Boxing may have ancient roots, but it was in Britain that chaos was hammered into order. From bare-knuckle brawls to codified rules, Britain gave the sport its structure, discipline, and identity.

Table of Contents

🇬🇧 From Bloodsport to Blueprint

It was in 18th and 19th century Great Britain that boxing began to transition from mob entertainment to structured sport. While unarmed combat existed in many cultures, it was the British who took the raw brawls of the street and codified them into something recognisable, repeatable, and eventually respectable.

📜 Codification of Rules

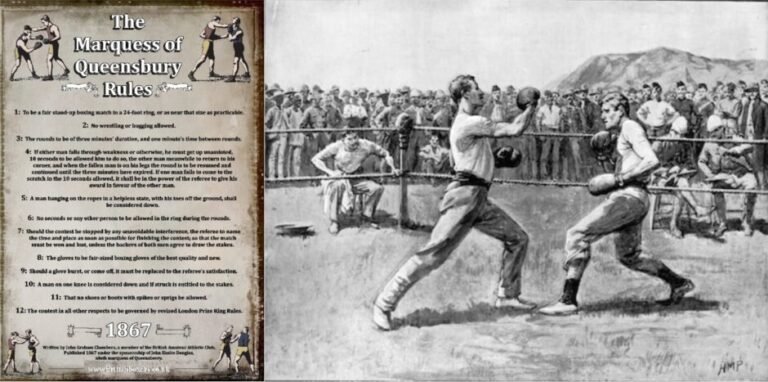

Boxing’s evolution from street fight to sport began in 18th-century Britain. What started as brutal street brawls slowly took shape through a series of rulebooks — from Jack Broughton’s code to the London Prize Ring and Queensberry Rules. Each step refined the sport, trading savagery for structure while still preserving its raw fighting spirit.

The Marquess of Queensberry Rules (1867) – the code that turned prizefighting into modern boxing, introducing gloves, timed rounds, and structured weight divisions.

Click the links below for more.

🥊 Jack Broughton and the First Rulebook (1743)

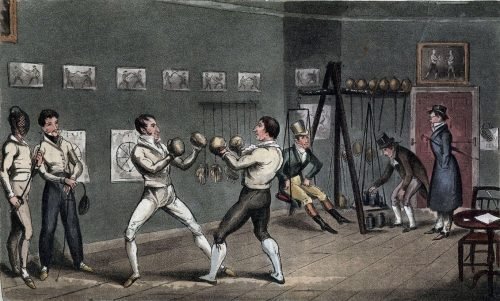

The first major step toward organised boxing came in 1743, when bare-knuckle champion Jack Broughton introduced a rule set to protect fighters and standardise contests. His code banned hitting a downed opponent and allowed rest breaks between rounds — small but crucial advances in fighter safety. Broughton also created padded training gloves, or “mufflers,” for sparring, planting the first seed of the modern gloved sport. His rules marked the beginning of boxing as a regulated discipline rather than a public brawl.

⚖️ The London Prize Ring Rules (1838–1853)

Nearly a century later, the London Prize Ring Rules built upon Broughton’s foundation. First published in 1838 and revised in 1853, they formalised ring dimensions, fouls, and recovery time after knockdowns. Bouts were still bare-knuckle and rough, with clinching and throws permitted, but these rules gave the sport consistency and legitimacy. For the first time, boxing had a universal code of conduct — an arena of honour rather than chaos.

🧤 The Marquess of Queensberry Rules (1867)

The game-changing moment came with the Marquess of Queensberry Rules in 1867. These rules are the cornerstone of modern boxing, mandating:

- Use of padded gloves.

- Three-minute rounds with one-minute rest.

- Ten-second count for knockouts.

- Prohibition of wrestling or throws.

- Creation of standardised weight classes.

These reforms turned boxing into a sport rather than a street fight. The gloves, in particular, allowed longer fights with more tactical striking, encouraging finesse over brute force.

By the late 19th century, boxing had achieved a delicate balance between savagery and sophistication. Britain had turned a violent pastime into a disciplined combat sport — a model soon emulated worldwide.

