradings depending on the group’s traditions. The most common modern system uses coloured ropes, called ‘Corda/cordão,’ which are tied around the waist.

Many capoeira bodies (leagues, federations and associations) have tried to unify the ranking system. The most well-known is that of the ‘Confederação Brasileira de Capoeira’ (Brazilian Capoeira Confederation). The Confederation adopted a grading system of ropes based on the colours of the Brazilian flag (green, yellow, blue and white). The various cords symbolise numerous ranks starting with beginner (iniciante) to mid-level (Professor) to master (Mestre).

However many other groups prefer to use different systems (for example; Porto da Barra Group which uses belts that tell the Brazilian slavery history). A number of groups (mainly of the Angola school) use no visible ranking system at all.

Sub Styles of Capoeira

Capoeira Angola

The oldest form of Capoeira, steeped in tradition. It is generally practised lower to the floor and practised slower than other styles. Capoeira de Angola refers to every capoeira that maintains traditions from before the creation of the regional style. Existing in many parts of Brazil since colonial times, most notably in the cities of Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Recife. In some parts of Brazil people refer to capoeira as ‘playing Angola.’ Capoeira Angola seeks to keep capoeira as close to its original roots as possible. It is characterised by being strategic and using deceptive movements. These are executed either standing or close to the floor depending on the situation at hand.

Capoeira Regional

This is the most common form of Capoeira. It is also generally the one people speak of when they are referring to ‘Capoeira’. Capoeira Regional began to take form in the 1920s. At this time, Mestre Bimba and student, José Cisnando Lima believed that capoeira was losing its martial side. They concluded there was a need to re-strengthen and structure it. Bimba’s reforms utilised original capoeira without many of the aspects that were impractical in a real fight. His new style contained less subterfuge and more objectivity. Training focuses mainly on attacking, evasion and counter-attacks. There is much emphasis on precision and discipline. The use of leaping or aerial acrobatics was reduced to a minimum. One of its foundations is always keeping at least one hand or foot firmly attached to the ground.

Capoeira Contemporânea

In the 1970s a hybrid style of capoeira emerged, with practitioners taking the aspects they considered more important from both Regional and Angola. Notably more acrobatic, this sub-style is seen by some as the natural evolution of capoeira. However others perceive the new style as an adulteration or even misinterpretation of capoeira. Nowadays the label ‘Contemporânea’ applies to any capoeira group who don’t follow Regional or Angola styles, even those who mix capoeira with other martial arts.

Several of the eight training sequences were developed by Mestre Bimba. Covering the basic fundamental moves of capoeira.

Street Effectiveness

Capoeira is a unique martial art that blends acrobatics, rhythm, and deception into its movements, making it unpredictable in a fight. The ability to use constant motion, feints, and evasive techniques can make a capoeirista a frustrating opponent, particularly against an untrained attacker. The emphasis on mobility means capoeira practitioners can avoid direct attacks rather than absorbing damage. However, its biggest weaknesses in a street fight come from its lack of emphasis on direct striking power, grappling control, and defensive positioning against multiple attackers or weapons. While it can be effective for evasion and surprising an opponent, it requires adaptation to be truly functional in an unpredictable street scenario.

Pros

✔ Highly evasive and unpredictable.

✔ Excellent mobility and agility.

✔ Strong sense of timing, rhythm, and deception.

✔ Can deliver powerful spinning kicks.

Cons

✘ Lack of emphasis on traditional guard and hand strikes.

✘ Few grappling or clinch-fighting techniques.

✘ Heavily reliant on space to manoeuvre.

✘ Some techniques are impractical for real fights.

Capoeira Today

Capoeira has grown tremendously over the last eighty years. In the 1970s, Capoeira mestres began to emigrate and teach it in other countries. Competitions and academies surfaced in many countries which have led to the creation of a national federation of Capoeira. Capoeira has been instrumental in highlighting Brazilian culture all over the world. Every year it attracts thousands of foreign students and tourists to Brazil. Additionally, many foreign Capoeiristas learn Portuguese to increase their understanding of the art.

In 2014 the Capoeira Circle was added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Finally recognised for its contribution to Brazil’s cultural heritage.

MMA

Many Brazilian MMA fighters have a Capoeira background, either training often or having tried it before. Some of them include Anderson Silva who trained in capoeira at a young age and as a UFC fighter; Thiago Santos, an active UFC middleweight contender who trained in capoeira for 8 years; Former UFC Heavyweight Champion Junior dos Santos, who trained in capoeira as a child and incorporates its kicking techniques and movement into his stand up. UFC veterans José Aldo and Andre Gusmão also use capoeira as their base. More recent fighters using the style include Michael Pereira whose flamboyant and unorthodox (to MMA at least) high-flying style has caught many of his opponents off guard.

Well-known capoeiristas in MMA include UFC Hall of Famer Anderson Silva (left) and up-and-coming fighter Micheal Pereira (right).

Summary

Capoeira appeals to people for many different reasons. Evolving from tribal dances and traditions out of Africa; developed by runaway slaves, fugitives, outlaws and streetfighters to combat their oppressors. It is more than just a combination of gymnastics, dance and martial arts. Tied in with the art is a history of pain, violence, traditions and liberation, music and culture, philosophy and knowledge. To watch capoeiristas at play is mesmerising, to take part is something special. The capoeirista must learn to balance the physical with the mental. It requires them to not only take part in capoeira practice but also to play instruments and sing. It is all of those things.

Or as one Capoeira Mestre Almir das Areias defined capoeira:

‘a fight, a dance, a form of personal defence, sport, culture, art and folklore, as well as music, poetry, celebration, amusement, recreation and, above all, a form of struggle, a public demonstration and expression of the people, the oppressed common man in general, who is in search of survival, freedom and dignity.’

If you have enjoyed this post please share or feel free to comment below 🙂

Related Posts

Our Other Posts