🥊 Boxing’s Class Crossover: From Taverns to Elite Schools

As rules brought order to the ring, boxing began to climb Britain’s social ladder. What started as a pastime of labourers and gamblers soon caught the attention of officers, nobles, and scholars. From smoky taverns to the halls of Eton, the sport evolved into both a working man’s battleground and a gentleman’s proving ground — a rare meeting point between class, courage, and culture.

By the late 1800s, boxing had left the taverns and entered the halls of Britain’s elite. Once a street brawl, it became a gentleman’s lesson in discipline, courage, and controlled aggression.

Click the links below for more.

👊🏻🍺 From Taverns to the Ring

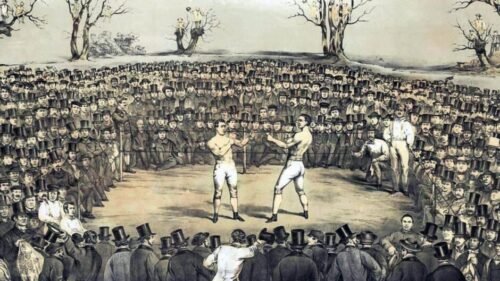

In its early days, British boxing was entrenched in the working class — a pastime of dockworkers, coal miners, and street brawlers. Matches took place behind pubs or in open fields, surrounded by gamblers and jeering crowds. It was rowdy, raw, and dangerous.

But as rulebooks brought order and consistency, boxing began to shed its outlaw image. The introduction of referees, gloves, and timed rounds made it more than a bloodsport — it became a test of toughness and technique. Aristocrats and officers began attending bouts, drawn to the sport’s discipline and spectacle — laying the groundwork for its rise into respectable circles.

👩🦰🥊 Women in the Prize Ring

Though often forgotten, women also fought bare-knuckle bouts in 18th- and 19th-century Britain. Fighters like Elizabeth Wilkinson, the “Female Bruiser,” drew crowds for their ferocity, taking on both men and women. While dismissed as novelties by polite society, their bouts proved boxing was never entirely male-dominated. They showed that courage and combat skill transcended gender long before women’s boxing was legitimised in the modern era.

🎩 Boxing in Britain’s Upper Institutions

By the late 1800s, boxing had reached Britain’s elite schools and military academies. Institutions like Eton, Harrow, and Sandhurst adopted the sport as a means of building courage, self-control, and leadership under pressure.

Here, boxing was reframed — not as survival, but as self-mastery. Students were taught respect, composure, and restraint through the discipline of the ring. Some schools even introduced uniforms and internal rules, turning the sport into part of a gentleman’s education.

This class crossover gave boxing a unique identity — one of the few sports where a nobleman and a street tough might share a ring. It also helped ensure boxing’s survival; with upper-class backing came political protection, media legitimacy, and broader social acceptance.

🥇 The Birth of Amateur Boxing

Boxing’s respectability was solidified with the founding of the Amateur Boxing Association (ABA) in 1880. The ABA’s first championships that same year introduced a world of non-professional, rules-based competition. Unlike prizefighting, which revolved around betting and spectacle, amateur contests valued sportsmanship, skill, and discipline. Britain became the first nation to formalise amateur boxing — a model later adopted worldwide and embedded in the Olympic movement.

By the close of the 19th century, boxing had achieved full social acceptance. Backed by elite schools and the ABA, it stood at the crossroads of grit and respectability — uniting miner and nobleman alike under a single code of honour and discipline.

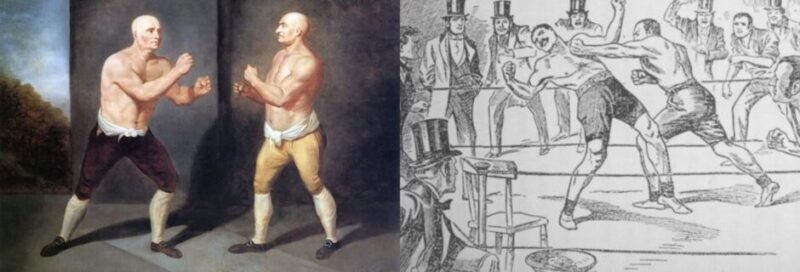

🇬🇧 Notable British Prizefighters of the Era

Long before championship belts and televised bouts, British prizefighters built their reputations through raw courage and public spectacle. These were men forged in an age when boxing meant blood, honour, and survival — shaping the sport’s identity and elevating it from street brawl to national tradition.

Jack Broughton (left) is remembered as the ‘Father of Boxing’ for codifying the first formal rules in 1743, protecting fighters and laying the foundation for the London Prize Ring Rules. Jem Mace (right), often called the first world champion, bridged the bare-knuckle and gloved eras—helping to popularise the Queensberry Rules and establish modern boxing.

Click the links below for more.

⚔️ James Figg (1684–1734) – The First Champion

Often called the first English bare-knuckle champion, Figg was a master of multiple fighting arts, including sword and cudgel combat. He ran a famed London academy that treated unarmed fighting as a disciplined craft rather than a brawl, setting boxing on its path toward legitimacy.

📜 Jack Broughton (c. 1703–1789) – The Father of Boxing Rules

A student of Figg, Broughton codified the first formal rules of boxing to reduce fatalities and fouls. He also introduced the concept of sparring with mufflers (primitive gloves) and promoted honourable conduct in combat, helping shift the sport’s reputation from blood sport to regulated contest.

🇬🇧 Tom Cribb (1781–1848) – The People’s Champion

A legendary bare-knuckle heavyweight, Cribb’s epic bouts with Tom Molineaux, a freed American slave, captured Britain’s imagination. Their clashes embodied not only boxing skill but also national pride and racial tension, symbolising a Britain wrestling with its own identity.

🦶 Jem Mace (1831–1910) – The Gentleman Boxer

A bridge between bare-knuckle and Queensberry eras, Mace was famed for his defensive genius, footwork, and timing—a strategist who embodied the art of “hit and don’t get hit.” His technical brilliance anticipated the cerebral style of later defensive greats.

🏆 Bob Fitzsimmons (1863–1917) – The Fighting Blacksmith

Born in Cornwall and raised in New Zealand, Fitzsimmons fought under the British flag and became the first three-division world champion. Known as The Fighting Blacksmith, he pioneered the solar plexus punch, combining precision, power, and tactical acumen. Fitzsimmons symbolised Britain’s evolution from brutal prizefights to global boxing mastery.

💢 Grudge Matches and National Rivalries

Many early prizefights were fuelled by personal grudges and national rivalry—none more famous than Cribb vs. Molineaux, a symbolic clash between race, class, and empire. These weren’t mere contests of strength but ritualised wars of identity, fought with fists instead of sabres.

Through their grit and character, these fighters laid the foundation for Britain’s boxing legacy. They embodied the nation’s toughness and pride, turning the prize ring into a stage for class struggle, national rivalry, and the timeless art of controlled violence.

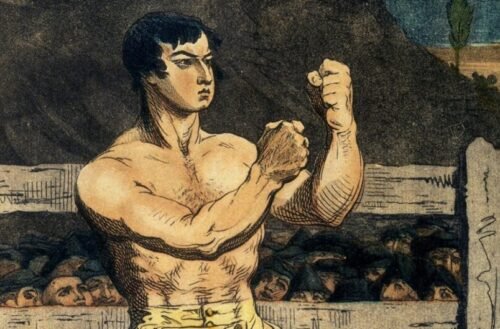

📐 Scientific Boxing – The British in Blueprint for Technical Combat

From Britain’s rough prizefighting roots emerged a new way to fight — one driven by technique, timing, and strategy. As boxing evolved from brawl to craft, a new generation studied movement, defence, and precision. At the forefront stood Daniel Mendoza, whose tactical genius transformed pugilism into a science and laid the foundation for what became known as Scientific Boxing.

Daniel Mendoza challenged the brutality of early boxing, proving skill and strategy could triumph over raw force and paving the way for ‘scientific’ boxing.

Click the links below for more.

🧠🥊 The Thinking Fighter: Mendoza’s Revolution

In the late 18th century, Daniel Mendoza (1764–1836), a Jewish prizefighter, redefined boxing. In an era ruled by brute force, Mendoza introduced head movement, counterpunching, footwork, and tactical defence. He proved that ring IQ and timing could defeat aggression, turning fights into battles of strategy rather than endurance. His manual on boxing helped formalise technique, while his rise to national fame transformed public perception — from street brawl to skilled combat.

Mendoza’s legacy extended beyond the ring. As a Jewish athlete in a prejudiced society, he symbolised resilience and social mobility, inspiring other marginalised fighters to see boxing as a path to respect. His influence marked the dawn of Scientific Boxing — a sport governed by discipline, not chaos.

🥊 Tactical Warfare Replaces Brutality

This shift wasn’t just linguistic; it marked a cultural evolution in the sport. With the Marquess of Queensberry Rules (1867) introducing gloves, timed rounds, and rest periods, fighters could now strategise rather than merely survive. Techniques such as angles, feints, and distance control began to dominate.

Across Britain, new boxing clubs emerged, providing structured training and discipline. Fighters were coached, conditioned, and mentally prepared — shifting from reckless trading to measured, tactical engagement. Trainers built a style founded on defence, timing, and composure, a system that would shape boxing’s global DNA.

📐 Key Elements of Scientific Boxing

- Footwork and angles – Fighters began to circle and pivot rather than march forward in straight lines.

- Defensive mastery – Parrying, slipping, ducking, and blocking became core parts of training.

- Feints and deception – The jab was used not just to hit but to test reactions and set traps.

- Distance control – Fighters learned how to fight “long,” picking their shots and avoiding damage.

🏛️ The Legacy of British Ringcraft

By the late 19th century, these tactical evolutions had reshaped the sport. British gyms became laboratories of movement and control, teaching fighters to think as well as strike. The blueprint forged by Mendoza and his successors echoed through generations, influencing fighters across the Atlantic and beyond.

Britain’s ringcraft became more than a fighting method — it was a philosophy. “Hit and don’t get hit” didn’t begin under Vegas lights; it was born in smoky London gyms where trainers honed fighters like blades, turning brawling into art. From Figg to Broughton to Mendoza, Britain forged the mind of the modern boxer — proving that precision and patience could triumph over brute force.

By the late 19th century, Britain’s Scientific Boxing style had become its hallmark — fought with savvy and cunning, rather than blind fury. From London’s boxing gyms to military halls, fighters learned precision and control. That mindset would soon define the rise of Britain’s great boxing schools.

🌍🚢 Cultural Export – Global Spread via Empire

Boxing’s rise in Britain didn’t stop at its shores. As the British Empire expanded, so did its version of organised pugilism. Soldiers, sailors, and settlers carried the sport across continents — from Indian garrisons to Australian ports — turning boxing into a global export of discipline, toughness, and identity.

The 1860 clash between England’s Tom Sayers and America’s John C. Heenan was hailed as the first true international boxing match. Brutal, chaotic, and fought to a draw, it marked the peak of Britain’s bare-knuckle era and set the stage for America’s growing influence on the sport.

Click the links below for more.

⚓ Empire Builders and the Spread of Boxing

As the Empire reached its height, rule-based boxing travelled with it. Colonies from India to Australia adopted the Queensberry format, laying the groundwork for boxing’s international footprint. British sailors and soldiers brought the sport to every port and outpost, teaching it as a test of resilience, self-defence, and character. What began as recreation soon became a mark of imperial toughness and unity.

🇺🇸 Across the Atlantic – Prizefighting Finds a New Home

As the Empire reached its height, rule-based boxing travelled with it. Colonies from India to Australia adopted the Queensberry format, laying the groundwork for boxing’s international footprint. British sailors and soldiers brought the sport to every port and outpost, teaching it as a test of resilience, self-defence, and character. What began as recreation soon became a mark of imperial toughness and unity.

🪖 Boxing in the Military and Colonial Culture

The British military made boxing part of its physical regimen, using it to build aggression, discipline, and composure under stress. Matches were staged across India, Africa, and the Caribbean, turning barracks and parade grounds into informal rings. Long before professional circuits, boxing had become a staple of colonial life, symbolising control, courage, and the British sense of order amid the Empire’s frontiers.

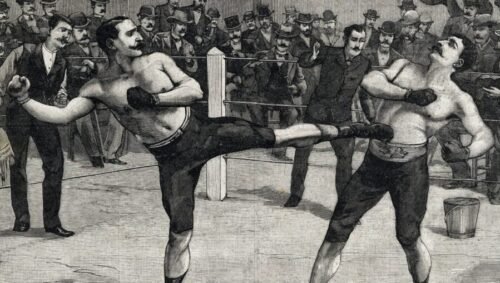

🇫🇷 Anglo-French Rivalry and the Rise of Savate

In 19th-century Europe, British boxers frequently clashed with French Savateurs, whose upright stance and kicking style contrasted sharply with Britain’s grounded punching. These cross-Channel duels — fought in clubs, exhibitions, and ports — were more than spectacles; they were technical exchanges that shaped European martial culture.

Over time, the French incorporated elements of English boxing into Savate’s striking arsenal, particularly its straight punches, defensive guard, and counterpunch timing. The result was Boxe Française Savate, a hybrid art that fused British punching precision with French footwork and flair. These early encounters didn’t just spread boxing’s influence — they helped redefine France’s own fighting identity, proving how one nation’s sport could evolve into another’s martial art.

🔄 Local Adaptations – Colonies Make Boxing Their Own

Colonial fighters didn’t merely imitate the British style — they transformed it. Caribbean boxers brought rhythm and looseness; Indian and African fighters emphasised timing and speed. One standout was Barbados Joe Walcott, a ferocious welterweight from British Barbados who became a world champion in the United States. His explosive approach embodied the new fighting DNA emerging from the colonies — proof that boxing was evolving into a truly global art.

🇫🇷 Anglo-French Rivalry – In the 19th century, British boxers often squared off against French Savateurs, showcasing contrasting styles: the raw, grounded puncher vs. the upright, kicking stylist. These public duels helped solidify boxing’s supremacy in the Anglo world while seeding its growth across Europe.

What began as a British pastime soon took root across the Empire, blending with local temperaments and traditions. These early exchanges forged boxing’s global identity — a sport reborn in new cultures, each adding its own rhythm, grit, and soul to the science of the ring.

🥊 The Rise of the British Boxing Gym

Boxing may have been codified in Britain, but it was inside the gyms and clubs where the sport truly came alive. From smoky backrooms to post-war civic halls, these spaces forged fighters, disciplined working-class youth, and gave the sport roots that ran far deeper than aristocratic patronage. The gym was where science met grit, and where the spirit of British boxing was truly born.

Britain’s oldest boxing clubs — Repton (1884) and Lynn AC (1892) in London — still shaping fighters the hard way. No glamour, no shortcuts, just sweat, blood, and the sound of the bell.

Click the links below for more.

🏭 Industrial Towns and Working-Class Clubs

By the early 20th century, Britain’s industrial cities pulsed with boxing energy. Makeshift rings filled pubs, fairgrounds, and working men’s clubs. For miners, dockers, and factory hands, boxing offered escape, honour, and identity — a chance to fight for both pride and livelihood. Local newspapers and radio brought these contests into homes, transforming working-class heroes into household names and community legends.

🏙️ Regional Styles and Pride

Every city built its own fight culture. London’s East End became known for slick, technical stylists — clever on defence and sharp with the jab. Liverpool earned fame for relentless, pressure-heavy fighters forged by dockside grit. Manchester balanced aggression with craft, producing boxers of equal flair and resilience. Scotland, too, produced iron-willed battlers from Glasgow and Edinburgh. These rivalries weren’t just regional bragging rights; they were laboratories of style that enriched British boxing’s diversity.

⚔️ War and the Boxing Boom

The World Wars brought boxing to the barracks. Soldiers trained in it for toughness and morale, staging bouts from the trenches to troopships. When they returned home, many founded local clubs or took up coaching, passing down discipline through generations. By the 1940s and 1950s, civic gyms linked to factories, unions, and councils had spread nationwide — rooting boxing deeply in Britain’s post-war identity.

📺 Television and the Golden Age of Clubs

With the rise of television, boxing entered the living room. Clubs like Repton (London) and Rotunda (Liverpool) became gateways to stardom, offering working-class youth structure, mentorship, and a shot at glory. The gym was both a sanctuary and a proving ground — a place to channel frustration into focus, and hardship into honour.

🔑 Legacy of the Gyms

These were no polished academies — they were crucibles of character. Beyond creating champions, they taught discipline, respect, and belonging. Britain’s gyms became the heartbeat of the sport, producing world-class fighters and keeping generations off the streets. The legacy of these clubs endures: proof that boxing’s true strength lies not in money or spectacle, but in the grit of its grassroots.

By the mid-20th century, the British boxing gym had become an institution. It produced not only world-class fighters but also generations of disciplined, resilient men shaped by routine, respect, and grit.

🥷 Going Underground – UK Boxing and the Underworld

Yet while boxing climbed the social ladder and gained respectability, another version refused to die. Beneath the polished world of sanctioned bouts and championship belts lay a parallel scene — the old spirit of the bare-knuckle world still breathed in cellars, pubs, and backyards. Driven by gambling, fixers, and criminal influence, underground fights and blood-soaked brawls carried on in defiance of the new order. Boxing’s roots in the shadows never vanished, the underworld remained the sport’s silent partner.

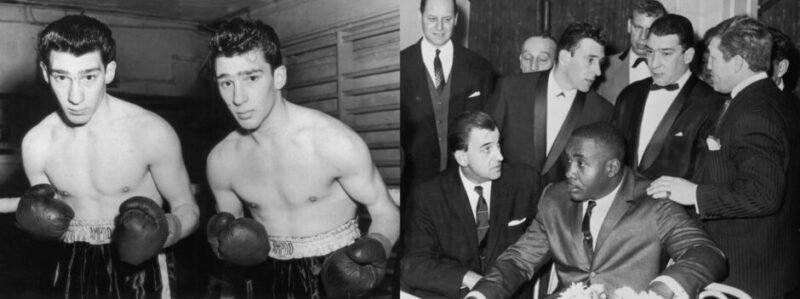

Twin brothers Ronnie and Reggie Kray were notorious London gangsters who ruled London’s East End in the 1950s and 1960s, mixing crime with celebrity. Their reach extended into boxing — managing fighters and fixing bouts to boost their power and influence.

Click the links below for more.

🥊 From Fields to Backrooms – Bare-Knuckle and the Fixers

Even as rules took hold and gloves replaced bare knuckles, echoes of the old world lingered. Prizefights in pubs and fields still ran on heavy betting — and corruption was inevitable. Local strongmen and fixers decided who fought, who won, and who got paid. For many working men, the ring offered escape from poverty — but the fight game was still ruled by the underworld’s hand.

🎲 Gambling and the Gentlemen’s Game

With the Queensberry Rules, boxing entered clubs and halls — yet gambling stayed its lifeblood. Bookmakers blurred the line between sport and business, fixing odds and outcomes. Respectable on the surface, the sport still carried the stink of backroom deals, where winners could be chosen long before the first bell.

🎟️ The Rise of the Promoter

By the late 1800s, legitimate promoters began imposing order. The National Sporting Club (NSC), founded in 1891, introduced referees, standardised titles, and formal championships. Hosting bouts in London’s Covent Garden, the NSC gave boxing prestige, enforcing rules and crowning recognised champions. For the first time, the sport looked both upward — to society — and inward, away from the mob.

🕴️🕴️The Kray Twins – Gangsters at Ringside

By the 1950s and ’60s, boxing’s criminal ties evolved with the Kray twins. Former amateur boxers turned crime bosses, they ran clubs, backed fighters, and turned ringside into a theatre of intimidation and glamour. For the Krays, boxing was never just entertainment — it was power, respectability, and control.

⚖️ Britain’s Shadow Game vs. America’s Mob Rule

Unlike the U.S., where Frankie Carbo and the mafia ruled the sport from the shadows, Britain’s underworld never fully seized control. Its influence came in waves — from fixers in the bare-knuckle days to gambling syndicates and gangland patrons. The result was a fight culture that always balanced legitimacy and the lure of the streets.

Across centuries, British boxing has lived between order and outlaw. Its ties to the underworld — from bet-rigging and shady promoters to the Kray empire — gave it both danger and allure. That shadow ensured boxing never lost its edge, grit, or connection to the streets that birthed it.

🏟️ Britain Today – Still a Boxing Hub

As the British Empire waned, boxing endured — one of its most lasting exports. Even as Britain’s global power faded, the sport it had codified continued to thrive at home and abroad, becoming a symbol of resilience and national pride.

The modern kings of British boxing — Calzaghe, Lewis, and Fury — proof that the Brits still have it.

Click the links below for more.

⚔️ The Empire Strikes Back – Britain’s Modern Gladiators

Through the 20th century, Britain produced a steady line of world champions who carried its legacy into the modern era:

- Lennox Lewis – Heavyweight legend, undisputed champion, one of the best of all time.

- Joe Calzaghe – Retired undefeated, long-reigning super middleweight king.

- Ricky Hatton – Beloved Manchester brawler, known for pressure and body shots.

- Naseem Hamed – “Prince Naz,” flamboyant showman with devastating power and speed.

- Chris Eubank & Nigel Benn – Fierce rivals whose clashes defined British boxing in the 1990s.

- Henry Cooper – National hero who floored Muhammad Ali in 1963.

- Tyson Fury – The “Gypsy King,” who reclaimed heavyweight dominance with charisma, chaos, and grit.

🏹 The Next Generation – Britain’s Rising Contenders

Today, a new wave of British fighters is carrying that same fire into the modern era.

Josh Taylor, Sunny Edwards, Leigh Wood, Conor Benn, Caroline Dubois, and Ben Whittaker represent the sport’s next evolution.

They blend British ringcraft with global flair, proving that the island that once codified the sport still breeds champions for a worldwide stage.

🇬🇧 Echoes of the Empire – Britain’s Boxing Legacy

Today, Britain remains one of the world’s great boxing hubs. Cities like London, Manchester, Liverpool, Sheffield, and Glasgow host sold-out fight nights year-round. Promoters such as Eddie Hearn’s Matchroom and Frank Warren’s Queensberry Promotions stage world-title events from York Hall to Wembley Stadium, while Team GB’s amateur programme continues to produce Olympic medallists.

Britain may no longer own the sport it codified, but it remains a global powerhouse — a nation where boxing is woven into both working-class identity and mainstream sporting culture. From backstreet gyms to world arenas, the spirit of British ringcraft endures — disciplined, defiant, and forever fighting its corner.

Three centuries on, the fight still echoes — not in taverns or colonies, but in gyms and arenas that carry Britain’s blueprint to the world.

🥊 What Britain Brought to Boxing

🇬🇧 Codified Rules – From Broughton’s early rule set to the London Prize Ring and Queensberry Rules, Britain gave boxing a structured framework.

🇬🇧 Gloves and Rounds – Introduced padded gloves, timed rounds, and rest periods—essential for turning brawls into strategic contests.

🇬🇧 Scientific Boxing – Pioneered a technical, cerebral style of fighting built on movement, defence, timing, and ring IQ.

🇬🇧 Boxing Clubs & Coaching – Developed formal training environments where fighters were coached and conditioned.

🇬🇧 Class Crossover – Elevated boxing from working-class pit fights to gentleman’s sport, even reaching elite schools and military academies.

🇬🇧 Women in the Ring – Produced early female fighters such as Elizabeth Wilkinson, proving the sport was never entirely male-dominated.

🇬🇧 Amateur Pathway – Founded the Amateur Boxing Association (1880), making Britain the first nation to formalise amateur competition.

🇬🇧 Global Spread via Empire – Exported boxing to colonies across the globe through military, maritime, and cultural influence.

🇬🇧 Promoters & Institutions – The National Sporting Club and others professionalised the sport, creating titles, referees, and fair governance.

🇬🇧 Regional Fight Cultures – Fight cities like London, Liverpool, Manchester, and Glasgow forged distinct identities and fierce rivalries.

🇬🇧 Cultural Respectability – Helped legitimise boxing in the eyes of the public and media, paving the way for mainstream acceptance.

🇬🇧 Legendary Fighters – Produced iconic early champions like James Figg, Jack Broughton, Tom Cribb, Jem Mace, and Daniel Mendoza—each shaping the sport’s early identity.

🇬🇧 Modern Champions – Delivered modern icons such as Lennox Lewis, Joe Calzaghe, Ricky Hatton, Henry Cooper, Naseem Hamed, Chris Eubank, and Nigel Benn.

🇬🇧 Boxing Hub Today – Still a global capital for the sport, with thriving gyms, major promoters, sold-out arenas, and a medal-winning amateur system.

From grimy London alleys to colonial outposts around the world, British boxing laid the groundwork for the sport’s transformation. Boxing wasn’t just about fists anymore—it was about form, rules, identity, and respect.

If you have enjoyed this post please share or feel free to comment below 🙂

Related Posts

Other Posts